Manuel "Cowboy" Donley: Originator of Austin's Modern Tejano Music Scene

Evaliza Fuentes

Texas-Mexican music is a direct descendant of Spanish and Mexican music while also being a distinct regional form. Contemporary performances by tejano artists include electric instruments and reflect advances in audio technology. Yet, before the integration of amplification, artists performed música tejana with acoustic instruments.1 The first tejano musicians and ensembles to “go electric” originated a new music scene and altered the sound experience of their audiences.

This new scene developed after World War II as other music genres in the United States experienced similar sonic changes. Amplification moved the big band genre into rhythm and blues, while country music’s Western swing evolved into honky-tonk. The electric transformation of the guitar and bass fiddle into amplified instruments capable of producing augmented volume makes the electric guitar and bass mechanically separate from its acoustic equivalents.2 The expanded sound carried by electric guitar amplifiers along with the use of microphones meant that large ensembles of nine to twelve members could be brought down to six to eight. The youth of the 1950s witnessed these collective transformations and actively altered the dynamics of popular culture at a fundamental level. A generational shift occurred, and dated trends and practitioners became old-fashioned. Rock and roll, electric guitars, and youth symbolized the modern.

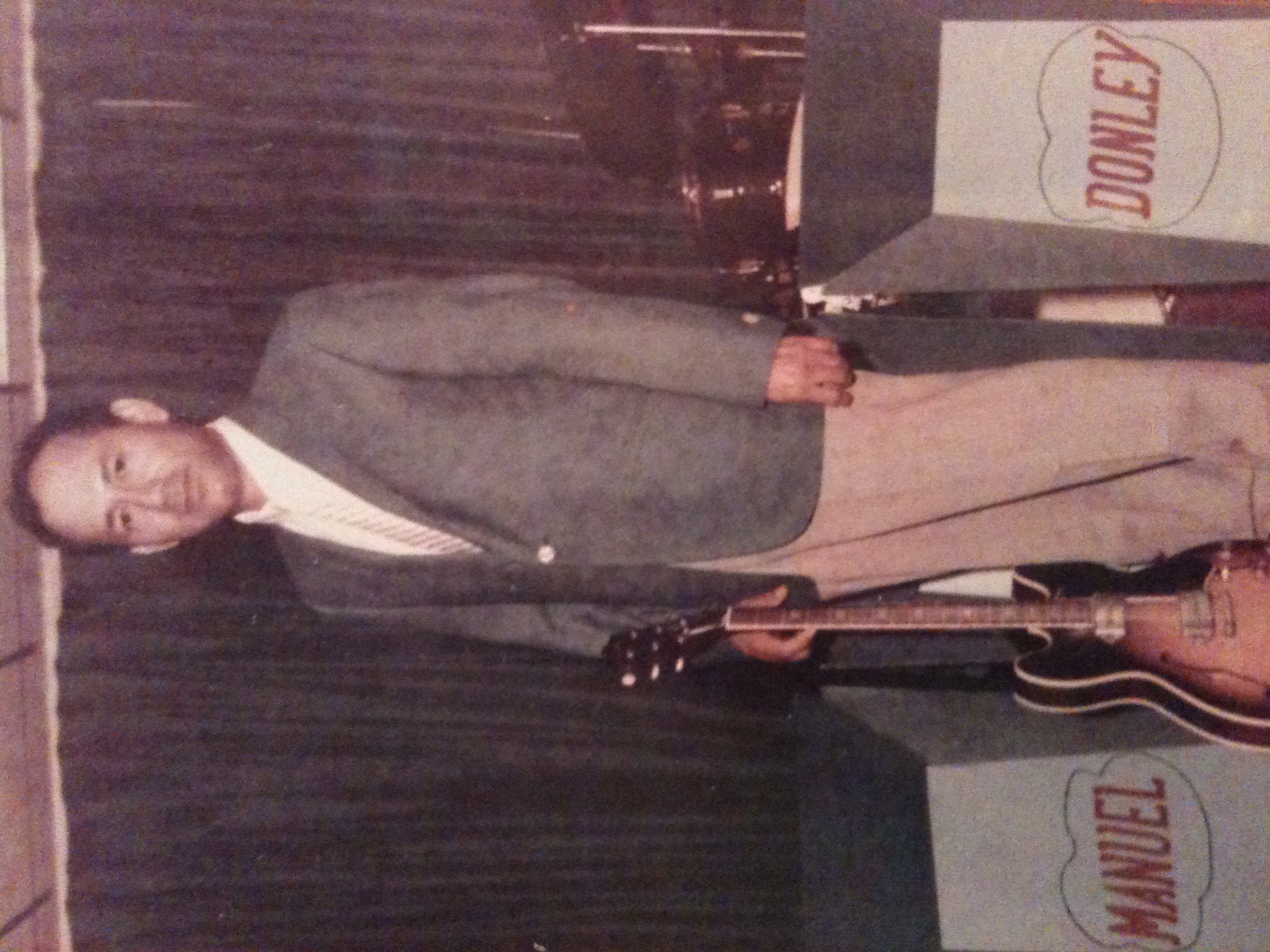

Manuel “Cowboy” Donley is a trailblazer in tejano music who represents this moment of transition. As the arranger, guitarist, and lead vocalist for Las Estrellas, Donley transformed música tejana from a traditional acoustic sound into the modern electric sound that dominates tejano music today. As a 2014 recipient of a National Endowment for the Arts National Heritage Fellowship, the NEA recognized Donley for his contributions to the ethnic American musical tradition of orquesta tejana. According to Donley, the modern tejano sound experience is electric, loud, amplified, energetic, confident, and bilingual, and he asserts that these sonic markers are a direct influence from rock and roll. Donley explains the effect on orquesta tejana: “A new sound . . . just the guitar with vocalist and lead on the guitar, you know. . . . They considered me a monster.”3 In Donley, tejano music welcomed its first electric guitar hero.4

Donley’s use of the word “modern” for the change in sound experience from acoustic to electric provides another perspective to the current scholarship that describes “modern” orquestas tejanas in terms of performing a bimusical repertoire that combines Anglo-American and Mexican-American musical cultures. The modern sound of música tejana is fundamentally electric guitar, electric bass, and loud drums. Donley used these instruments along with the alto saxophone, tenor saxophone, and trumpet when he established his amplified orquesta tejana Las Estrellas in 1955 and created a sound distinct from his acoustic predecessors.

This period of transition in the orquesta tejana ensemble from acoustic to electric prior to the introduction of the electric organ represents a lacuna in the existing historical narrative that merits attention and research to credit the groundbreaking efforts of Donley and his contemporaries. Currently, the popular discourse regarding the “pioneers” of modern tejano music begins with the 1960s and fails to account for the contributions of musicians in the 1950s. In academic circles, the impacts on música tejana of the electric guitar and electric bass as well as the popularity of rock and roll hits such as “Rock Around the Clock,” “Maybellene,” and “La Bamba” have yet to be fully uncovered. This gap in scholarship stands in stark contrast to the exhaustive treatment of the electrification of guitar in blues, country, and rock and roll. Tejano music, like other ethnic music such as bluegrass, jazz, and blues, merits closer examination through its central position in the Texas music narrative and, by extension, the regional music of the Southwest and the national music of the United States.

Through the incorporation of electrified instruments, música tejana embarked on a progression that parallels developments in Anglo- and African-American popular music. Amplification produced a sonic distinction and separated the ensemble instrumentation into the categories of modern electric and traditional acoustic. Manuel “Cowboy” Donley introduced the electric sound to the música tejana scene in Austin, Texas, in 1955, and his musical advances and extensive musical legacy assist in establishing a new narrative of the modern electric tejano scene’s origins and its accompanying cultural phenomenon in the 1950s.

