JTMH Volume 21 | Houston Roots

Houston Roots and the Texas Gulf Coast Sound Embodied in the Music of Los Skarnales and Nick Gaitan & the Umbrella Man

Mary Manning

Houston is an industrial city, the home of the Ship Channel, and the region’s petrochemical industry hub since the early 20th century. Houston has historically attracted those looking for work who brought with them music reflecting their cultural heritage. Continual migration as the twentieth century progressed ensured that Houston’s music continued to reflect its rich multicultural diversity. Houston’s music is influenced by and influences the region’s music—the Texas Gulf Coast sound. Houston area recording studios and record producers were crucial elements of developing this regional sound.1

Historically, Houston’s roots music was highly hybridized, a coalescence of older genres combined with developing and often popular musical sounds. While genre combining to create a local sound is not specific to the Texas Gulf Coast region, Houston’s roots music is as idiosyncratic as the Bayou City itself. This unique combination of hybridized roots genres has influenced two bands—Los Skarnales and Nick Gaitan & the Umbrella Man—that have merged these roots genres with popular music to create their version of the Texas Gulf Coast sound. The author conducted comprehensive interviews with musicians from these two bands, namely Felipe Galvan, Nick Gaitan, and Roberto Rodriguez III. These musicians serve as key oral historical sources to better understand the recent evolution of roots music in Houston.2

Roots Music in Houston and the Region3

Houston has historically attracted immigrants seeking work from the east (Louisiana) and the south (Mexico and border communities) and is a cultural and musical amalgamation of all points in between.4 During the twentieth century, Houston musicians were influenced by this region’s roots genres, including those originating east of Houston (e.g., zydeco, Cajun, and swamp pop) and those from south of Houston (e.g., traditional música tejana, orquesta, conjunto, and Tejano).5 Musicians blended these sounds with country, jazz, R&B, and rock and roll to create further hybridized music. As journalist Steve McVicker explains, Gulf Coast music crosses borders “between Texas and Louisiana, and Texas and Mexico, between black and white, and brown.”6 The music of this region creates a Texas Gulf Coast sound, which is both a historical and living music—earlier regional music reimagined by contemporary popular music.

Texas and Houston have long been known for their blues. Huddie Ledbetter, also known as “Lead Belly,” was born in Caddo Parish on the northwest corner of Louisiana near the Texas border and grew up on a tenant farm in East Texas. Ledbetter spent much of his life between Louisiana and Texas, and “in the late 1920s, Lead Belly supported himself by working as a driver and maintenance worker in Houston and around Shreveport.”7 Ledbetter’s song “Midnight Special” contains the advice, “If you ever go to Houston/Boys, you better walk right.”

In the late 1920s, Gilbert Jacquet, a Louisianan Creole transplanted to Houston, performed with Milt Larkin, and together they created a bluesy jazz sound that blended the rural with the urban. In the 1930s, this “blues saturated” Houston jazz sound evolved to big band swing, producing some of the most highly influential Texas tenor saxophonists.8 Arnett Cobb, Illinois Jacquet (son of Gilbert), and Eddie “Cleanhead” Vinson performed with Milt Larkin. The latter encouraged the developing Texas tenor sound as a way for the saxophones to be heard above the rest of the band.9 Cobb, Jacquet, and Vinson later performed with top national acts.10 The Texas Tenor sound influenced swing, bebop, blues, and R&B, and became a staple of the 1940s and ’50s R&B sound.11

One of the most influential singers and guitarists in postwar blues history was Houstonian Sam “Lightnin’” Hopkins, who recorded over one hundred songs at Houston’s Gold Star recording studio.12 Clarence “Gatemouth” Brown, Bobby “Blue” Bland, and other acts would be associated with Don Robey’s Duke and Peacock Records in Houston’s Fifth Ward. Gatemouth had roots in East Texas and Louisiana and incorporated blues, country, jazz, Cajun music, and R&B into his repertoire.13

Long-time Houstonian Cliff Bruner was a world-class fiddle player who melded rural and city sounds and performed with Fort Worth’s Milton Brown and His Musical Brownies as Western swing developed. In 1936 he returned to Houston after Brown’s sudden death to form the Texas Wanderers. Making the transition from large-band Western swing to the “small group electric honky tonk of the forties,” the Texas Wanderers included many legendary performers.14 Houstonian Johnny Bush, who composed and recorded “Whiskey River” in 1972, grew up listening to area musicians such as Floyd Tillman, Ted Daffan, and Pappy Selph’s Blue Ridge Boys. As Bush explains, “Honky tonk fiddle, as we played it in Texas, was a combination of western-swing and Cajun.”15 George Jones recorded “Why Baby Why” in 1955 at Houston’s Goldstar early in his career, and Willie Nelson recorded “Night Life” there in 1960.16

From Louisiana, Black Creole and white Cajun music traveled to find a home in Houston, especially after the Mississippi River flood in 1927.17 Creoles brought their la-la music (rural and acoustic) to Houston’s Black urban areas, incorporating blues and R&B with electric instrumentation. The sound hybridized as they moved back and forth between Louisiana and Houston, ultimately birthing zydeco.18 Early in his career, Clifton Chenier, a long-time Houston resident with roots in Louisiana and the “king of zydeco,” performed and recorded in Houston.19

After WWII, Cajun and Creole musicians flocked to the Golden Triangle area of Beaumont, Port Arthur, and Orange, Texas, to find work in the oil and defense industries but maintained close ties to Acadiana.20 These musicians often performed and recorded in Houston. For example, Harry Choates’s 1946 #4 Billboard hit “Jole Blon” (more commonly spelled “Jolie Blonde” in subsequent recordings) earned its long-standing reputation as the Cajun national anthem and was recorded at Gold Star.21 Such recordings were essential to the development of Cajun and Creole music and other genres, including country and western, rhythm and blues, rock and roll, and rockabilly. From Beaumont, Moon Mullican, the “King of the Hillbilly Piano Players,” performed with Houstonian Bruner in the Texas Wanderers and Tillman and Daffan in the Blue Ridge Playboys. Mullican’s boogie style greatly influenced rockabilly.22

Louisiana during his early career and adopted key musical elements of the region. Photo by: Gene Pugh (CC-BY-SA).

During the late 1950s, Harold W. “Pappy” Daily recorded several hits at Gold Star that featured musicians from the Golden Triangle area and bridged country, rockabilly, rock and roll, and swamp pop. Beaumont’s J.P. “Big Bopper” Richardson started his career performing country music, but his 1957 hit “Chantilly Lace” was an early rock and roll sensation. Port Arthur’s Johnny Preston (né John Preston Courville) scored a hit with “Running Bear” in 1960.23 Both songs landed on the pop and R&B charts.24

Swamp pop is a sub-genre of rock and roll that developed in the mid-1950s and blends Cajun and Creole music with New Orleans-style R&B with country and western.25 Cajun swamp pop performers from the Golden Triangle region included Preston and “Jivin’ Gene” Bourgeois, who had a hit with “Breaking Up is Hard to Do” in 1965.26 In 1959, Creole musicians Cookie & his Cupcakes from South Louisiana were responsible for “Matilda,”the quintessential swamp pop recording.27 While white Cajuns and Black Creoles performed the genre, Freddy Fender adopted key musical elements of the region, particularly swamp pop; he helped bridge the sounds of South Texas and Louisiana.28

In the 1910s, Tejanos (Texans of Mexican descent) and emigrant Mexicans escaping the Mexican Revolution began arriving in Houston.29 Lydia Mendoza, also known as La Alondra de la Frontera, was born in Houston in 1916. In her youth, she performed rancheras and other traditional música tejana with her family at barbershops, restaurants, and other Second Ward settings, including Our Lady of Guadalupe church.30

Like Western swing, orquesta developed from the big band swing jazz of the 1930s, which was enormously popular across a broad spectrum of listeners, including upwardly mobile, middle-class Tejanos. This big band music, often performed in Spanish, incorporated South Texas’s and Mexico’s sounds and marked a shift from rural to urban, from ranchera to orquesta.31 Reflecting this development, Houston ranchera band Alonzo y Sus Rancheras transitioned to performing orquesta and became Alonzo y Su Orquesta, trading in their traditional borderland instruments, such as accordion and bajo sexto, for horns.32 In contrast, conjunto developed about the same time but primarily appealed to a rural, working-class audience. Accordion-based conjunto developed in South Texas closely aligns with traditional Mexican music—particularly the norteño music in the northern part of Mexico.33 Houston conjunto remained regionally based primarily until the 1980s when the band La Mafia established national popularity.34

Chicano soul developed in the 1960s, a decade when soul music reflected the political climate.35 Chicano soul in Houston drew from regional sounds. As Tyina Steptoe explains, “The heavy infusion of Texas blues . . . distinguished their sound from the rhythm and blues produced by Mexican Americans in places like Los Angeles.”36 Chicano soul was aired on Houston’s Black radio stations and featured by popular DJ Skipper Lee Frazier. When Chicano soul performers played in Black nightclubs, the audiences were often surprised to discover the singers were Chicano performers.37 However, when Chicano soul bands performed for a Mexican-American audience, they would perform a wider variety of music, including música tejana. Sunny Ozuna recorded his 1962 hit “Talk to Me” with the Sunliners, a band that featured Houston musicians. Other La Onda or Chicana or Chicano soul bands from Houston include the Starlights, Rocky Gil and the Bishops, and the Comets.

