JTMH Volume 20 | Outlaws & Armadillos

Outlaws & Armadillos: Country’s Roaring ‘70s at the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum

Jennifer Ruch

The Country Music Hall of Fame is situated in the heart of downtown Nashville. The 350,000 square foot architectural goliath nestles between bustling 4th and 5th Avenues and is a cornerstone of Nashville’s music heritage tourism. The museum is also within walking distance of other popular music attractions such as the Musicians Hall of Fame, Hatch Show Print, the Nashville Music Garden, the Music City Walk of Fame, and the historic Ryman Auditorium, former home of the Grand Ole Opry. While the Hall of Fame was established in 1961 and the original building opened in 1967, the current structural iteration of the museum is just short of twenty years old with a sizeable renovation and expansion in 2014. The museum maintains a wealth of permanent and temporary exhibits and is one of the premier institutions in innovative exhibition design and emerging professional trends in regional microhistory storytelling.1

The scope of the museum moves beyond the sole commemoration of Hall of Fame inductees by the Country Music Association to include a wide range of public education programs and a growing permanent collection aimed at collecting, preserving, and interpreting the evolving history and traditions of country music.2 Songwriters’ nights, roundtable artist talks, teacher resource programs, and youth instrument lessons are but a few of the museum’s current public programming offerings. The permanent collection includes digital archives, recorded sound collections accompanied by a growing oral history project, and a wealth of material objects. Many of the current exhibits, such as We Could: The Songwriting Artistry of Boudleaux and Felice Bryant, Brooks & Dunn: Kings of Neon, Kacey Musgraves: All the Colors, Still Rings True: The Enduring Voice of Keith Whitley are artist-centered narratives that offer the visitor a glimpse of personal artistry and performative style across a broad spectrum of country music’s diverse terrain.