Donley’s story also underscores Central Texas as a major player in a conversation that has often focused on San Antonio, Corpus Christi, and the Rio Grande Valley. The Austin urban area supplies música tejana with creators such as guitarist and band leader Manuel “Cowboy” Donley and producers such as Ben Moncivais of Valmon Records. Little Joe Hernandez, the multi-Grammy-winning orquesta tejana icon from Temple, Texas, says of Donley, “He certainly was one of my musical heroes.”5 Performing artists from metropolitan areas of Texas such as Austin, along with the associated music industry, must be represented within the tejano music narrative.

In 1955 when Donley electrifies música tejana, the switch reverberates throughout the entire genre in a revolutionary shift away from soft ballroom instrumentals to loud popular narrative music. This transition marks a milestone in the development and progression of música tejana, and at its center is Donley, a twenty-seven-year-old guitarist directly influenced by country music and rock and roll. As a product of the Austin tricultural soundscape, a bilingual Donley creates musical innovations within his Mexican-American bicultural identity in response to his lived experiences. In addition, he seized the rock and roll music of a generation in their teens and twenties and fused that electric and sonic energy with música tejana. This new, original sound laid the foundation for the contemporary scene.

A Sound Influenced by the Austin Soundscape

Donley is a cultural product of his geography, and his musical style reflects his lived experience. His family heritage is Tejano-Irish on his father’s side and Mexican national on his mother’s side.6 With his family’s arrival in Austin during his childhood, he became bilingual and bicultural, a resident of Mexico de Afuera.7 As a first-generation Mexican American growing up in East Austin, his Mexican-American neighborhoods bordered African-American neighborhoods.

Manuel Peña, in The Mexican American Orquesta, uses biculturalism to refer to a synthesis of two cultures, American and Mexican, including “the most dynamic of all bicultural practices—bilingualism and bimusicality.”8 This concept has relevance for the experience of many Mexican Americans. Yet, Yolanda Broyles-Gonzalez's discussion of cross-cultural musical bonding and interethnic musical conversations may be a better fit for the Mexican-American population in Austin in the 1950s. Broyles-Gonzalez describes how “musical languages have frequently crisscrossed cultural, ethnic, class, and supposed national borders—a testimony both to the lived proximity of diverse cultures and to the transgressive magnetism of musical cultures across social boundaries of class, ethnicity, gender, sexuality, and georegion.”9 Another explanation that is inclusive of the African-American cultural influences of a city like Austin on the music of a Mexican American like Donley is Jose B. Cuellar's concept of transculturation as “the complex combination of synchronizing and synthesizing processes that adopt and adapt, meld and blend, combine and fuse diverse cultural elements into somewhat new cultural expressions in innovative and inventive ways.”10

The radio airwaves of Austin in the 1950s predominantly offered English-language programming, but Spanish-language broadcasting was also available on KTXN 1370 AM. Both radio and television broadcasted a tricultural mix of Anglo- and African-American with Mexican-Latin music. The cross-cultural Austin soundscape influenced Donley’s guitar sound, and his position as a guitar-playing bandleader meant that he stood out in an orquesta scene where other band leaders such as Balde Gonzalez, Beto Villa, Isidro Lopez, and Oscar Martinez played saxophone, clarinet, or trumpet.11

Anglo Cowboys, Mexican Cowboys, “Cowboy” Donley

How did Manuel Donley come to be called “Cowboy,” and what might the moniker tell us about mid-twentieth-century Texas? On the most basic level, the ranching and agrarian life in Texas links Anglos and Mexicans. Donley was raised in an urban area with strong connections to nearby rural spaces. Both orquesta band leaders and conjunto accordion players recognized his skill as a guitarist. In Texas-Mexican Conjunto, Peña separates the Texas-Mexican conjunto ensemble from the orquesta by class divisions, citing perceptions that orquesta was more “sophisticated” and “high society.” With its use of bolero and danzón, orquesta developed middle-class connotations, while conjunto maintained its working-class identity with música ranchera (country music) expressing “the existence of hacienda and rural life.”12 Broyles-Gonzalez discusses música ranchera as songs that signify “that rural place of origin, known as ‘el rancho,’ where we lived before we moved to the cities and where the people can trace their deepest roots: the land.” In that geographic space, communities were bound together by the subsistence farming of corn, squash, and beans and life in little houses.13

Yet, I extend that the “rancho” is not just a sociocultural origin but a life that is indivisible from music. Ranch living connects to lifecycle rituals built on a soundscape that accompanies birth, adolescence, courtship, marriage, and death. Birth has the mañanitas (morning songs). Courtship has serenatas (serenades), and death has la despedida (goodbye song).14 The songs of this life are not just rancheras (country songs); they are also romanticas (romantic songs). Even the most masculine of caballeros (horsemen) can get lonely on a self-sustained ranch, and their thoughts will turn to love and companionship. The archetype of “El Caballero” of knightly legend who protects his home, his family, and his community and falls in love with a beautiful dama (maiden) encompasses the themes of both ranchera and romantica.

So, the music of Donley’s youth combines the ranchera and romantica under the larger archetypes of “El Músico” (The Musician) and “El Caballero” within “The Hero” subtype of “El Charro Cantor” (The Singing Charro) represented in Mexico by Jorge Negrete and Pedro Infante and in the United States under the hero archetype of the “Singing Cowboy” represented by Gene Autry and Roy Rogers. A charro (Mexican horseman) differs from a cowboy in the charro’s participation in the charrería, the equestrian sports of Mexico upon which the North American rodeo is built.15 The film careers of these men represented a parallel cultural iconography that was available to Donley in two languages. The popularity of their films made movie stars of Negrete, Infante, Autry, and Rogers. Relevant to Donley’s formative years are Infante’s Los Tres García (The Three Garcías) in 1946 in which he sings a version of “Cielito Lindo” (“Lovely Piece of Heaven”), followed by Negrete in 1948 with Allá en El Rancho Grande (Out on the Big Ranch) with a performance of the song of the same name.16 The compelling similarities of ranch life brought the Spanish “Cielito Lindo”17 and “Allá en el Rancho Grande”18 into the singing cowboy repertoire as documented in Songs of the Wild West and For a Cowboy Has to Sing, respectively. Three of Autry’s films, Rancho Grande (1940), Down Mexico Way (1941), and The Big Sombrero (1949)19 have relevance with their inclusion of Mexican tunes and English versions of the Mexican boleros “Solamente Una Vez” (“You Belong to my Heart”) and “Maria Elena.”20 Rogers’s film Song of Texas features “Cielito Lindo” among other Western standards such as “Mexicali Rose.”21

Donley shared his own boyhood memories of these film stars and his desire to learn to play guitar: “Of course, I love cowboys, you know. I’d go to the movies…Cowboys were my heroes, you know…and I start playing the guitar…because I love cowboys and they would always have a guitar and sing to a señorita…Then I started playing the guitar and attracting girls.” When asked to remember a song that one of those cowboys would sing to a señorita (a single young woman), Donley started strumming and singing, “Deep within my heart lies a melody, a song of ole San Antone…rose of San Antone.” He continued, “I used to love country music…and I have the guitar and ‘Hey, leave that thing at home.’ Oh no, I love to carry the guitar around. I was about fourteen or fifteen and I start singing. They start ‘postero,’ cedar chopper, you know, postero, hillbilly, all kinds of different names, you know, but heck I didn’t care. I loved the guitar and songs.”22 I am not sure how many famous singing cowboys sang “San Antonio Rose” when it became popular, but what is certain is that Bob Wills and his Texas Playboys became “national figures in American music” in 1940 (Donley would have been twelve) when their recording of “New San Antonio Rose” received a gold record and their style began to be called Western swing.23

The story of how a teenage Donley received his moniker “Cowboy” makes perfect sense because none other than a singing cowboy would walk the streets of Austin with a guitar in hand:

I was standing in front of Cisco's bakery on 6th street with a guitar and Del Martinez came, “Manuel you turn right there,” and he said, “Cowboy” (in a loud voice) because of my guitar, you know. All the people looked around and the guy said, “Cowboy? Cowboy? Cowboy?” because of the guitar. You know Gene Autry, Roy Rogers and all that, they all had a guitar. And that was the beginning of the name “Cowboy” Donley, right there on 6th and Comal.24

Peña attributes the “rancheroization” of the orquestas in the late 1950s to Isidro Lopez, as he amplified the ranchero elements of orquesta in ways that aligned the genre with working-class conjunto. Likewise, I argue that Manuel Donley’s singing cowboy stage presence and caballero archetype superseded previous separations between working-class and middle-class and canciones rancheras and romanticas. Isidoro Lopez, a long-time Austin-area disc jockey, explained the moniker and change in music scene in a 1998 article:

You cannot underestimate what that did. That [performance] style made it more loose, made [Las Estrellas] more accessible to the public. It also helped break down the stereotype of orquesta music being rigid. You have to remember, we were all working people, blue collar workers—it was a question of attitude and perception.25

The Tejano community of Austin embraced “Cowboy” Donley through the undeniable mass appeal of the troubadour who tells his tales of home and love through song in dancehalls, bars, and ballrooms. Today, ranching traditions and cowboy images continue as a source of creativity in música tejana.

Manuel “Cowboy” Donley – “The Hottest Guitar in Texas”26

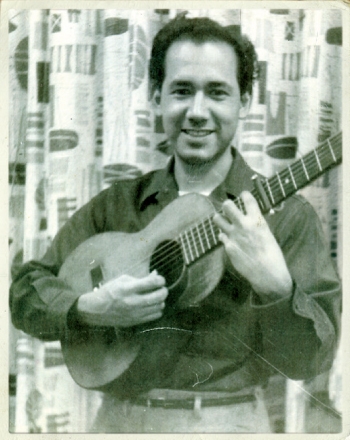

Donley was born in Durango, Mexico, in 1928, and moved to Austin with his family when he was seven. His father, Ramón Donley, had a musical career in Mexico as a violinist with the Durango municipal symphony. In Austin, his father was a barber and a musician.27 His mother, Dolores Quiñones, loved opera, and her sister performed it.28 By age eleven, he had taught himself to play the classical guitar29 and then later the requinto, a guitar tuned a fourth higher than a standard guitar and invented by Alfredo Gil of trio Los Panchos for use in introductions and interludes as a lead instrument in a bolero trio ensemble.30 Church festivals and street fairs were his performance venues with his brother Robert when he was seventeen.31

The bolero trio genre is of particular interest to this study, with Donley’s primary instrument in his formative guitar stage being the requinto. He also credits the early development of his requinto guitar stylings to the mentorship of the members of Trio Latino that included Tomás Rivera, Ike Puente, and Trini Estrada.32 This group mostly covered songs by trio Los Panchos, a bolero trio formed in 1944 in New York City by Mexicans Jesús “Chucho” Navarro and Alfredo “Güero” Gil, and Puerto Rican Hernando Avilés.33 Yolanda Moreno Rivas recognizes the profound impact of Los Panchos: “El año 1948 marco la aparicion de Los Panchos y el principio del apogee de los trios. El predominio de las suaves voces masculinas, las guitarras y el inflatable requinto creo un nuevo tipo de bolero y de cancion romantica (The year 1948 marked the appearance of Los Panchos and the beginning of the rise of the trios. The prevalence of soft masculine voices, the guitars, and the inflatable requinto created a new type of bolero and romantic song).”34

In 1949, Donley formed Los Heartbreakers and performed mostly instrumentals until a gig at Parque Zaragoza in Austin. A reluctant Donley sang “La Mucura” (“The Earthenware Jar”), a popular Colombian cumbia, for a demanding crowd. He shared with Juan Castillo, “There I became famous, but I never wanted to be a vocalist. The guitar, that was my passion.”35 In his text La Canción Mexicana, Vicente Mendoza remarks that “el instrumento favorito para el acompañamiento de la cancion es la guitarra y así debió de ser desde los principios (The favorite instrument for the accompaniment of the song is the guitar and it has been that way since the beginning).”36 After Donley’s breakthrough performance, he played with as many bands as he could while still being available for Los Heartbreakers.37 He could be found sitting in with the Ruben Perez orquesta, Conjunto Cielito Lindo, and the Brazos Bar musicians.38 It was during this time that Donley “bought an old pick-up in a second hand shop and put it on acoustic guitar and made it electric.”39 His association with a variety of ensembles reveals Donley's enthusiasm for his instrument and eagerness to advance his musicianship. Donley attributes his decision to switch to electric guitar to his skill on the requinto and the opportunity to display his flair: “No one else could do all the pickin’. They would strum.”40 In addition, this genre diversity demonstrates that he was performing outside the socio-economic class distinctions of middle-class orquesta and working-class conjunto theorized by Peña.

According to Sarah Wimer, Donley “made his first electric guitar using a single-edge razor to carve the body and attaching the fret board from a broken instrument.”41 While not an exact match to Les Paul’s story behind the creation of his electric guitar, “the Log,” which was made of a four-inch by four-inch strip of wood, an Epiphone guitar neck, and pickups, both stories demonstrate a capacity on the part of the musician for “do-it-yourself” construction.42 When asked why he constructed his first electric guitar, Donley’s response was economic in nature: “Because Fender guitars started at $300.”43

Donley was also passionate about rock and roll, citing Fats Domino, Little Richard, Bo Diddley, and Chuck Berry as his favorites.44 Fats Domino appeared on the pop chart in 1952, and by late 1956 “Blueberry Hill” climbed to number two. Domino recorded his own songs and arranged pop, big band, and country standards into his style.45 Donley made his own musical arrangement of “Blueberry Hill” for live performances.46 In 1955, Bo Diddley featured the syncopated percussive rhythm known as the “hambone” rhythm in his song “Bo Diddley,” and Little Richard recorded “Tutti Frutti,” which entered the charts by the end of the year. Chuck Berry's “Maybellene” became a number one hit on the rhythm and blues chart and number five on the pop chart in 1955. Berry authored songs for teenagers with stories of school, automobiles, and love, and his electric guitar solos set a new standard for all who came after him.47 In the 1950s, young people were drawn to musical groups that spoke to their high school experiences, and they developed an intimate bond with the music.48 Donley also enjoyed Bill Haley and Larry Williams, and popular songs like “C. C. Rider” and “Mop Rag Boogie.”49 Bill Haley's “Rock Around the Clock” in 1955 was the first rock and roll song to reach number one on the pop chart, which marks a pivotal moment for rock and roll entering the mainstream. He also had five songs on the rhythm and blues chart, which supports the view that rock and roll as a genre broke down social barriers during the 1950s.50 Donley’s love for these early rock and roll records and the influence of the resulting youth culture were timely in the establishment of his own orquesta.

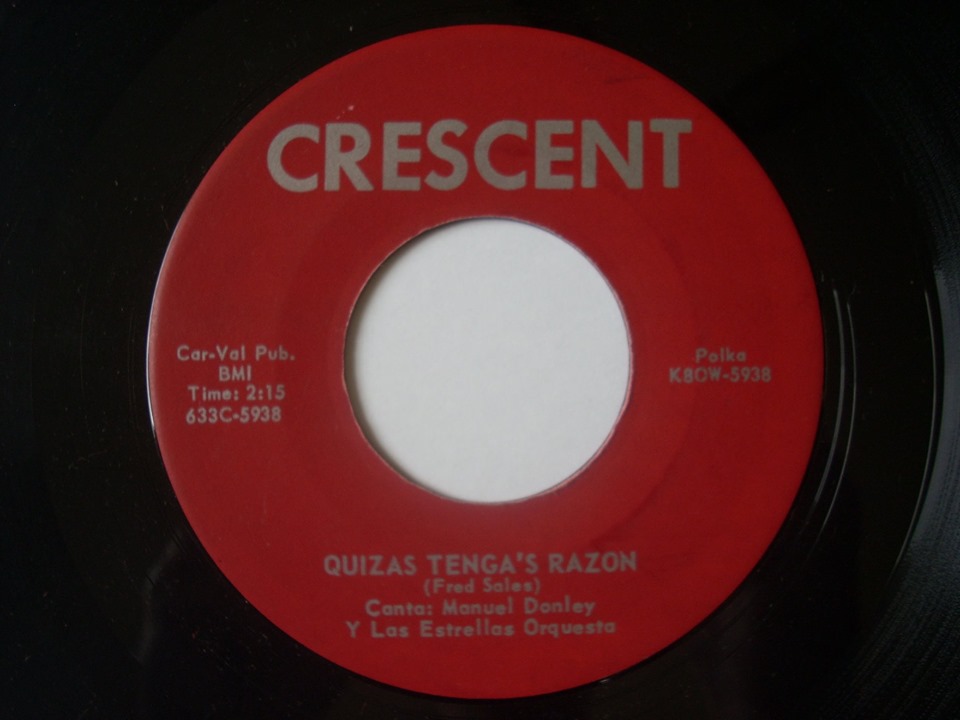

On Friday, May 15, 1959, Austin’s new Crescent record label debuted their first recording with Donley and billed him as “The Hottest Guitar in Texas.” With this advertised proclamation, Donley emerged onto the Texas music scene as an artist to watch. The record release party, which offered one free record to the first one-hundred girls at City Coliseum, was titled “PAN AMERICAN FIESTA-DANCE AND FROLIC.” Donley and Las Estrellas were promoted as “2 BANDS IN ONE, Playing Rhumbas, Mambos, Cha Cha Cha, and a Long Selection of ROCK AND ROLL.”51 The advertisement also includes the address for Car-Val Studios as 906 1/2 Congress Avenue along with ticket information.

Donley made the Crescent recording for Irene Couravallos, who owned the studio on Congress Avenue. According to Donley, she contacted representatives from New York, and they brought the sound recording equipment necessary to create 45 rpm records. She is listed as the songwriter for the bolero cha cha “Lluvia en Mi Corazon” (“Rain in My Heart”), which is backed with the polka “Quizas Tengas Razon” (“Maybe You’re Right”), written by Fred Salas. The label also designates the publisher as Car-Val Pub.52 However, the Crescent recording was not Donley’s first experience in a studio. In 1953, he recorded “Conjunto Cielito Lindo,” which consisted of Julio Ramirez on accordion, the Flores brothers—Cresencio “Chencho” on guitar and Frank on bajo sexto, Gaitano Rodriguez on upright bass, and Donley on requinto. They traveled to San Antonio for a session with Manuel Rangel, Sr. at Corona Records.53

Establishing Las Estrellas and the Creation of a New Music Scene

English literary critic Raymond Williams offers a useful model for thinking through historical shifts in music genres as cultural formations, as he argues that any cultural moment witnesses an overlapping of dominant, residual, and emergent forms. The residual elements of culture contain characteristics of the past, while the dominant maintains the present, and the emergent puts forth new ideas.54 This framework can be applied to música tejana, our discussion of the orquesta ensembles, and the accompanying stylistic changes introduced by Donley. The orquestas tejanas were products of their post-World War II time and emerged to replace the dominant orquestas típicas of the late 1930s and early 1940s. This tejano form of the orquesta then dominated the scene and influenced música tejana, leaving the orquesta típica in the residual past. Then in 1955 with the introduction of the electric guitar—Donley’s moment—the modern electric orquesta emerges. As the modern electric sound rises to the dominant culture, the traditional acoustic orquesta falls into the residual space. This process of recognizing cultural moments as dominant, residual, and emergent forms disrupts the periodization that dominates the literature on Texas Mexican music, most notably the works of Manuel Peña and Guadalupe San Miguel. In Tejano Proud, San Miguel identifies two eras during our period of study as “Post-World War II Developments, 1946-64” and “Before the Arrival of the Major Record Labels, 1964-89.” Following the Williams model, Donley and his contemporaries who originate the modern electric sound constitute a distinct era, a period from 1955 to 1964 during which they emerged onto the music scene and dominated the sound while acoustic orquestas drifted into the residual past. The next newcomers, Little Joe and Sunny Ozuna, with their tejano music market breakout hits “Por Un Amor” (“Because of a Love”) and “Cariño Nuevo” (“New Sweet Love”) in 1964, respectively, appeared on the scene and initiated the decline of the 1950s originator groups. Little Joe’s biggest hit “Las Nubes” (“The Clouds”) in 197255 marks his supremacy until 1977 when Mazz emerged with the release of their first album with Cara Records.56 So, I propose that the two periodizations, 1946-64 and 1964-89, should be expanded to four, 1946-55, 1955-64, 1964-77, and 1977-89, which more accurately reflect cultural developments and musical innovations while making space for the trailblazing efforts of the modern electric groups from the 1950s.

Throughout the late 1940s and early 1950s, Austin had multiple orquestas tejanas that reproduced a big band sound with a soft rhythm section and acoustic string instruments. These orquestas included the E.R. Flores Orquesta, Ruben Perez Orquesta, Laurence Salas Orquesta, Nemecio Carmona Orquesta, Chano Carmona’s Orquesta Caribe (Caribbean Orchestra), Catarino Rios Orquesta, Matias Velasquez Orquesta, and Nash Hernandez Orquesta. Most of these orquestas used stock big band arrangements or traveled to the Acosta Music Company in San Antonio to purchase popular sheet music performed by orchestras in Mexico.57

In photos from the Texas Music Museum, both guitarist Donley and drummer Emilio Villegas (with a drum set including bass, snare, high hat, cymbal, and possibly toms or bongos) are members of the Ruben Perez orquesta in 1953. The picture shows one microphone and additional band members in the back row, including Andrew Cantu (trumpet), Manuel Espinosa (trumpet), Mike Espinosa (stand-up bass) and in the front row, Manuel Sifuentes (sax), Ruben Perez (sax), Ernest Perez (sax), and Carmen Perez (maracas and vocal). Donley is also pictured as a guitarist with the Carmona Orquesta (with one microphone) whose band members include Salvadore Reyna, E.R. Flores, Victor Lozano (all on trumpet), Chris Carmona, Chano Carmona, Nemecio Carmona (all on sax), with Macario Carmona (bass drum, snare, possibly more), Albert Amezquita (piano), and Mike Carmona (unable to determine).58 Donley and Villegas as members of orquestas tejanas were participants in the acoustic orquesta music scene and not only witnessed the transformation into the electric era but were instrumental in the creation of a new ensemble style: orquesta amplificada.

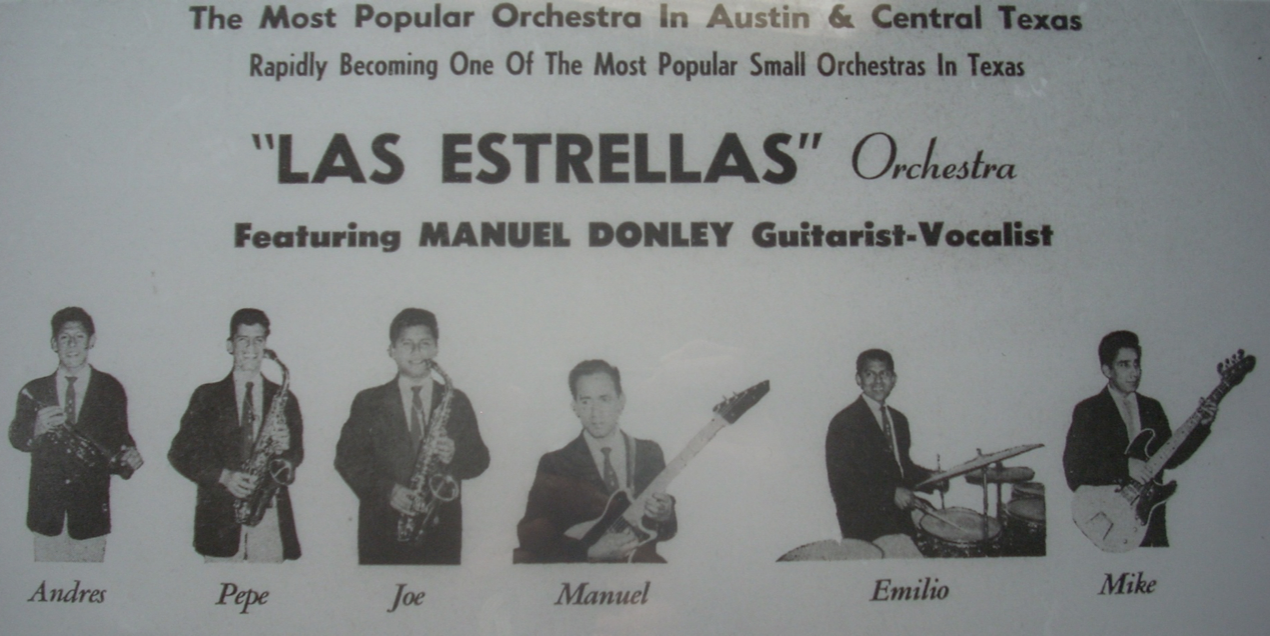

In 1955, Donley formed his own orquesta, Las Estrellas, driven by his new electric guitar sound. The self-taught guitarist also studied music theory and wrote most of the group’s musical arrangements. The original Las Estrellas were Rudy Sanchez (tenor sax), Joe Sanchez (alto sax), Andrew Zuniga (trumpet), Emilio Villegas (drum set), and Mike Amaro (electric bass).59 They were also self-taught and knew how to read music. The musical knowledge of the group allowed Donley to create expressive horn and saxophone arrangements for traditional Mexican rancheras, polkas, boleros, and ballads using American influences from big band, rock and roll, and rhythm and blues.60 Donley also changed the instrumentation of orquesta by “plugging his guitar into an amplifier, replacing the stand-up bass with an electric one and brush drums with drumsticks.”61

Donley’s ensemble followed San Miguel’s description of post-World War II orquesta tejana with its continuing reliance on the saxophone.62 However, Donley emphasized the amplified guitar and bass as the sonic markers that distinguished his group from the contemporaneous orquestas of Beto Villa and Isidro Lopez. The use of electric guitar in his own band was complemented by the incorporation of electric bass. Donley explains the stand-up bass “would not produce the clear note to make a harmony with the electric guitar.”63

According to Mike Amaro, a guitarist who first met Donley in 1945, Donley approached him about playing the upright bass for Las Estrellas, but without any knowledge of the upright bass, Amaro declined. Then Donley suggested he consider helping them out by purchasing an electric bass. Amaro agreed and went to J.R. Reed Music Company at 902 E. 5th Street, where he financed an electric bass and amplifier. Prior to joining Las Estrellas, Amaro had performed trio style with Donley for occasional gigs. In teaching himself the electric bass, Amaro applied his guitar knowledge, relating the four strings of the bass to the top four strings of the guitar. He explains, “So I just put it in my mind that I’m going to play it like it’s a guitar.”64 In discussing the function of the bass, Amaro shares that “the bass is driving the music . . . the dancers and all that.”65

Donley’s fans adopted the new loud, modern sound, and soon the group was in demand across Central Texas. As word spread, other bandleaders came to see Las Estrellas and incorporated Donley’s ideas into their own acts.66 Among these bandleaders were Manny Guerra from San Antonio and Johnny Canales from Corpus Christi.67 The band’s fame grew, and so did their tours of the state, from Dallas to the Rio Grande Valley. 68 Beto Villa himself even contracted Las Estrellas to perform for New Year’s Eve in 1958 and 1959 at the Beto Villa Ballroom in Falfurrias, Texas. As his musical career progressed, Donley eventually had youngsters such as Sunny Ozuna, Freddie Martinez, Juan Perez, Oscar Martinez, and Johnny Herrera as his opening acts.69

Mike Carmona, while not an original member of Las Estrellas, performed with Donley in the early years. As a music historian, Carmona affirms that Manuel “Cowboy” Donley and Las Estrellas revolutionized modern tejano music by shifting the orquesta tejana paradigm to a unified rhythm section built on the electric guitar, electric bass, and drums. Carmona also attributes the key elements of modern tejano music to Donley y Las Estrellas through the distinct guitar style of Donley, the shortened separated bass notes of Amaro, and the high-hat/snare combination of Emilio Villegas and positions this sonic arrangement years ahead of Little Joe y La Familia, the iconic orquesta tejana of the 1960s.70 In addition, Carmona extends Donley’s innovations beyond orquesta tejana to tejano music in general by differentiating multiple characteristics between his band and other contemporaneous groups. Beto Villa, Balde Gonzalez, and Isidro Lopez relied on fifteen to twenty members, the stage delivery of the big band era with musicians sitting down, long versions of instrumental tunes, predominantly ballroom dance rhythms such as danzón and waltz, and jazz compositions by Glenn Miller and Tommy Dorsey. Donley, however, featured six members, the stage delivery of country and western performers with musicians standing up, adaptations of popular music, predominantly social dance rhythms such as polka and bolero, and American rock and roll.71

When asked about the competition from other orquestas in Austin regarding Donley’s new sound and rhythm combination, long-time friend and former dance promoter Leon Hernandez emphasized the profound influence of Donley’s sound:

Everybody picked it up. All the bands. Fred Salas, I mean Laurence Salas, even the conjuntos that were around. The people that were playing in the bars, ‘cuz there was fifteen bars downtown, each one of them had a dance every Saturday night. They all had their bass guitars, their drums, guitar, and accordion and they all picked it up quick…Conjunto…didn’t have no drums, it didn’t have no guitar (electric), it only had the accordion, it didn’t have no bass. It was accordion, guitar and tololoche (stand-up bass) the three, that was a conjunto.72

In this account, Hernandez designates Donley as the originator of the modern electric tejano sound in Austin. The popularity of Donley’s amplification of the guitar and bass in combination with the drum set moved across the tejano music ensembles, from orquesta to conjunto. In addition, Donley’s incorporation of the rock and roll rhythm influenced conjunto music as well. There would be no need for a drum set without implementation of the kick drum on the downbeat and the high hat/snare combination on the upbeat. Donley shifted the entire sound of tejano music in Austin as musicians reproduced his new style.

While prior to the 1950s, orquestas may have existed on both sides of the US-Mexico border, Reyna discusses factors such as music education in public schools and lack of financial resources as reasons for the lack of development of the same type of orquesta to develop in Mexico. The equivalent of the modern orquesta tejana does not exist in Mexico, which makes it a musical ensemble distinct to the Tejano community.73 Donley and his contemporaries originated a uniquely Texas-Mexican musical form.