Tex-Mex rock and roll origins are primarily associated with San Antonio musicians Doug Sahm, Augie Meyers, and the Sir Douglas Quintet, which was popular in the 1960s and 1970s.38 In 1989, Sahm and Meyers’s musical efforts evolved into the Texas Tornados, with Freddy Fender, Flaco Jimenez, and others. Jimenez brought the accordion and conjunto style, while Fender brought country and Cajun sounds to the group.

The influence of música tejana extends beyond the Texas border. From Los Angeles, Los Lobos were influenced by Tex-Mex rock and roll and the Mexican folk music at the root of música tejana. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, members from Los Lobos, along with Flaco Jimenez, Augie Meyers, and Freddy Fender from the Texas Tornados, performed with Los Super Seven, a collective that blended Tejano, Latin American, and Cuban music with blues, R&B, country, jazz, and rock and roll.39

Ska-Punk, Tex-Mex, Roots Music, and the Texas Gulf Coast Sound: Los Skarnales and Nick Gaitan & the Umbrella Man

At the turn of the 21st century, two bands that epitomize the fusion of influences that define the Texas Gulf Coast sound emerged from Houston: Los Skarnales (formed in 1994) and Nick Gaitan & the Umbrella Man (formed in 2006). The rest of this article will focus on these bands—how they are influenced by and reflect Houston and regional roots sounds, and how they combine these sounds with popular music to create their version of the Texas Gulf Coast sound.

Los Skarnales—a Spanish-Language Ska-Punk Band

The Spanish-language ska-punk band Los Skarnales was formed in 1994 by Felipe Galvan and Desorden bandmate Jose Rodriguez. The band’s name playfully combines “ska” with “los carnales” (the brothers, but not blood brothers, or more loosely, the homeboys). Skarnales formed at the height of the third wave of ska in the 1990s.40 Mixing and melding was a hallmark of ska’s third wave, and the sound varied greatly from one band to the next—from traditional ska to pop to punk. The third wave is primarily associated with the US but also has enjoyed popularity in Mexico.41 The inclusion of Spanish language added another twist to their third-wave ska-punk, and Skarnales, perhaps the first Spanish-language ska-punk band in Texas, is undoubtedly its most enduring.

British and American punk (particularly the Clash and the Ramones) heavily influenced Galvan and Rodriguez. Galvan was also influenced by Spanish-language punk bands in Mexico, such as Maldita Vecindad and Massacre 68, and others in Spain, including La Polla Records, Eskorbuto, and Decibelios. Galvan appreciates how each of these bands “represents where they’re from” and likewise creates music to “represent [his] Mexican-American culture.”42 During the band’s formation, Galvan introduced to bandmate J. Rodriguez the French band Mano Negra, who mixed mambo and rockabilly, and suggested, “Let’s try and do something like that, you know, but a Chicano version.”43

Galvan, Pachuco Style, and Creating the “Chicano Version”

Galvan is a first-generation Texas Mexican, born in Pharr, a border town across from Reynosa, Mexico, where his parents and older siblings were born. The music of the South Texas border influenced Galvan and his parents, who were musicians.44 However, pachuco, which originated in El Paso in the late 1930s, also influenced Galvan. Pachuco’s audience was primarily Mexican American, and its popularity spread to other major cities, including Houston.45 Tara Lopez explains that pachuco was “a force of cultural and political resistance against such overt forms of white supremacy in the early to mid-20th century.”46 As pachuco was a movement of protest in the 1930s and 1940s, so too was punk in the latter part of the twentieth century.

Pachuco was a culture and a way of dressing and speaking. Pachucos wore zoot suits, listened to swing jazz, and spoke in a slang called caló, and the Pachuco boogie that followed WWI was heavily influenced by jump blues and Cab Calloway, whom Galvan greatly admires. The caló slang from pachuco would later become associated with the Chicano movement and remains in use today.

Galvan is also influenced by Tin Tan, a character created by Germán Valdés and fashioned after Cab Calloway.47 Galvan describes growing up with the character Tin Tan in the home and how the character influenced him:

And me growing up, I had always liked that style, you know, because in Mexican families, the moms and the families are always watching Pedro Infante movies and Tin Tan movies from that era. And Tin Tan . . . here goes this comic that brought the pachuco image to the movies and he was like a real good singer, he was like a real good comic, he was a real good dancer, he was good looking, he was like a ladies’ man…So, it was like one person, he had all these qualities, you know, and me growing up as a kid, I was like, “Man, that’s badass, this guy is amazing, you know?”48

Los Skarnales incorporates the pachuco style and the image of Tin Tan into their aesthetic. As early as their Desorden days, Galvan and bandmate J. Rodriguez employed pachuco style to create their own style. Galvan explains:

I mean, we started dressing like pachucos, too, you know? To me, that was more punk rock, too, instead of having a green mohawk that pretty much didn’t stand for anything from my roots, you know? That’s more like UK punk rock or . . . you know, I’m not from England, so . . . Or somebody that grew up in New York with CBGBs or something like that. So, we started getting into like the ’50s vintage stuff, real close to the pachucos, you know?49

Galvan dresses in pachuco style and employs in his lyrics and speech caló terms such as orale (meaning something similar to “right on,” “all right,” or “that’s right”). Galvan notes, “Our style, with the pachuco and the live shows and everybody’s personalities, it’s already set, like, Skarnales style.”50

The Pachuco Boogie Sound System Era of Los Skarnales

Skarnales’ lineup has frequently changed throughout the twenty-five-plus years of the band. One of these lineups has come to be known as the Pachuco Boogie Sound System; however, it was not identified as such until after the release of the album of the same name in 2005. Not until Tejano accordionist Roberto Rodriguez III joined in 2002 was the lineup complete. The lineup’s name evokes the pachuco boogie’s jump blues and the sound systems developed by DJs in Jamaica. During the Pachuco Boogie Sound System era, the band incorporated reggae and other Jamaican roots music such as mento with pachuco boogie’s jump blues. It featured pared-down instrumentation without horns and a more acoustic approach.

Los Skarnales emphasized their roots sound during this era of the band. While still incorporating ska elements, particularly with the keyboards, Pachuco Boogie’s jump blues sound was strengthened through Gaitan’s upright bass. As the lineup initially formed, it included Ryan Scoggins on keyboards, Gaitan on upright bass, Patrick “Beans” Wheeler on drums, Chris LaForge on guitar, and Galvan on vocals. The addition of Rodriguez provided a Tejano and conjunto sound to the band.

Roberto Rodriguez III: Adding Accordion and Tejano Sound to the Pachuco Boogie Sound System Era of Los Skarnales

Born in Houston, Texas, on April 30, 1984, Rodriguez grew up in Houston’s Second Ward, where he and his family still reside. Rodriguez’s mother was born in Mexico and his father was born in Houston. As a child Rodriguez attended Tejano shows with his parents. Leonel Pulido taught Rodriguez to play the conjunto and waltzes, polkas, and schottisches of traditional música tejana on accordion. Pulido, the accordion player for Roberto Pulido y Los Clasicos, also composed music performed by other artists and groups, including David Lee Garza, the Hometown Boys, and many others. Rodriguez’s first accordion performance (as a teenager) was with the Hometown Boys, who were family friends.

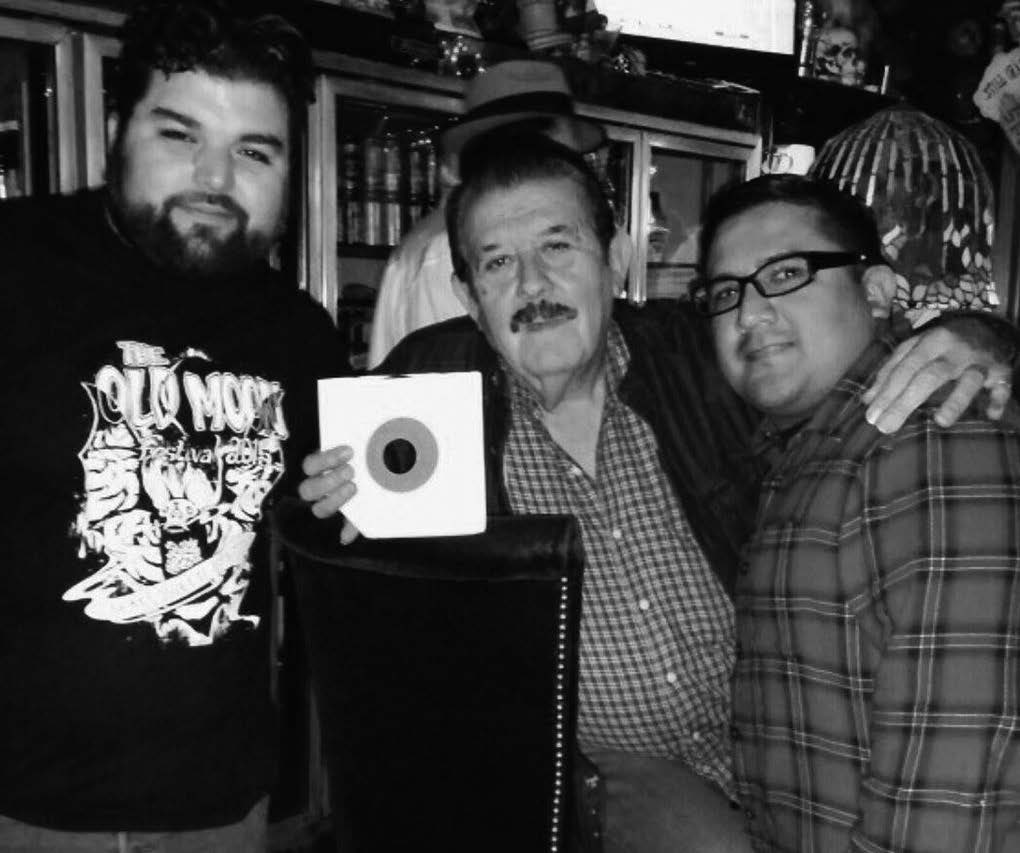

Gaitan and Rodriguez met as students at the University of Houston’s Center for Mexican American Studies at a time when Gaitan was already performing in Los Skarnales. Gaitan and Rodriguez started what was to become a close friendship and long musical partnership. Gaitan introduced Rodriguez to reggae and ska and, ultimately, to Los Skarnales.51 Rodriguez describes meeting Gaitan: “I had an AC/DC shirt, and [Gaitan] saw that, and he said, ‘Pretty cool, man. You like rock and roll?’ I was like, ‘Yeah, I like rock and roll,’ and then he found out I played accordion. He goes, ‘What? You play accordion, but you like rock.’”52

Gaitan then asked Rodriguez if he would be interested in performing in a Spanish-language ska-punk band. Rodriguez explained that he didn’t know what ska music was: “I’d heard about punk, but I wasn’t really into the music because I just grew up with Mexican-American music around me, and old classic rock and roll.”53

Adding accordion and a Tejano sound to the Pachuco Boogie Sound System lineup of Skarnales was something Galvan and Gaitan had already discussed. As Gaitan explains, “Well, we got to bring an accordion into this, man, ‘We’re doing all this stuff. We should really get a Tejano accordion player,’ and there was Robert Rodriguez.”54 Galvan loved the idea of adding accordion to the ska-punk sound of Skarnales:

And living here in Texas . . . we grew up with real good music around us, you know? I love the accordion sound from the roots Tejano music, to like looking beyond the Colombian vallenato and cumbia, you know? And to me, that accordion sound, it just brings so much . . . either a lot of joy, makes you dance, or it’s so sentimental, where it’s like if it’s a sad song, it makes you feel sad, you know? And it just hits you in the right spot.55

Without consulting the rest of Skarnales, Galvan brought Rodriguez into the band. Although accordion was not initially popular with all their fans, the Pachuco Boogie Sound System lineup has been recognized by many as one of the band’s most notable.

The inclusion of the Spanish language and pachuco style had already moved Los Skarnales in the direction of creating their “Chicano version.” The later addition of Rodriguez’s accordion and conjunto linked Skarnales more closely to música tejana and the music of the Texas Gulf Coast region; it further reflected the band members’ cultural heritage—their Texas- Mexican roots. The use of accordion differentiated Skarnales from other ska bands of the period—and their fusion of Tex-Mex music with ska-punk music was original, innovative, and novel.56

Near the end of this era, Los Skarnales released the 2005 album Pachuco Boogie Sound System, but then temporarily disbanded in 2006. However, that break yielded new opportunities for some of the band’s members.

Nick Gaitan & the Umbrella Man

During the last years of the Pachuco Boogie Sound System era, Gaitan contemplated establishing a “Texas Gulf Coast concept band . . . influenced by jazz and regional music.”57 In 2006, he embarked on his Gulf Coast band: Nick Gaitan & the Umbrella Man. Gaitan explains, “The Texas Gulf Coast concept that I was thinking about in my later days in Los Skarnales as well, the music we grew up with, the music that was around us, whether we listened to it or not, it was going in our ears. We were hearing it somehow.”58 With Umbrella Man, Gaitan moves away from ska and punk towards the music of the Texas Gulf Coast. Gaitan develops a rootsy blend of Tex-Mex (including Tejano, conjunto, and other música tejana), country (including honky tonk and rockabilly), rock and roll, swamp pop, jazz, and blues (including R&B and soul). Gaitan describes the accordion as a big part of the sound of Umbrella Man, along with steel guitar, “and, of course, drums and upright bass.”59 While Nick Gaitan & the Umbrella Man incorporates popular music and styles from outside the region, the earlier regional genres form a foundation. Gaitan tightens the focus on Houston with his lyrics.

The Texas Gulf Coast Sound in Familiar and Familial Terms

Gaitan was born in Houston, Texas, on December 11, 1979, and grew up in the East End’s Pecan Park neighborhood. Gaitan’s childhood was filled with songs from his family’s Mexican-American heritage and American popular music, including soul and rock; he was influenced by music reflecting both his cultural heritage and mainstream contemporary music:

Music was always in the house . . . but there were weekends where Mom and Dad would be cleaning the house, and they’d crank the stereo, and it would be José Alfredo Jimenez. It would be Motown tracks. It would be Marvin Gaye. It would be the Guess Who. It would be anything from the ’60s music, ’50s, and then ’40s even, but there was always music on in the house. That’s how it was a big part of my family.60

Gaitan’s maternal grandmother lived across from Guadalupe Plaza, where he and his family saw Tejano bands perform during the late ’80s and early ’90s, an era Gaitan describes as the “Tejano explosion.”61

When asked about the music of the Texas Gulf Coast region, Gaitan describes experiencing it firsthand in his community and with his family:

I’m flashing to my childhood and the sounds and sights I would hear. In our communities . . . in our area . . . from here to Galveston to wherever your family hangs out and takes you…We’re very familiar to our neighbors, our immediate neighbors, culturally speaking. Not political boundary lines, but our own cultures. We do this, they do that, but they are us. We’re never strangers to zydeco. We’re never strangers to Cajun. We’re never strangers to anybody because everybody is here in Texas. That accordion sound you hear may be Tejano, or it may be Polish, or it may be German, or it may be Czech. That’s the beauty of it. That music, along with growing up hearing zydeco and Cajun—it just sounds familiar. It sounds like the cousin of something that we grew up listening to, and it is in many ways. All of these familiar sounds that we hear, these familiar cultures. (Emphasis on “family” and “cousin” is the author’s.)62

For Gaitan and Umbrella Man, roots music is embedded in the historical music of the Texas Gulf Coast region:

To me, that’s what the Gulf Coast sounds like in many ways. That’s what I was going for. If these instruments can guide us anywhere, it’s going to keep roots music. No matter what we do, it’s going to sound like it’s got one foot in the root. I can write a song about a modern-day thing, but playing with these instruments, it’s always going to sound like home, like our region, the regional sound.”63

For Gaitan, the region’s music, family, neighborhood, and home intertwine to create an understanding of place.

Writing the Region

In Nick Gaitan & the Umbrella Man, Gaitan relies on the Gulf Coast’s existing hybrid roots sounds and employs them in his songwriting. Gaitan explains that many of these older genres have common songwriting structures and themes that make them easy to blend:

There’s blues, there’s Tejano, there’s jazz, there’s rock and roll, and there’s country, of course. All of those can make up anything of what I’m doing . . .There’s so many common areas in songwriting structure and the themes. They all fit. And to me, that’s the roots music . . . that’s the old, the music that people were playing fifty plus years ago, sixty plus now. I mean, it’s many decades, but that is what has formed rock and roll, that has formed other genres. I mean, that’s what started it all for me. That’s what I think when I consider it roots, American roots music is what I’m talking about.64

Gaitan explains that blues-based music, like Gulf Coast soul or swamp pop, can be readily integrated into his songs. Likewise, traditional Mexican songs can neatly translate into swamp pop:

Whenever you’re doing something like soul music, or you’re doing something like, say some sort of you know Texas Gulf Coast soul or blues-based music, like swamp pop, for example, mixes with some of the songs. There’s some songs in Spanish, some Mexican songs that actually sound like that or that could be easily translated into swamp pop.65

He adds that swamp pop is “one of those genres that sneaks in the country, sneaks into, you know, Mexican music. It’s everywhere, and it’s . . . a blues format. It’s like Fats Domino music being applied to any other genre around it.”66 The accordion is an essential instrument in the blending sound of Umbrella Man. It can lend a Tex-Mex feel to the music or give a Cajun feel to a country song. “There’s always a little Tex-Mex in there when we throw the accordion in, even if we’re not flat out playing a polka, just a straight-up Tejano polka. . . . They’re just going to have that flavor in there.”67

Cumbia originated in Colombia, made its way north to Mexico, and subsequently to the Texas-Mexico border communities.68 Cumbia has long been a part of Tex-Mex music, and for Gaitan, cumbia is a part of his Tex-Mex roots.69 The cumbias he performs “sound more like the Tex-Mex cumbias.”70 Gaitan is heavily influenced by Charles Mingus, who was born in Nogales, Arizona, and raised in Watts, California. Mingus embraced aspects of Latin culture and moved to Mexico in his final years. Shortly before his death, Mingus released the album Cumbia & Jazz Fusion, which blended cumbia with experimental jazz.71 Gaitan explains that jazz makes its way into the Nick Gaitan & The Umbrella Man sound more through “a laid back, sort of smoky-room-type feel.”72

While the genres situate the music within the region, the lyrics tie the music to Houston—by naming Houston, its streets, and its geography. Gaitan understands this “place naming” as part of a larger tradition, e.g., “I’m going to Kansas City.” Gaitan explains why he names places in his lyrics: “I’m mentioning Second Ward, things like this because this is where my family comes from.”73

That’s where my family ties in. It’s not only me growing up in the house and Mom and Dad playing music on the stereo; it’s my Dad, born in Laredo, raised in Houston, Clayton Homes. My Mom, born and raised in the Second Ward behind Guadalupe. They met at the Pan-America Night Club.74 They were dancing. They were young kids before my Dad went off to Vietnam. To me, these things give me pride in my roots. I think it’s just a beautiful story of my family, even before we were even thought of or were around, when my folks were dating and dancing. Pan-America Night Club is significant to me. Second Ward. East End. Just Houston in general. All of that finds its way into my music. If I’m not speaking about it directly, it’s in there. I feel there is a sound and a feeling with that.75

Nick Gaitan & the Umbrella Man Recordings

Nick Gaitan & The Umbrella Man has produced two albums; the first is Nick Gaitan & the Umbrella Man (2009). The lineup for this album includes Roberto Rodriguez III on accordion, Bart Maloney on pedal steel and guitar, Kam Franklin on vocals, Patrick Ryan on drums, and Gaitan on double bass, vocals, guitar, and bass guitar. Gaitan was the primary songwriter. Other performers on select songs included Juan Rojas (guitar and lap steel), Patrick “Beans” Wheeler (drums), Ryan Scroggins (organ), Hilary Sloan (fiddle), and Craig Kinsey (harmonica). Gaitan, Rodriguez, Wheeler, and Scroggins were previously a part of Skarnales’ Pachuco Boogie Sound System lineup.

The album Nick Gaitan & the Umbrella Man weaves together the many sounds of the Texas Gulf Coast region. Gaitan wrote or co-wrote all of the album’s songs. Many songs have a swamp pop or R&B feel, while others evoke smoky, soulful jazz or a swing reminiscent of Django Reinhardt. Some have a country or Tex-Mex feel. Most songs blend one or more of these elements.

Gaitan names places throughout this album. “Meet Me off Main” references the Main St. area by the Continental Club where Gaitan lived, worked, and performed during the recording process. “Pierce Elevated Dub” references the elevated portion of Interstate 45 that runs through downtown Houston and follows Pierce St.76 Houston is the Bayou City, and in “Neptune’s in the Bayou,” Gaitan cites “3700,” which is the address of the Continental Club, the Big Top Lounge, and studios on 3700 Main St. in Houston, including the one where Gaitan lived. This song also refers to Jensen Drive, bayous “down in Houston town,” and Sig Byrd, a journalist for the Houston Chronicle who wrote about Houston’s under-documented neighborhoods. The song “Sad, Strange, Beautiful” describes being “lost in Second Ward” and listening to the “Harrisburg trains crying in the night.”77

Gaitan’s song “I’ve Found My Weakness in You” was also later recorded by one of his three main influences, Billy Joe Shaver (the other two are Willie Nelson and Willie Dixon).78 In the first verse of the song, Gaitan describes walking from the Main Street light rail station and climbing the 26 stairs from the first floor of 3700 Main St. to his studio on the second floor. The final verse and chorus of “I’ve Found My Weakness in You” continues to reference Houston and its places:

And night falls on old 3700

That Houston skyline shines on me

Down there, they got it any way you want it

I’ve found my weakness in your . . .

Dark hair, baby, and your dark eyes too

Like the girls in Southeast Houston

Many times I’ve been a fool

I like the way you say you love me like it’s true

I’ve found my weakness in you.

Bridges and Bayous (2012), Nick Gaitan & the Umbrella Man’s second album, was recorded at SugarHill Studios, where many of Gaitan’s regional influences were first recorded. With this shorter album, honky tonk and country are intensified, with the steel guitar taking a prominent role in many of these songs. Three of the four musicians in the primary lineup, Gaitan, Rodriguez, and Maloney, performed on the first album. Songwriting credits are primarily Gaitan’s, although Rodriguez co-writes a tune and is credited for vocals. Brian Shoppell joins them on drums, vocals, and percussion.79 Songs on this album continue to name places in Houston. “El Barrio del Alacrán” is an instrumental co-written by Gaitan and Rodriguez, the title of which refers to the Spanish nickname of an old barrio torn down to make way for Highway 59 in the 1950s.80 “Hurricane Song” mentions “Travis Street” and “Houston town.”

Gaitan’s song “Juana,” which first appeared on Los Skarnales’ album Pachuco Boogie Sound System as a “big loud Brazilian samba,” returns on this album as a Tex-Mex cumbia. While writing “Juana” in the early 2000s, Gaitan was listening to a lot of Jamaican mento; he explains that mento contains a lot of tongue in cheek, “so I kind of did the same thing.”81

Nick Gaitan & the Umbrella Man Live Shows

Umbrella Man’s live shows go further than their recordings in reflecting the Texas Gulf Coast region’s sound by featuring covers of Tex-Mex standards, swamp pop, and traditional música tejana (rancheras, polkas, waltzes, and redovas). There is an emphasis on getting people to the dance floor during live performances, and these genres do support such activity. Umbrella Man’s cover of the Texas Tornados’ “A Mover El Bote” gets every “body” moving. And while Gaitan has neither recorded the Cookie and the Cupcakes’ swamp pop classic “Mathilda” nor Fender’s swamp pop/country/Tex-Mex standard “Wasted Days and Wasted Nights,” Umbrella Man regularly perform these songs for live audiences.

The Evolving Texas Gulf Coast Sound

Gaitan, Galvan, and Rodriguez continue to mix the roots music of the region with popular music. Los Skarnales still perform with Galvan at the helm, blending various roots music into their Spanish language ska-punk sound as they have for over twenty-five years.82 Rodriguez performs with many bands, including Tremoloco (since 2011); this California band, like predecessors Los Lobos and Los Super Seven, continues the tradition of blending border music and other roots sounds and calls what they perform “Gulf Coast roots.” Rodriguez founded the bands Los Pistoleros and Mas Pulpo, who blended Tex-Mex, conjunto, and punk. Gaitan currently performs as Nick Gaitan (losing the “Umbrella Man”), almost always with Rodriguez at his side and a rotating cast of musicians, including many who played with Umbrella Man or Skarnales. Rodriguez and Gaitan maintain a close working relationship and friendship. Gaitan has toured with Billy Joe Shaver and now tours with the Nikki Hill band.83 Performing with Shaver provided Gaitan the opportunity to perform with another significant influence, Willie Nelson.84

Musicians involved with Skarnales and Umbrella Man have gone on to perform with other groups. Kam Franklin, from the Houston band the Suffers, sang on and co-wrote songs on Nick Gaitan & the Umbrella Man. The Suffers define their sound as “Gulf Coast Soul” and a “mixture of the different cultures and musical styles present around the Gulf Coast and the city of Houston.”85

Other bands in the region also blend their cultural heritage music with roots and popular music. The San Antonio band Piñata Protest combines conjunto accordion with punk, and founder Alvaro Del Norte credits Galvan with supporting and inspiring him to start the group. Joaquin Abrego, drummer, composer, and singer of another San Antonio band, Los Nahuatlatos, calls their hybrid genre “Chicano fusion,” defining it as a mix of “cumbias and a little ska, a little reggae, anything with deep Latin roots.” 86

Diving Deeper into Cultural Music Heritage

Galvan, Rodriguez, and Gaitan dive deeper into their cultural music heritage and share it with the public through DJing and showcasing historical music. Galvan spins roots records, including “Ska, Cumbia, Jump Blues, Mambo, Rocksteady, Cha, Rock-A-Billy, Vallenato, Calypso, Punk & Chicano Soul” as the Pachuco Boogie Sound System.87 Together with musician and Tejano music historian Isaac Rodriguez, Roberto Rodriguez and Gaitan are uncovering, documenting, celebrating, and preserving their cultural music heritage as Tejanos, and Houstonians in particular, through a project called Tejas Got Soul.88 The project was initiated in 2014 by Gaitan and I. Rodriguez, who began DJing as Tejas Got Soul Sound System in bars within Houston’s Second Ward—particularly the D&W Lounge. They spin música tejana, focusing on Chicano soul, La Onda, and early Tejano, emphasizing Houston’s music. Through DJing, I. Rodriguez and Gaitan met musicians (or their friends or relatives) who performed or recorded the “roots” records Tejas Got Soul played. In 2017, Gaitan and I. Rodriguez met with East End community members to form a project called Tejas Got Soul to document, celebrate, and preserve the history of La Onda, Chicano Soul, and early Tejano in Houston’s East End. The project has entered a second phase, Tejas Got Soul 2, extending the geographic area to the entire Houston area and the genres to other música tejana, particularly Tejano, conjunto, and norteño.89 Robert Rodriguez joined this phase of the project as a team member.

As we have seen the older roots genres of the region blend the traditional with the popular, so too do we see this occurring in the music of Los Skarnales and, to an even greater extent, Nick Gaitan & the Umbrella Man. Like Los Lobos, Los Super Seven, and the Texas Tornados before them, these two bands reach people from outside the Mexican-American community to share the region’s music and culture. Their hybrid sounds influence popular music in Houston and beyond and continue to inform and reveal Texas’s Mexican- American experience. Los Skarnales and Nick Gaitan & the Umbrella Man inspire other regional bands to blend the region’s early music with current music to create a new Texas Gulf Coast sound. These musicians do the critical work of reflecting and expressing culture through their music and the communities they form. They transform music by blending culture and genre to create a space where people, art, and music can mix.

Notes

- Andy Bradley and Roger Wood, House of Hits: the Story of Gold Star/ SugarHill Recording Studio (Austin: University of Austin Press, 2010), 33, xii; Roger Wood and Ray Cano, Jr., “SugarHill Recording Studio,” The Handbook of Texas Online, Texas State Historical Association, (accessed October 19, 2020). Notable Houston studios included Audio Company of America (ACA) and Gold Star (which eventually became SugarHill). Bill Holford opened ACA in 1950. Bill Quinn opened Quinn Recording in 1941 and changed the name to Gold Star in 1950. The studio was called International Artists Record Company Studios in 1968 and 1969, and Huey Meaux purchased and renamed it SugarHill in 1971. It remains the longest operating recording studio in Texas.

- Transcripts and recordings of these interviews are available online at the University of Houston Libraries institutional repository.

- While offering a broad overview of the roots music in Houston and the region (primarily from the 1920s through the 1970s), this section also provides the context for understanding the distinctive Houston roots music of Los Skarnales and Nick Gaitan & the Umbrella Man. This section is predominantly focused on Houston, but much of the genre creation discussed was similarly occurring across the Texas Gulf Coast region.

- Interstate 10 (I-10) runs east and west through the city, from Lafayette through the heart of the Golden Triangle (the three-city area of Beaumont, Port Arthur, and Orange) to Houston, onto San Antonio, and beyond.

- Guadalupe San Miguel Jr., Tejano Proud: Tex-Mex Music in the Twentieth Century (College Station: Texas A&M Press, 2002), 3-4. Música tejana is an umbrella term for Texas-Mexican music that includes traditional music such as canciones Mexicana, corridos, boleros, rancheras, and huapangos as well as more recent genres including conjunto, Chicano soul, and Tejano. San Miguel explains that música tejana is Texas-Mexican music that is “not specific to any one time period” and for his book he defines it as “all the musical genres, forms, and styles that have existed in the Tejano community since at least the nineteenth century.”

- Steve McVicker quoted in Tyina L. Steptoe, Houston Bound: Culture and Color in Jim Crow City (Oakland: University of California Press, 2015), 208.

- Jonathan Gill, “Leadbelly (Ledbetter, Hudson William),” Encyclopedia of African-American Culture and History, 1996 (accessed May 3, 2021).

- Steptoe, Houston Bound, 159. Larkin performed with Gilbert Jacquet, Illinois Jacquet’s father. Gilbert Jacquet was a Louisiana Creole from the Fifth Ward and Larkin was from the Third Ward. For detailed information on the Chitlin’ Circuit, the Milt Larkin Band, and Don Robey’s role in both, see Preston Lauterbach, The Chitlin’ Circuit: and the Road to Rock ‘n’ Roll (New York: W. W. Norton, 2011), 98-101.

- Steptoe, Houston Bound, 160-161, 181-182. During this time, the battles of the bands between Phillis Wheatley (Fifth Ward) and Jack Yates (Third Ward) high schools were fiercely competitive, and the Texas tenor sound developed as a way to be heard above the rest of the band. Alex La Rotta, “Talk to Me: The History of San Antonio’s West Side Sound,” Journal of Texas Music History, 13 (2013): 18. With the Texas tenor sound, the horns honked on the low notes and squeaked on the high ones. In an interview, musician Spot Barnett described how the Texas tenor sound developed in San Antonio similarly to Houston, through high school band competitions.

- Dave Oliphant, Jazz Mavericks of the Lone Star State (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2007), 71-72. In 1942, Illinois Jacquet joined the Lionel Hampton Orchestra and left later that year to join Cab Calloway’s band. Jacquet was member of the Count Basie Orchestra from 1945 to 1946. Steptoe, Houston Bound, 180. Jacquet’s performance of “Flying Home” for Lionel Hampton’s band was one of the first recordings of the Texas tenor sound. Stephen G. Williams and Kharen Monsho, “Arnett Cleophus Cobb (1918–1989),”Handbook of Texas History Online, Texas State Historical Association (accessed November 3, 2020). Cobb replaced Jacquet in Hampton’s band in 1942 and also performed with Jimmie Lunceford, Count Basie. Jason Head, “Vinson, Eddie [Cleanhead] (1917–1988),” Handbook of Texas History Online, Texas State Historical Association (accessed November 3, 2020). In 1941, “Cleanhead” joined Cootie Williams’s orchestra.

- La Rotta, “Talk to Me,” 18.

- Bradley and Wood, House of Hits, 23.

- Roger Wood, photography by James Fraher, Down in Houston: Bayou City Blues (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2003), 49.

- Kevin Coffey, Cliff Bruner and His Texas Wanderers (Germany: Bear Family Records, 1997), liner notes, 1. The Texas Wanderers included Lee Bell on electric guitar, Bob Dunn on electric steel guitar, Leo Raley on mandolin, J.R. Chatwell on fiddle, Dickie McBride on guitar and vocals, and Moon Mullican on vocals and piano. As Kevin Coffey explains, “Bruner’s fiddling epitomized Texas Swing: a rural tradition brought to the city and melded with myriad influences to produce something not so much new but identifiably different that anything that came before.”

- Johnny Bush with Rick Mitchell, Whiskey River (Take My Mind): The Story of Texas Honky-Tonk: (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2007), 173. Johnny Bush’s uncle was Jerry Jericho, a Houstonian and a musician who recorded regional hits. Bush explains that the honky tonk fiddler sound was influenced by the simpler sound of the Cajun fiddle rather than the showy sound of the Appalachian bluegrass fiddle, which was influential in other country music.

- Bradley and Wood, House of Hits, 79-80. Pappy Daily, Jones’s manager, thought the song was not country enough and passed on it and Nelson. For an excellent source of information about Pappy Daily’s early career in Houston and the artists he recorded at Gold Star, see Nathan Gibson, The Starday Story: The House Country Music Built (Jackson: University of Mississippi, 2011), 3-48.

- Steptoe, Houston Bound, 2; Diana J. Kleiner and Ron Bass, “Frenchtown, Houston,” Handbook of Texas History Online, Texas State Historical Association (accessed June, 6, 2020); Shane K. Bernard, Swamp Pop: Cajun and Creole Rhythm and Blues (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1996), 23. Cajuns and Creoles have long looked for work in Houston and the Golden Triangle area of Beaumont, Orange, and Port Arthur, which are rich with industrial work. Both Creole and Cajun music are accordion-based genres, but Cajun music also features fiddles.

- Roger Wood, photography by James Fraher, Texas Zydeco (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2006), p. 6-8; Kleiner and Bass,“Frenchtown, Houston,” ;Steptoe, Houston Bound, 203-204. Cultural and musical syncretism that occurred in Houston’s Fifth Ward was key to the development of zydeco. Louisiana Catholic Creoles from “Frenchtown” (established in 1922) lived alongside and were influenced by protestant Black Texans. Bradley, House of Hits, 27.

- Steptoe, Houston Bound, 198-199; Wood, Texas Zydeco, 154; Wood and Fraher, Down in Houston, 48. The French phrase “les haricots sont pas salés” was frequently used in la-la music; it translates to “the beans are not salty” and is a metaphor for hard times. The name for the burgeoning zydeco music became associated with “les haricots” as well as many other forms and spellings of the term, such as “zarico” and “zologo.” The spelling was solidified when Chris Strachwitz of Arhoolie Records recorded an album for Clifton Chenier (one of the key musicians in creating and popularizing this sound) at Gold Star in 1965 and Houston music historian/folklorist Mack McCormick suggested “zydeco.”

- Bernard, Swamp Pop, 23. The Golden Triangle area in the South Louisiana region is known to Cajuns and Creoles as “Lapland,” “where Cajun country laps over into southeast Texas.”

- Bradley and Wood, House of Hits, 21. Chotes’s “Jole Blon” hit #4 on Billboard’s Most Played Jukebox Folk Records chart and was the first and only Cajun song ever to make Billboard’s top 5 in any category.

- Coffey, Cliff Bruner and His Texas Wanderers, 1.

- Bernard, Swamp Pop, 6. Preston’s “Running Bear” is also considered to be a swamp pop classic.

- Bradley and Wood, House of Hits, 72-77.

- Bernard, Swamp Pop, 19-20. Shane K. Bernard, “Swamp Pop,” The New Encyclopedia of Southern Culture, Volume 12: Music, edited by Bill C. Malone (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2009), 365.

- Ibid., 63. Laurie E. Jasinski and Jennifer Cobb, “Heuy P. Meaux,” The Handbook of Texas Online, Texas State Historical Association. In his barbershop in 1959, Huey Meaux produced his first hit—"Jivin' Gene" Gene Bourgeois’s swamp pop classic “Breaking Up is Hard to Do.” Soon thereafter, Meaux’s Crazy Cajun Enterprise was on its way to producing and recording a diversity of genres from across the Texas Gulf Coast, including Chicano soul, rock and roll, rhythm and blues, Cajun, swamp pop, and blues. Amongst others, Meaux recorded Sunny and the Sunliners’ 1962 hit “Talk to Me,” Sir Douglas Quintet’s 1965 hit “She’s About a Mover” (featuring both Doug Sahm and Augie Myers), and Beaumont-born Barbara Lynn’s 1966 hit “You’ll Lose a Good Thing.” Meaux recorded Freddy Fender’s 1974 comeback hit “When the Last Teardrop Falls” in Spanish and English.

- Ibid., 27.

- Ibid., 60, 64. Freddy Fender was born in San Benito near the Texas- Mexico border but lived in South Louisiana during a formative part of his early career.

- Between 1920 and 1940, Houston’s ethnic Mexican population grew from around six thousand to twenty thousand. Many of these newcomers settled in Houston’s Second Ward. Steptoe, Houston Bound, 4.

- Steptoe, Houston Bound, 175-176. In 1934, Mendoza first recorded the song for which she is best known, “Mal Hombre,” for RCA Blue Bird in San Antonio. Patoski, Joe Nick, “Uno, Dos, One, Two, Tres, Cuatro,” Journal of Texas Music History, 1, no. 1 (2011): 14. Patoski identifies Mendoza as the “first Tejana singing star with a string of hit recordings, including her sizzling put-down of bad men, ‘Mal Hombre,’ that sold across the United States and Latin America.”

- Ibid., 175. Manuel Peña, The Texas-Mexican Conjunto (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1985), 9.

- Ibid., 176.

- Manuel Peña, “Texas-Mexican Conjunto,” Smithsonian Institution (accessed December 25, 2020). Manuel Peña describes conjunto as the “everyday music of working-class Texas Mexicans and Mexicans,” citing accordionist Paulino Bernal who refers to the division between fans of the two genres: “he who liked the orquesta hated the conjunto.”

- La Mafia’s prolific touring and recording earned them five Grammy Awards. Manuel Peña, Música Tejana: The Cultural Economy of Artistic Transformation (College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 1999). Peña credits La Mafia with being the first Tejano group to earn “large- scale international success” and adds, “If Mazz represents the Tejano entry into the world of the balada, then La Mafia represents the cumbia” (200- 201).

- Steptoe, Houston Bound, 178. Tyina Steptoe also notes earlier influences of Mexican performers on Black musicians in Texas. Steptoe cites scholar Gaye Theresa Johnson who calls Texas a musical borderland where Mexican music influenced Black music. For example, Huddie Ledbetter, better known as “Lead Belly,” learned bajo sexto from ethnic Mexicans during his travels through the state with Blind Lemon Jefferson “and purchased his famous 12-stringed instrument from a Mexican vendor.”

- Ibid., 205.

- Ibid., 219.

- La Rotta, “Talk to Me,” 18. Influenced by San Antonio’s West Side Sound, these performers combined elements of Texas-Mexican music with blues, R&B, and rock and roll music to create a genre that has substantially impacted musicians throughout Texas. On the West Side Sound, Alex LaRotta states, “Contrary to its name, the ‘West Side Sound’ did not actually originate on the West Side of San Antonio. Nor, for that matter, is it a singular ‘sound’ that can be easily defined or categorized. In fact, the term ‘West Side Sound’ was not widely used until San Antonio musician Doug Sahm applied it to his band, the West Side Horns, on his 1983 album, The West Side Sound Rolls Again. Since then, journalists, music fans, and even Sahm himself have retrofitted the term to describe a particular style that emerged from San Antonio and the greater South Texas region beginning in the 1950s and continuing into the early twenty-first century.” Patoski, “Uno, Dos, One, Two, Tres, Cuatro,” 3. Joe Nick Patoski identifies Doug Sahm as an originator of Tex-Mex Rock and Roll: “[N]o single performer grasped the atmospherics of Tex-Mex quite like Doug Sahm, a white boy from San Antonio who was a child prodigy on the steel guitar and whose life changed when he saw Freddy Fender perform at a San Antonio drive-in movie theater in 1958.”

- Tejano musicians Rick Treviño (Austin) and Ruben Ramos (Sugar Land) are the only musicians who performed on all three albums. Tex-Mex performers Flaco Jimenez, Augie Myers, and Freddy Fender from the Texas Tornados recorded with the collective as did many of the Los Lobos musicians. The Arizona-based Tex-Mex band Calexico was featured on the third album. Max Baca of Texmaniacs performed on the last two albums. Other performers included Willy “Wil-Dog” Abers of Ozomatli, Raul Malo of the Mavericks, and Texas singer-songwriters Joe Ely, Lyle Lovett, and Rodney Crowell (Crowell and Lovett both with close ties to Houston), as well as many other performers including Clarence “Gatemouth” Brown.

- Traber, Daniel S., “Pick It Up! Pick It Up!: The Transnational Localism of Ska,” Popular Music and Society 36, no. 1, (2013): 1-18. Ska music moved from Jamaica to England (first wave) and evolved into England’s two-tone sound of the 1970s and ‘80s (second wave). Traber’s article provides a strong overview of the history of ska and its three waves before focusing on Los Skarnales, whom Traber describes as “a Chicano-based ska band in Houston who meld diverse forms, including the local flavors of their neighborhood.”

- Felipe Galvan in discussion with the author, May 2, 2018, approximate timestamp: 39:42. Los Skarnales have been influential in Mexico and were already popular there before their first show in Mexico because of piratería (in this case the piracy consisted of widespread distribution of bootlegged Los Skarnales cassettes). Los Skarnales often perform there to this day.

- Felipe Galvan in discussion with the author, May 2, 2018, approximate timestamp: 27:20, 28:10, available online: https://uh-ir.tdl.org/ handle/10657/7299.

- Felipe Galvan in discussion with the author, May 2, 2018, approximate timestamp: 11:20.

- Felipe Galvan in discussion with the author, May 2, 2018, approximate timestamp: 1:41. Galvan’s mother performed regional Mexican music and his father performed in a rock and roll band. They met as performers in a traveling music and variety show.

- Steven Loza, “Chicano/Latino Music, from the Southwest to the Northeast,” Ethnic and Border Music: a Regional Exploration, edited by Norm Cohen (Westport, Connecticut, Greenwood Press, 2007), 72-73.

- Lopez, Tara ,“!Vamos pa’l Chuco!: Punk Rock, Power, and Memory in El Paso, Texas,” Journal of Texas Music History 20, (2020): 30.

- Romeo Guzmán, “Tin Tan (1915-1973),” Iconic Mexico: An Encyclopedia from Acapulco to Zócalo, Eric Zolov, ed., (Santa Barbara, California: ABC CLIO, 2015), 612-616. Pachuco was initially almost exclusively a Mexican-American culture; however, Tin Tan brought this culture first to Mexico and then to the rest of the world with his extraordinarily popular movies.

- Felipe Galvan in discussion with the author, May 2, 2018, approximate timestamp: 13:50.

- Felipe Galvan in discussion with the author, May 2, 2018, approximate timestamp: 13:16.

- Felipe Galvan in discussion with the author, May 2, 2018, approximate timestamp: 15:58.

- Rodriguez in discussion with the author, “Interview 1,” June, 21, 2015, approximate timestamp: 28:55.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Gaitan in discussion with the author, “Interview 1,” August 10, 2015, approximate timestamp: 29:35.

- Felipe Galvan in discussion with the author, May 2, 2018, approximate timestamp: 29:03.

- Patoski, “Uno, Dos, One, Two, Tres, Cuatro,”1-3. Patoski uses Sam the Sham’s song “Wooley Bully,” in particular its introduction (“Uno, Dos, One, Two, Tres, Cuatro”) to illustrate the blending of Tex with Mex, and Spanish with English, that would have been “natural” to Sam Samudio, who grew up in the barrios of East Dallas. Patoski positions Los Skarnales within the tradition of Tex-Mex music, along with the Sir Douglas Quartet, Doug Sahm, Freddy Fender, Sunny and the Sunliners, and others—as current musicians continuing the tradition of Tex-Mex blending.

- Gaitan in discussion with the author, “Interview 1,”August 9, 2015, approximate timestamp: 30:45.

- Gaitan in discussion with the author, “Interview 1,”August 9, 2015, approximate timestamp: 32:32.

- Gaitan in discussion with the author, “Interview 1,”August 9, 2015, approximate timestamp: 35:00.

- Gaitan in discussion with the author, “Interview 1,” August 10, 2015, approximate timestamp: 1:35.

- Gaitan in discussion with the author, “Interview 1,” August 10, 2015, approximate timestamp: 2:45.

- Gaitan in discussion with the author, “Interview 1,” August 9, 2015, approximate timestamp: 33:20.

- Gaitan in discussion with the author, “Interview 1,” August 9, 2015, approximate timestamp: 35:00.

- Gaitan in discussion with the author, “Interview 2,” September 21, 2017, approximate timestamp: 1:15:01.

- Gaitan in discussion with the author, “Interview 2,” September 29, 2017, approximate timestamp: 1:48.

- Gaitan in discussion with the author, “Interview 2,” September 29, 2017, approximate timestamp: 21:05.

- Gaitan in discussion with the author, “Interview 1,” August 10, 2015, approximate timestamp: 37:15.

- Lea Ramsdell, “Transnational Trajectories of Columbian Cumbia,” Towston University Journal of International Affairs, spring 2020, 44-50, https://wp.towson.edu/iajournal/journal-issues/2010-2019/spring-2020/ transnational-cumbia/ (accessed online May 15, 2021). The term “cumbia” appeared in the late 1800s though the genre that emerged in Afrodescendent communities had been developing since the first part of the century (45). Cumbia made its way north and “big band cumbia landed with a splash in Mexico in the 1940s” (47). Ramsdell explains, “While the urban elites were the first to take to the genre, soon the cumbia . . . infiltrate[d] the accordion-infused norteño music that was a mainstay of the soundscape of the borderlands” (47).

- San Miguel, Jr., Guadalupe, “Música Tejana: More than Conjuntos and Orquestas” (NACCS Annual Conference Procedings, 2001: 28th Annual: Beginning a New Millenium, Tucson, AZ., 215-224). La Onda, which developed in the mid 1960s, differed from orquesta in that it had a more streamlined bass line; the cha-cha-chas, danzones, boleros, and fox trots were replaced with the cumbia. When discussing the revival of conjunto in the 1990s, San Miguel notes that both Tejano and conjuntos norteños “changed the traditional core of this music and increased the percentage of cumbias and baladas in their repertoire” (216). Manuel Peña, Música Tejana: the Cultural Economy of Artistic Transformation (College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 1999). Peña identifies the primary elements of post-Chicano-era Tejano music as polka-ranchera, balada, and cumbia often interlaced with other genres such as reggae or rap (185).

- Gaitan in discussion with the author, “Interview 1,” August 10, 2015, approximate timestamp: 38:48. “The other genres come in like cumbia, which of course is just a branch off of our Tex-Mex roots. Our cumbias sound more like the Tex-Mex cumbias.”

- Luis Alvarez, “The L.A. Scene: Teaching Race and Popular Music in the 1950s,” OAH Magazine of History 26, no. 4 (2012): 17-20. In the 1950s Southern California musicians turned to Mexico for inspiration. Alvarez provides Mingus as an example: “Bassist Charles Mingus, for instance, who was born along the US-Mexico border in Nogales, Arizona, grew up in the Watts section just a few blocks from Gil Bernal. He identified with black, white, Indian, Asian, and Mexican heritage and, as cultural critic Josh Kun notes, thought of himself as a ‘half-schitt-colored n****r.’ His jazz fused musical forms from across the Americas, blending Mexican traditions, Cuban mambo, Puerto Rican bomba, and Colombian cumbia. Mingus’s 1957 recording of New Tijuana Moods sketched his interpretations of border living and marked his ongoing engagement with life, politics, and sounds south of the international boundary” (17).

- Nick Gaitan in discussion with the author, “Interview 1,” August 9, 2015, approximate timestamp: 40:11. “I would say some of my stuff even lends itself to jazz a little bit, but not any specific type. Just kind of a laid back sort of smoky room-type feel, more atmosphere than anything. I call it jazz because I can’t think of another word for it.” Gaitan in discussion with the author, “Interview 1,” August 9, 2015, approximate timestamp: 16:43. Gaitan had long been influenced by jazz and taught himself to play stand-up bass by listening to jazz performances: “I would go walk to Brazil coffee shop on Westheimer on Thursday nights and sit at the table, the closest I could get to the bass player and watch his action. Watch his hands. Watch everything. Listen, you know. That’s how I started to learn. I was a library worker at the time, so I was able to pick a lot of Charles Mingus and other different jazz artists, but Charles Mingus was a big influence on me."

- Gaitan in discussion with the author, “Interview 1,” August 10, 2015, approximate timestamp: 1:10:15.

- The Pan-America is commonly called either “Ballroom” or “Nightclub,” and the spelling on the marquee was “Nite Club.” Lyndsey Scovil Dove, “For the Love of Live Music: A Sampling of Houston Music Venues, 1930s to 1970s,” Houston History, University of Houston Center for Public History, November 20, 2013, 23-24. “On the north side of town, the Pan-America Ballroom was the first music venue in the city to have regular performances by Chicano and Tejano artists during the 1960s and 1970s. Located at 1705 North Main, the Pan-America had a capacity of 2,500, and patrons packed the hall to dance the night away while listening to bands from the United States, like Isidro Lopez and Little Joe, and from Mexico, such as Carlos Campos and Mike Laure.”

- Gaitan in discussion with the author, “Interview 1,” August 10, 2015, approximate timestamp: 1:11:27.

- “Pierce Elevated Dub” sounds like a stripped down instrumental dub song, but unlike many dub songs, it is not based on a poular song but is an original composition.

- Jensen Dr. and Harrisburg St. run through Houston’s East End.

- Gaitan in discussion with the author, “Interview 1,” August 10, 2015, approximate timestamp: 41:58. “I played this song. Billy loved it. Billy loved it. Then when we got on the bus and we’re leaving the gig, he says, ‘When did you write that song?’ I said, ‘I wrote the song like two weeks ago.’ He said, ‘That’s a good song. What are you calling it?’ I said, ‘I’m calling it “I Found My Weakness in You.” I don’t know. I said, ‘I’m calling it “Dark Eyes.”’ He says, ‘But what’s that thing you said?’ I said, ‘I found my weakness in you.’ He says, ‘You should call it that.’ He says, ‘I don’t want none of it. Just call it that. I would call it that if I wrote that song.’ He goes, ‘I think I wrote that song.’ Joking around with me. We laughed. He talked about the song for a while. If it made an impression on him, I felt like I was doing the right thing because he’s one of the best songwriters ever. Period.”

- The recording also included Jose (Chapy) Luna on percussion and Grover Gill on piano on select tracks.

- Highway 59 also recently established as part of an Interstate corridor to be known as I-69. “Historical Houston Latino Neighborhood, El Barrio Del Alacran, to Get Texas Historical Marker,” The Venture, August 1, 2013 (accessed August 6, 2020).

- Gaitan, text message to author, September 21, 2020.

- Other than the short break that Los Skarnales took in 2006, the band has performed with a revolving cast of musicians continuously to date. Jose Rodriguez returned after the band’s hiatus, and the size of the band grew and again includes horns. Jesse Sendejas Jr.,“Piñata Protest Salutes Los Skarnales on Its Silver Anniversary,” Houston Press, December 27, 2019 (accessed June, 15, 2020). The band celebrated their 25th anniversary on December 27, 2019 with a show that included many previous members. Tex-Mex punk band Piñata Protest, whose accordion player Alvaro Del Norte credits Galvan and Los Skarnales as inspiring him to start his own band, also performed.

- Gaitan in discussion with the author, “Interview 1,” August 10, 2015, approximate timestamp: 49:27. “I got turned on to Billy Joe Shaver years before I played with him. The magnitude of the effect and the depth of the understanding or just the learning of it, the process, couldn’t be deeper than you being his bass player, though. Riding alongside him, hearing him just when we talk, when we play, watching him do gigs that you thought he was feeling bad at, but he never puts on a bad show. That guy has been an influence hands-on as far as being in his band, running with him across the country, running with him across the ocean. He’s 75 and he’s got 30-somethings and 40-somethings, and he’s keeping up right with them. Learning from him, that’s strength, that’s persistence, that’s being stubborn in the face of that dream, but it’s also being a great songwriter. You can’t fake that. You can’t fake that.”

- Gaitan in discussion with the author, “Interview 1,” August 10, 2015, approximate timestamp: 1:12:40. When asked about which experience had the biggest impact on him, Gaitan responsed, “The freshest one for me was the night of December 17 last year. I was on The Late Show with David Letterman. I was up there with Willie Nelson and Billy Joe Shaver. I’ve always been the type of kid to bring my report cards home to my parents and hand them over just to make them proud. This is cool. So my Dad, I got to share that with him. Let me get straight. He passed a month ago. . . . He got to see me on TV with Willie Nelson. That was a big deal. All of these major stepping stones, all of these major events they were so significant. That one was just the home run. It was the last big thing he saw me do He watched it live, and we enjoyed it. That was December. We enjoyed him for another seven months after that.”

- The Suffers, interview by Robin Cook, “The Suffers interview,” The Blot Magazine, March 18, 2015 (accessed March 3, 2019). The Suffers describe their Texas Gulf Coast Soul and their biggest influences as their environment (the port city of Houston) and the musical styles they encounter there including blues, soul, country, Caribbean music, Cajun, hip-hop, and others.

- William Michael Smith, “San Antonio’s Los Nahuatlatos Keep Their Chicano Fusion in Motion,” Houston Press, October 24, 2019.

- Felipe Galvan in discussion with the author, May, 2, 2018, approximate timestamp 59:43. On the roots music, including honky tonk and Western swing, that he spins, Galvan says, “I like to do strictly roots. Roots Jamaican music, roots American music, everything from Western swing to jump blues to rockabilly to soul to surf I’m a big country and western fan, too, you know? I still try to put in some Hank Snow or like Ernest Tubb, you know, Bob Wills. I put some Western swing there all the time. So, yeah, it’s mainly roots music, you know?”

- Isaac Rodriguez in discussion with the author, April 22, 2017 and September, 21, 2017. Isaac Rodriguez was also interviewed as part of the research for this article. Isaac is a multi-generation, proud Tejano. His interviews reveal a deep understanding of música tejana, and especially La Onda, Chicano soul, and Tejano.

- Isaac Rodriguez, Nick Gaitan, Pat Jasper, and Angel Quesada were Tejas Got Soul team members and are currently Tejas Got Soul 2 team members. Roberto Rodriguez III joined Tejas Got Soul 2 as a team member. The author was a Tejas Got Soul team member and currently works with the team to archive their project documentation at the University of Houston Libraries Special Collections.