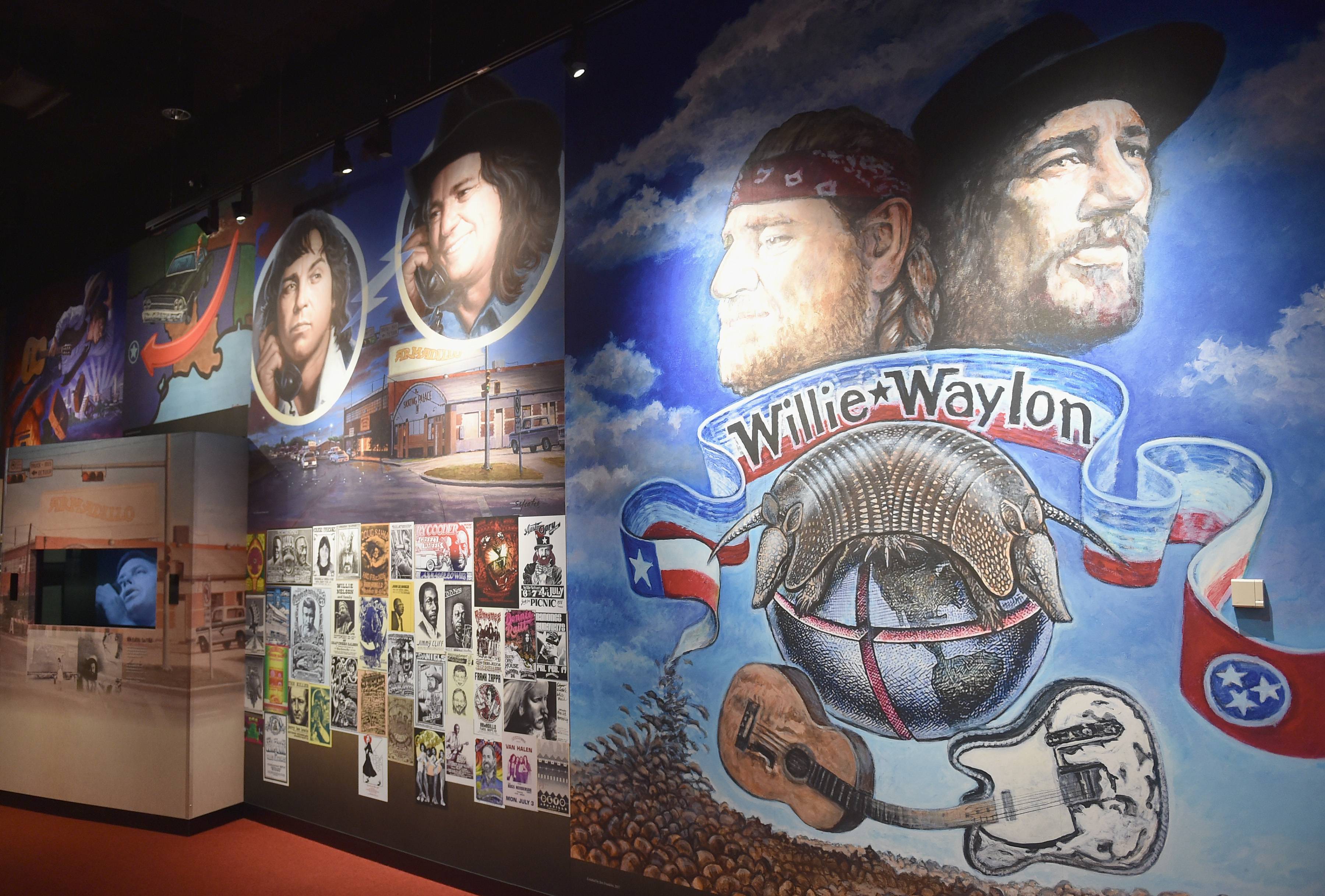

On May 25, 2018, the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum premiered Outlaws & Armadillos: Country Music’s Roaring ‘70s as a temporary three-year exhibit housed in one of the facility’s main halls. The exhibit, which runs until early 2021, explores the musical and cultural exchange between Austin and Nashville throughout the 1970s progressive country movement. Willie Nelson, Jerry Jeff Walker, Kris Kristofferson, Waylon Jennings, Townes Van Zandt, Doug Sahm, and Hondo Crouch are just a few of the characters the exhibit highlights. The two cities, both historically rich with musical legacy, share a complicated relationship. Outlaws & Armadillos shines a light on the intricacies of regional country styles and the process of music-making in two contrasting localities. The creative process for country music in Nashville historically follows a more regimented writing, recording, and production process. This naturally aligns with the city’s history as a music industry town. The countercultural appeal of late 1960s and early 1970s Central Texas facilitated a more experimental environment in the way of musical expression and performance. The museum details the “smooth Nashville Sound” of the mid-twentieth century as “commercially successful,” but “creatively stifling."3 At the same time, Austin experienced a subcultural transformation that welcomed mainstream outsiders and eclectic musical perspectives. This exhibit uses that relationship to illustrate the tangible symbolism of outlaw country music that ultimately works to dissect both cities’ intangible regional legacies.

Beyond its distinctive Texas focus and countercultural flair, Outlaws & Armadillos marks an important moment for regional music narratives in large cultural institutions. This incorporation denotes a shift in the way music museums interpret regional histories and, more importantly, the ways in which public historians are using the material of popular music to answer important questions regarding regional crossroads. The museum’s critical interpretation of popular music has grown in recent years, and the Country Music Hall of Fame’s approach to topical musical narratives continues as a pioneering marker for the craft of exhibition development and interpretation. The Hall of Fame is no stranger to complicated musical narratives. One example is their 2004 exhibit, Night Train to Nashville: Music City Rhythm & Blues, which explored black music in Nashville and its integral connections to the traditions of country music. The museum has a distinguished history of pushing interpretive boundaries, and Outlaws & Armadillos is its most recent example.

At the entrance of the Outlaw & Armadillos exhibit space, a large panel overlaid with an archival image of Willie Nelson’s 1978 Fourth of July Picnic greets visitors. At the opposite side of the entrance is a sepia-toned headshot of a young, short-haired, clean-shaven Willie Nelson from his time as a Nashville songwriter. Juxtaposing these two initial images sets a thematic tone for the rest of the exhibit, a tone that subtly weaves together the narrative tension between the Austin scene and the Nashville industry. The layout of the space is relatively free-flowing. Visitors can move around the exhibit hall without having to adhere to any particular sense of direction. Text panels, photographs, visual art, and artifact cases fill the outer walls, while large temporary panels and pillars fill the middle of the room. The exhibit’s chronology runs from the late 1960s to the late 1970s. A mix of original audio and archival video recordings from concerts and interviews plays on a loop throughout the space. It is worth noting that the Hall of Fame also commissioned new footage, interviews, and in-exhibition art by many of Austin’s key players in the progressive country scene including visual artists such as Kerry Awn, Jim Franklin, and Bob “Daddy-O” Wade. The exhibit accommodates small children with in-exhibit activities that range from an armadillo coloring page, an artifact scavenger hunt, and a visually interactive game projected from the ceiling onto the floor where visitors can stomp animated armadillos as they wander onto a cartoon highway.