The “Places” of the Austin Tejano Music Scene

The late 1950s offered unique entertainment for Mexican American music fans. The popular bands competed at various venues for the crowd’s affection in battle dances. Donley’s Las Estrellas participated in these contests and were often victorious. A particularly significant battle dance took place at the Skyline Club in 1957. The country venue on North Lamar at Braker Lane (infamous as the site of the last concerts of both Hank Williams, Sr. and Johnny Horton) hosted Mexican dances on Sunday nights. This particular battle dance featured the popular orquesta of Isidro Lopez from the Corpus Christi area alternating songs with “Cowboy” y Las Estrellas.74 Lopez’s ensemble consisted of four saxophones, four trumpets, piano, upright bass, brush drums, and soft electric guitar.75 Las Estrellas was comprised of an alto saxophone, tenor saxophone, trumpet, drums with sticks, electric bass, and Donley on loud electric guitar. In the first round, the groups were evenly matched, playing ranchera-ranchera, polka-polka, bolero-bolero and singing in Spanish. After intermission, Las Estrellas started singing in English with a rock and roll song. Lopez could not compete since he did not have any rock and roll material prepared. Las Estrellas won the battle.76 From this moment on, música tejana would never be the same.

The influence of rock and roll demanded the incorporation of loud drums with sticks and an emphasis on the upbeats, metal mouthpieces for the saxophones, and amplification for the guitar and bass. The performance style of Las Estrellas also had to change from soft and shy to loud and happy. They created “un ruidoso (a huge noise) that attracted the teenyboppers.”77 Compared to the loud electric sound of Las Estrellas, Isidro Lopez with his sophisticated ballads and soft rhythm sections appeared outdated and old-fashioned.

With the establishment of this new tejano music scene, members of orquestas tejanas experienced the transition from a traditional acoustic to a modern electric sound, as did the Mexican-American population of Austin. Del Martinez, the local promoter who gave Donley his moniker, arranged for them to perform regularly at the Skyline Club for its Spanish-language Sunday nights.78 Lalo Campos would make the arrangements for Club Avalon.79 They also made appearances at the City Coliseum and a place near Round Rock called “The Barn.”80 Just as Donley’s music began to raise a “ruidoso,” youth social dance styles based on modern rhythms such as rock and roll, honky-tonk, and rhythm and blues began to usurp traditional, adult ballroom styles. By way of live performances of popular hits in English, these 1950s orquestas amplificadas may be key precursors of the English-dominant recordings by artists of the 1960s Chicano soul genre. Donley and his orquesta are also the beginning of the all-in-one modern dance band in tejano music. Donley’s combination of electric guitar, electric bass, and drums in his ensemble gives him the flexibility to duplicate a varied repertoire in English that follows the multiple popular music charts while continuing to adapt Mexican- and Latin-American popular hits into his tejano aesthetic. Donley’s genius was his ability to relate in performance and on record to a bilingual, multicultural Mexican-American teenager or young adult whose musical tastes were informed by the diverse offerings of urban Texas radio.

Amplification and Música Tejana

According to Donley, “Amplification changed everything.”81 This statement does more than capture a moment in time. The single largest benefit of amplification is the increase in volume produced by the musicians, especially in a dance hall filled with noisy patrons in which the new “sonido moderno” (modern sound) could easily be twice as loud with half the previous number of musicians. Smaller groups had advantages for conducting the band’s business and organizing travel. Additionally, Amaro’s electric bass performance may have made tejano music history. Amaro recalls how “they told me that I was the first electric bass player, Mexicano aqui en (here in) Austin.”82 With Donley and Amaro playing amplified guitars, Las Estrellas became the first modern electric orquesta tejana in Austin and originated the modern electric tejano scene. Amaro also points out, “We were lucky. People liked it the way Manuel changed it. The small group doing big things, you know.”83 David Gutierrez, who performed with Donley from 1964 to 1970, explains that “the rancheras of Jose Alfredo Jimenez with mariachi and the boleros of Trio Los Panchos were converted to orquesta style.” Music was changing from the old style of instrumentals, danzónes, and waltzes to the new style of vocal tunes, polkas, and rancheras.84 Rudy Sanchez, the original saxophonist in Las Estrellas, first noticed Donley’s singing voice when he sang the hits of Fats Domino and Little Richard.85 Carmona recalls that “Manuel was a sensation—The Rolling Stones of Tejano.” Las Estrellas placed the spotlight on the lead singer, and their shows drew young audiences. Many older orquestas could not keep up with Las Estrellas, and some retired. Younger orquestas either adapted to the new standard created by Donley or gave up. Fans and supporters liked the new music and stopped following the old sound.86 While Donley innovated with his incorporation of African-American influences, he also continued to deliver música en español as the majority of his playlist, adapting versions of Los Panchos and Jose Alfredo Jimenez hits into an orquesta amplificada format.

The incorporation of the electric guitar into Mexican-American orquestas represents the next step in a long line of music that has continuously featured string-led melodies and harmonies stretching back to Mexican folk traditions. The amplified “voice” of the electric guitar breathes new life into those traditional acoustic mariachi standards which often showcase violin or harp, and it also finds new modern creative expressions through processes of cross-cultural musical bonding, interethnic musical conversations, and transculturation. Donley heard electric sounds from both Anglo- and African-American communities and plugged those sounds into the canciones rancheras and romanticas that are part of his repertoire as an experienced orquesta tejana guitarist and reinterpreted them in his own modern electric style. As Leon Hernandez commented, the conjuntos tejanos adopted amplification to maintain their viability in a music market with a finite number of bars.87 In this blossoming moment of rock and roll hitting the mainstream, the lines of influence are fluid and dynamic.

Manuel Donley as a Recording Artist

In the two decades following World War II, local companies developed for the primary purpose of recording the musical talent of the Tejano community. Many independent record labels arose throughout the state, the earliest being Ideal Records in Alice (1947), Corona Records in San Antonio (1947), and Falcon Records in McAllen (1948). Armando Marroquín and Paco Betancourt founded Ideal as a joint venture that not only recorded artists but also eventually began pressing their own records. Arnaldo Ramirez launched Falcon after some success in home recording. Manuel Rangel started the Corona imprint in San Antonio to produce local and regional talent. His business flourished through the 1960s and 1970s and was continued by his son, Manuel Rangel, Jr.88 Corona carries the distinction as the first label to record Valerio Longoria, the accordionist credited with incorporating “modern dance band drums in a conjunto.”89 In a later period of record industry expansion, Austin-based Valmon Records, owned by Benjamin Moncivais, recorded Little Joe in 1963 with a cover of the popular Rufus Thomas rhythm and blues song “The Dog.”90

With Austin as a focus for this study and Donley as the trailblazer of the new modern sound in the 1950s, I will be referencing his recordings made with record labels in Austin and San Antonio. My main source of information is the Strachwitz Frontera Collection of Mexican and Mexican American Recordings website, which catalogs information on over 110,000 recordings.91 Relying on the Ideal label from Alice, Texas, to identify sonic characteristics, changes, and developments in música tejana, Peña omits many of the mid-1950s to mid-1960s contributors to orquesta tejana from Austin and San Antonio with recordings on Valmon and Corona.

Donley recorded six 45 rpm records for Corona with his orquesta Las Estrellas, available through the Strachwitz collection database. While these records were made in the early 1960s, they are the most relevant to our timeframe of Donley’s incorporation of the modern sound into tejano music. “Ojitos Verdes” (“Green Eyes”) serves as an example of the modern electric sound; the plucked bass string and kick drum drive the downbeat while the guitar strum and snare/high-hat combination provides the emphasis on the upbeat.92 This rhythm section is a direct incorporation from rock and roll.

While Donley’s recordings with Valmon during the 1960s are outside our 1950s timeframe, it is possible that Donley performed the songs live in the 1950s prior to their documentation on vinyl. While he revolutionized the music with his incorporation of the electric guitar and bass, Donley was still relatively late to the recording studio, even with one in Austin. Raymond Vasquez Jr. and his orquesta were first to record Donley’s arrangement of Roberto Cantoral’s bolero “El Reloj” (“The Clock”). Donley’s origin story of the song’s arrangement reveals how he incorporated the Austin soundscape into his Mexican music construct to create a tejano interpretation:

I got that idea from the University [of Texas at Austin] at one o’clock, they had, the University, they had the chimes, the clock (plucks the guitar strings to the melody of the chime when the clock strikes one from the University of Texas Tower). I was listening to it, I was going by the University, and that gives me an idea, (plucks again) reloj.94

Others to use the clock tower chime reference as part of their introduction include Alfonso Ramos and Sunny Ozuna.95

In 1965, Donley recorded “Flor Del Rio” with Valmon Records, which became his biggest hit, and legend has it encouraged many fathers to name their daughters “Flor.”96 This hit signifies the height of his musical career in his ten-year ascent to the top. Donley’s version is in waltz tempo, and the song, written by Victor Cordero, known for his corridos [epic ballads] like “Gabino Barrera” and “Juan Charrasqueado,” is lyrically a tragic story.97 Donley’s interpretation reinforces the Charro Cantor archetype as a troubadour telling a tale of love and loss.

The music business poses a highly complicated web of relationships between radio, entertainment venues, sound recordings, and, of course, the listening audience. Austin in the 1950s offered a predominantly Spanish-language radio station, KTXN. The Mexican-American community could access radio programming that emphasized the Spanish language and their cultural heritage, which in turn allowed for the development of a youth population that was growing up with radio broadcasts in Spanish and English. These same youngsters, Donley among them, also attended public dances, and as the new sound of rock and roll gained popularity, so did the demand to hear those songs performed live. As the rock and roll elements of amplified guitars and loud drums fused with tejano music, the tacuachito dance form developed as the new standard for dancing to the polka beat. The dissemination of all these advancements occurred as Donley and his contemporaries toured the state with their live performances. Yet for Donley, the lack of sound recordings produced by Las Estrellas in the early years may well have deprived him of proper credit for his musical innovations.

Donley’s Modern Sound

In 1955, Manuel “Cowboy” Donley reduced the large orquesta tejana to six members to get at the heart of what became the new sound of música tejana: the use of electric guitar paired with electric bass and loud drums. The smaller ensemble produced a new sound with lyrical, rhythmic, and sonic changes. This shift away from soft ballroom instrumentals to loud popular music marked a milestone in the development and progression of música tejana. Donley explains that the “electric guitar was playing lead, you know, and then singing and the big bands went out of business.”98 In addition, Donley’s new amplified and streamlined ensemble cut the trumpet section in half, sometimes by two-thirds, and the saxophone section by at least a third. Amplification allows for a reduction in the numbers of members while still producing a big sound. Prior to amplification, to be louder actually required more instruments.

All of the factors in transition, from ballroom stock arrangements to popular music versions, from instrumental pieces to narrative song, from prolonged notes to single staccato notes, from formal dance styles to vernacular dance styles, coalesce to create the modern tejano scene in the 1950s. The electric influences of rock and roll, country, rhythm and blues, and multiple Mexican genres make the amplification of the 1950s the universal sound in tejano music. The previous separation of working-class and middle-class as distinctive audiences became blurred by the newly established youth music market. The fresh electric sounds came to dominate both orquesta and conjunto styles where hit songs were now determined by adolescents and not their adult parents.

This period in música tejana history between Beto Villa and Little Joe y La Familia requires more attention. As Little Joe himself has noted, “I feel [Donley] has not gotten all due him.”99 This approximate ten-year span from 1955 to 1965 witnessed a surge in record labels and music production powered by advances in sound technology and sound recording equipment. Musical creativity also flourished among musicians due in part to their mutual admiration and their willingness to explore multiple popular genres simultaneously. The youth subculture took over the primary music market, and their impact resonated in other ancillary music markets.

In the 1950s, tejano artists initiated technical and stylistic innovations that advanced the sound and rhythm of the entire genre and in turn affected the participatory dance movements of the audience. Donley explains the switch to a modern sound: “Well, nobody else was playing electric guitar, they were all playing acoustic, you know, and I came out with the electric guitar and that put a whole new sound into orchestra and I got electric bass, electric guitar, and a loud drum.”100 Donley and his contemporaries incorporated an amplified sound into their ensembles with the use of electric guitar and bass similar to developments in Anglo- and African-American popular music and introduced new musical configurations in their ensembles, a sonic distinction that split the tejano music historical timeline into traditional acoustic and modern electric. This new music prepared the way for the tejano music explosion of the 1990s with artists such as Emilio, Selena, La Mafia, and Grupo Mazz.

1. I use the terms tejano music, música tejana, and Texas-Mexican music interchangeably as the Spanish-language music created and produced by Texas-Mexican communities in Texas, the United States, and around the world.

2. Brad Tolinski and Alan Di Perna, Play It Loud: An Epic History of the Style, Sound, and Revolution of the Electric Guitar, (New York: Doubleday, 2016), 16-17, 89-91.

3. Manuel Donley, interview by the author, December 1, 2018.

4. The twelve-string classical guitar virtuosity and extensive sound recording career of Lydia Mendoza is well documented. See Dale Miller, “Lydia Mendoza: The Lark of the Border,” Guitar Player, August 1988; Michael John Simmons, “12-String Power: The Master Players and Makers of the Double-Course Guitar,” Acoustic Guitar, November 1997; Lydia Mendoza, Chris Strachwitz, and James Nicolopulos, Lydia Mendoza: A Family Autobiography (Houston: Arte Público Press, 1993).

5. “Tejano Music Legend Manuel ‘Cowboy’ Donley, 87, Still Strumming,” NBC News, October 1, 2014.

6. Sarah Wimer, “The Godfather of Tejano Music: The Long Musical Journey of Manuel ‘Cowboy’ Donley,” accessed February 15, 2015.

7. Américo Paredes describes a second Mexico as “Mexico de Afuera” (Mexico abroad) composed of all the persons of Mexican origin in the United States. Américo Paredes, “The Folklore Groups of Mexican Origin in the United States,” in Folklore and Culture on the Texas-Mexican Border, ed. Richard Bauman (Austin: Center for Mexican American Studies, University of Texas at Austin, 1993), 3.

8. Manuel H. Peña, The Mexican American Orquesta: Music, Culture, and the Dialectic of Conflict (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1999), 108.

9. Yolanda Broyles-González and Lydia Mendoza, Lydia Mendoza’s Life in Music / La Historia De Lydia Mendoza: Norteño Tejano Legacies (New York: Oxford University Press, 2001), 193.

10. José B. Cuellar, “El Saxofon in Tejano and Norteño Music,” in Collected Work: Puro Conjunto: An Album in Words and Pictures—Writings, Posters, and Autographs from the Tejano Conjunto Festival En San Antonio (1982–1998), eds. Juan Tejeda and Avelardo Valdez (Austin: Center for Mexican American Studies, University of Texas at Austin, 2001), 136.

11. Peña, The Mexican American Orquesta, 150, 140, 158. Oscar Martinez, Tejano Music Talk, OSMART, July 2009, 28-29.

12. Manuel H. Peña, The Texas-Mexican Conjunto: History of a Working-Class Music (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1985), 9-14.

13. Yolanda Broyles-González, “Ranchera Music(s) and the Legendary Lydia Mendoza: Performing Social Location and Relations,” Chicana Traditions: Continuity and Change, eds. Norma E. Cantú and Olga Nájera-Ramirez (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2002), 188.

14. Vicente Mendoza in his classification of lyrical Mexican songs categorizes mañanitas, serenatas and despedidas as fulfilling a specific purpose or in relation to the particular time of day in which they are sung (“Segun el uso a que se destine or la hora en que se cante”). Vicente T. Mendoza, La Canción Mexicana: Ensayo de Clasificación y Antología (México, D.F.: Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1998), 69.

15. María-Cristina García, “Charreria,” Handbook of Texas Online, Texas State Historical Association, last modified June 12, 2010.

16. Rogelio Agrasanchez and Charles Ramírez Berg, Cine Mexicano: Posters from the Golden Age, 1936-1956 / Carteles de La Época de Oro, 1936-1956 (San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 2001), 73, 77.

17. Alan Axelrod and Dan Fox, Songs of the Wild West (NewYork: Metropolitan Museum of Art / Simon & Schuster Books for Young Readers, 1991), 47-51.

18. Jim Bob Tinsley, For a Cowboy Has to Sing: A Collection of Sixty Romantic Cowboy and Western Songs, Covering the Fifty-Year Golden Era of Popular Standards between 1905 and 1957 (Orlando: University of Central Florida Press, 1991), 130-134.

19. “Gene Autry – Actor,” IMDb, accessed February 21, 2019.

20. “Gene Autry – Soundtrack,” IMDb, accessed February 21, 2019.

21. “Roy Rogers – Soundtrack,” IMDb, accessed February 21, 2019.

22. Donley, interview by the author, February 17, 2019.

23. Charles R. Townsend, San Antonio Rose: The Life and Music of Bob Wills (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1986), 193.

24. Donley, interview by the author, October 27, 2018.

25. Belinda Acosta, “Beautiful Songs and Good, Heavy Sounds,” Austin Chronicle, November 11, 1998.

26. “Display Ad 75,” Austin Statesman, May 15, 1959, 22.

27. Acosta, “Beautiful Songs.”

28. Wimer, “The Godfather.”

29. Acosta, “Beautiful Songs.”

30. J. Richard Haefer, “Requinto,” Grove Music Online, last modified 2016. Daniel Party, “Los Panchos,” Grove Music Online, last modified 2014.

31. Acosta, “Beautiful Songs.”

32. Donley, interview by author, December 3-4, 2011.

33. Party, “Los Panchos.”

34. Yolanda Moreno Rivas, Historia de La Música Popular Mexicana (México, D.F.: Consejo Nacional para la Cultura y las Artes, 1995), 132. Translation by the author.

35. Juan Castillo, “At 83, Tejano Music Pioneer Still Playing,” Austin American-Statesman, September 12, 2012.

36. Mendoza, La Canción Mexicana, 41. Translation by the author.

37. Castillo, “Tejano Music Pioneer.”

38. Donley, December 3-4, 2011.

39. Donley, December 1, 2018.

40. Donley, December 3-4, 2011.

41. Wimer, “The Godfather.”

42. Steve Waksman, Instruments of Desire: The Electric Guitar and the Shaping of Musical Experience (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1999), 48.

43. Donley, December 3-4, 2011.

44. Ibid.

45. Mitchell K. Hall, The Emergence of Rock and Roll: Music and the Rise of American Youth Culture (New York: Routledge, 2014), 11-12.

46. Manuel Donley Papers and Record Collection.

47. Hall, 12-16.

48. Ibid., 24.

49. Donley, December 3-4, 2011.

50. Hall, 15-16.

51. “Display Ad 75 -- no Title.” The Austin Statesman (1921-1973), May 15, 1959. 22.

52. Manuel Donley Papers and Record Collection.

53. Ibid.

54. Raymond Williams, Marxism and Literature, (New York: Oxford University Press, 1977), 121-127.

55. Peña, The Mexican American Orquesta, 243.

56. Guadalupe San Miguel, Tejano Proud: Tex-Mex Music in the Twentieth Century, (College Station: Texas A&M University Press), 2002, 69-74, 86-87.

57. Donley, December 3-4, 2011. Andres Zuniga, interview by the author, December 2, 2014.

58. Texas Music Museum, “Austin Tejano Collection.”

59. Donley’s formation of Las Estrellas predates the establishment of Oscar Martinez’s orquesta by three years. The Oscar Martinez band was organized in 1958.

60. Acosta, “Beautiful Songs.”

61. Castillo, “Tejano Music Pioneer.”

62. Guadalupe San Miguel, Jr., “Música Tejana: Nuestra Música,” Journal of Texas Music History 1, no. 1 (Spring 2001): 9.

63. Donley, December 3-4, 2011.

64. Mike Amaro, interview by the author, November 18, 2018.

65. Ibid.

66. Castillo, “Tejano Music Pioneer.”

67. Donley, December 3-4, 2011.

68. Castillo, “Tejano Music Pioneer.”

69. Donley, December 3-4, 2011.

70. Mike Carmona, interview by the author, December 22, 2014.

71. Ibid.

72. Leon Hernandez, interview by the author, October 27, 2018.

73. José Reyna, “Tejano Music as an Expression of Cultural Nationalism,” in Collected Work: Puro Conjunto: An Album in Words and Pictures—Writings, Posters, and Autographs from the Tejano Conjunto Festival En San Antonio (1982–1998), eds. Juan Tejeda and Avelardo Valdez (Austin: Center for Mexican American Studies, University of Texas at Austin, 2001), 195.

74. Wimer, “The Godfather.”

75. This battle dance may have taken place prior to Lopez adding the accordion and bajo sexto to his orquesta ensemble.

76. Donley, December 3-4, 2011.

77. Ibid.

78. Amaro, Donley, December 4, 2011; Donley Papers and Record Collection, calendars for 1963 and 1964 with performance dates.

79. Ibid.

80. Ibid.

81. Donley, December 3-4, 2011.

82. Amaro, November 18, 2018.

83. Ibid.

84. David Gutierrez, interview by the author, December 17, 2014.

85. Rudy Sanchez, interview by the author, December 4, 2014.

86. Carmona, December 22, 2014.

87. Hernandez, October 27, 2018.

88. Alex LaRotta, “Música Tejana Recording Pioneers,” in Cowboys, Cops, Killers, and Ghosts: Legends and Lore in Texas, ed. Kenneth L. Untiedt (Denton: University of North Texas Press, 2013), 117-121.

89. Peña, Texas-Mexican Conjunto, 82-84.

90. LaRotta, “Música Tejana Recording Pioneers,” 123.

91. The Strachwitz Frontera Collection of Mexican and Mexican American Recordings, University of California Regents & The Arhoolie Foundation, 2015, accessed February 2, 2019.

92. “Ojitos Verdes,” by Manuel Donley y su Orquesta Las Estrellas, The Strachwitz Frontera Collection.

93. “El Reloj” by Raymond Vasquez Jr., Valmon Records, catalog number VN-1-023-A. Donley’s version also appears on Valmon VN-1-167-A, Strachwitz Frontera Collection.

94. Donley, December 1, 2018.

95. “El Reloj” by Alfonso Ramos, El Zarape Records, catalog number ZLP-1005, Strachwitz Frontera Collection. “El Reloj” by Sunny & The Sunliners, Tear Drop Records, catalog number TDLP-2006, Strachwitz Frontera Collection.

96. Castillo, “Tejano Music Pioneer.”

97. “Flor Del Rio,” by Manuel Donley y Las Estrellas, Valmon Records, catalog number VN-1003, Strachwitz Frontera Collection.

98. Donley, December 1, 2018.

99. “Tejano Music Legend Manuel ‘Cowboy’ Donley,” NBC News.

100. Donley, December 1, 2018.