The exhibit’s narrative begins with sections devoted to the local musical terrains of both Nashville and Austin at the end of the 1960s. For Austin, this means a heavy emphasis on performance, while the Nashville narrative demonstrated the city’s role as a hub for mainstream country music recording and production. Wall space in this area is decorated with a colorful collage of psychedelic concert posters designed by Jim Franklin, Tony Bell, and many others that illustrate the swelling underground of Austin in the late 60s and the artists that brought it to life. Janis Joplin, Freddie King, and Mance Lipscomb are a few artists highlighted. The narrative unfolds to pay special attention to the Armadillo World Headquarters as the cultural hotbed of the progressive country scene both performatively and as a gathering space for the subculture, but also thoroughly acknowledges other important venues such as the Broken Spoke, Antone’s, Luckenbach, the Cheatham Street Warehouse, and the Soap Creek Saloon. Outlaws & Armadillos ends with a short commentary on the end of the outlaw scene. One panel describes its demise as “a scene that had gone from vibrant to tired,” with many artists abandoning the uniquely Texan identity for pop-driven success, while others distanced themselves from the scene for personal or health reasons.4 The narrative is strong. However, navigating the space while maintaining a coherent grasp on outlaw country’s chronological story does prove to be a minor challenge. Similarly, a visitor with no knowledge of this history might have some difficulty fully engaging with its timeline.

On the whole, the overwhelming strength of Outlaws & Armadillos is the use of a distinctly regional material collection. The Hall of Fame team researched in and borrowed from the extensive collections of both the Austin Museum of Popular Culture and the Wittliff Collections at Texas State University. Aside from the concert posters and visual art, the exhibit uses material culture of the everyday to demonstrate how deeply the outlaw scene had saturated the Texas vernacular. While one artifact case showcases the mythology of the armadillo as a form of Texas counterculture and enduring cultural heritage, another case filled with ephemera demonstrates the ways in which progressive country transformed Texas beer culture through the efforts of Lone Star’s Jerry Retzloff. Ticket stubs, concert t-shirts, handbills, tour jackets, bandanas, guitar picks, and beer glasses throughout the exhibit speak to a shared collective experience among scene participants and effectively act as relatable markers of material possession. These are items that large cross-sections of likely visitors both own and cherish. The use of common ephemera in this exhibit space facilitates an elevated sense of engagement that moves beyond totems of celebrities past and, instead, encourages genuine emotional response.

A common problem among museums that take on popular music narratives is the risk of exhibiting objects that speak only to star power or authoritative possession and relates directly to broader issues of representation in music narratives. How do visitors see themselves reflected in these stories? While there are many compelling objects in the exhibit that are strategically utilized to provoke star-studded reactions, such as Willie Nelson’s Converse shoes, Guy Clark’s Randall knife, and Kris Kristofferson’s Army jacket, Outlaws & Armadillos successfully finds balance between exclusive content and the material languages that appeal to a large cross section of visitors. Overall, this exhibit points to an important interpretive moment for popular music in the museum, one that is inclusive of historically complicated intersections of regionality, industry, and the subcultures they foster.

Notes

1. For more on the Hall of Fame's origins and context, see Diane Pecknold, The Selling Sound: The Rise of the country Music Industry (Durham: Duke University Press, 2007), 189-199.

2. Country Music Hall of Fame Mission. https://countrymusichalloffame.org/

3. Country Music Hall of Fame Exhibit Information. https://countrymusichalloffame.org/exhibit/outlaws-armadillos-countrys-roaring-70s/

4. “Outlaw Farewell” panel in Outlaws & Armadillos" Country's Roaring '70s.Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum.