JTMH Volume 21 | War News Blues

War News Blues: Lightnin’ Hopkins, World War II, Korea, and Vietnam

Joe W. Specht 1

Lightnin' Hopkins is undoubtedly among the elite of twentieth-century blues musicians. For folklorist Mack McCormick, who produced and managed Hopkins for a time, “The essence of Lightnin’s art is a special form of autobiography. His songs all have their basis in actual experience which he captures with dramatic gravity and a gift for succinct detail.”2 Or as roots music historian and discographer Tony Russell proffers, “Lightnin’ Hopkins filed stark reports from the war-zone of everyday life in the black Houston of the late 40s; stories of shotguns and jailhouses, no friends and no mail; the Short Haired Woman and the Big Mama Jump.”3

That said, if Hopkins’s reputation rests in large part on his compositions of personal introspection, he also framed songs that touch on national events; for example, the Project Mercury space program (“Happy Blues for John Glenn”), tropical storms (“Hurricane Betsy”), and floods (“California Mudslide”). Then there are the commentaries associated with America’s involvement in international “war-zones,” if you will: World War II, Korea, the Cold War, and Vietnam. Although Hopkins did not serve in the armed forces, over a span of twenty years, he wrote and recorded eight songs ranging from “European Blues” in 1949 to “Please Settle in Viet Nam” in 1969. These compositions, which speak to the issues of Lightnin’s day through his own distinctive lens, are the focus of this article.

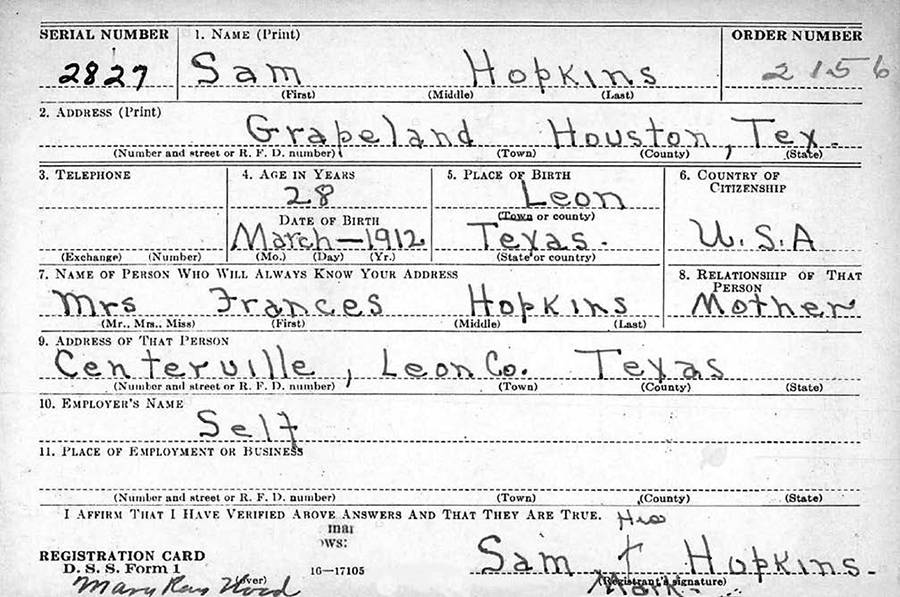

Sam “Lightnin’” Hopkins was born in 1912 on a farm outside of Centerville in Leon County.4 He made his first guitar out of a cigar box when he was eight years old and furthered his musical education by partnering in his late teens with an older cousin, Alger “Texas” Alexander, who had been recording since 1927.5 The pair wandered around the east central part of the state playing house parties, picnics, and socials in places like Jewell, Buffalo, and Crockett. During the 1930s, Sam also sharecropped at times, while working odd jobs. He was living in Grapeland in Houston County in 1940. It is still unclear when Hopkins permanently moved to Houston and the Third Ward, but he had certainly established himself in the Bayou City by the end of World War II. In an often-cited December 2, 1964, interview with Samuel Charters, Lightnin’ explains, “The first time . . . was 1934, but I didn’t stay . . . so I goes back again around ’38 or ’39, and I stuck around there for a while playing up and down [Dowling] street.”6

By 1946, Hopkins had made a name for himself in the Third Ward busking on Dowling Street. He caught the attention of Lola Ann Cullum, a talent scout with connections to Aladdin Records in Los Angeles. Cullum secured a contract for Hopkins, and it is here in the City of Angels that he acquired the moniker “Lightnin’” (the record company teamed him with pianist and fellow Houstonian Wilson “Thunder” Smith and decided to promote the two as “Thunder” and “Lightnin’”).7

At the initial Aladdin session on November 8, 1946, Hopkins and Smith recorded “Katie Mae Blues” (Aladdin 167).8 The song is Lightnin’s homage to a “good girl . . . she don’t run around at night . . . Katie Mae will treat you right.” And it includes the memorable line, “You know she walks just like/She got oil wells in her backyard.” “Katie Mae Blues” earned more than its share of nickels in jukeboxes throughout Texas and the Southwest.9

Back in Houston, Hopkins began an affiliation with Bill Quinn, the pioneering studio engineer and owner of Gold Star Records. At the time, Quinn was recording both country and blues singers at his 3104 Telephone Road studio.10 Although he was contractually obligated to Aladdin Records, Lightnin’ also signed on with Quinn and Gold Star. The practice of recording for whomever he chose, whenever he wanted, and usually requiring only a flat rate per song (with payment in cash) was a modus operandi that Hopkins followed throughout his career.11

Quinn’s Telephone Road studio was located in southeastern Houston right next to the Third Ward, making it easy for Lightnin’ to pop-in, often unannounced, and lay down a couple of tracks when he was short on loose change.12 And, in contrast to his unamplified Aladdin session, Hopkins brought along his electric guitar, which heralded a new and grittier sound for the bluesman. “Short Haired Woman” (Gold Star 3131), his initial Gold Star outing, quickly became a jukebox favorite and another of his signature songs.13 Indeed, the professional association with Quinn in the studio (he recorded over 100 sides with Quinn) laid the groundwork for Hopkins to assume a national presence among African American listeners with later releases on various labels, including Sitting In With, Jax, Mercury, Decca, and Herald.14

Hopkins waxed “European Blues” (Gold Star 665), the first of his war-related observations, at Quinn’s studio in October 1949.15 Just Lightnin’ and his electric guitar. The memories of World War II were still fresh. African Americans had actively served in the Army and Navy, albeit in segregated units and largely non-combat roles: stevedores, ammunition handlers, truck drivers, boiler room firemen, stewards, cooks, and, in the moment, also transcending those roles, as Waco’s own Doris Miller showed at Pearl Harbor.16

The Selective Training and Service Act, which became law on September 15, 1940, required all males between the ages of 21 and 35 to register for the draft.17 The twenty-eight-year-old Hopkins, still living in Grapeland, registered on October 16, 1940.18 Sam would relate to Mack McCormick that he later received his draft notice, but prior to reporting for active duty, he was seriously injured in a dispute over his winnings in a crap game.

Took that ol’ boy’s money. That fool waited outside for me and when I come out he slipped a grizzly knife right in close to my heart. That took care of the Army. Never was in the war . . . got stabbed and that took care of that. I laid up in the Jeff Davis hospital and made a song about all the men going across the water, all the women staying at home with me.19

Even though the chronology fits, Hopkins biographer Alan Govenar is less convinced that the incident occurred, speculating that, because of Hopkins’s police arrest record, “if he had indeed served time in jail or on a chain gang, he would never have been drafted in the first place. It’s likely he invented the stabbing story during the 1940s.”20

In any case, in “European Blues,” Hopkins speaks to the totality of the war–“Yeah, you know the people raidin’ in Europe/They’re raidin’ on both sea, land, and air”–while candidly acknowledging,

You know my girlfriend got a boyfriend in Europe

That fool’s already crossed the sea

You know I don’t hate it so bad

That’s a better break for me.

Here Hopkins is also tapping into the saga of Jody, “the mythical backdoor man who has his way with women” when a boyfriend or husband is absent.21 But far from being illusory, the presence of the wily predator was, in fact, a reality in many a couple’s lives. And references to Jody, or “Jody calls,” were regularly mixed into the marching cadences, the call and response chants that were part of an enlisted man’s daily routine: “Ain’t no use in going home/Jody’s got your girl and gone/Ain’t no use in feeling blue/Jody’s got your sister, too.”22

Jody songs contemporaneous with Hopkins’s “European Blues” include Sonny Thompson’s 1951 “Uncle Sam Blues” (King 4431) with vocalist Jessie Edward’s plea, “Uncle Sam, Uncle Sam, please find somethin’ for Jody to do/Why don’t you send him over there to stop some bullets, too?”23

In the last verse of “European Blues,” Hopkins also makes a passing reference to the draft: “Yes, I got a letter this morning/ Sayin’ practically all the boys got to go.” And while the Selective Training and Service Act included provisions against discrimination based on race or color, the War Department continued to affirm that African Americans should serve in all-Black units in the Army and Navy usually under the command of white officers, while initially at least being excluded entirely from the Air Corps, Marines, and Coast Guard.24

Less than nine months after the release of “European Blues,” fighting broke out on the Korean peninsula when North Korea invaded the South on June 15, 1950. Hopkins followed with “War News Blues,” again recorded in the Quinn studio most likely in late 1950.25 Here the bluesman captures a sense of fear and dread in the air with the potential use of the atomic bomb hovering overhead.

You may turn your radio on soon in the morning, sad news every day

Yes, you know I got a warning trouble is on its way.

Poor children running, crying, “Whoa, mama, mama, now what shall we do?”

“Yes,” she said, “You’d better pray, children, same thing is happening to mama too.”

Certainly by this time and after the Chinese intervention in the conflict, both General Douglas MacArthur, commander of United Nations forces, and President Harry S. Truman had publicly commented on the possibility of dropping an A-bomb.26 With the specter of nuclear conflagration looming, the singer can offer only the simplest of solutions.

I’m gonna dig me a hole this morning, dig it deep down in the ground

So if it should happen to drop a bomb around Somewhere

I can’t hear the echo when it sounds.

Arthur “Big Boy” Crudup expressed a similar notion the next year in “I’m Gonna Dig Myself a Hole” (RCA Victor 22/50-0141): “I’m gonna dig myself a hole, move my baby down in the ground/You know, when I come out, there won’t be no wars around.”27

“War News Blues,” replete with his familiar guitar riffs, was one of twenty Hopkins titles Quinn sold to the Bihari Brothers, owners of Modern Records in Los Angeles, after Quinn quit the record-selling business in 1951. However, the song remained unreleased until 1970 when it appeared on the album A Legend in His Own Time (Kent KST 9008).28

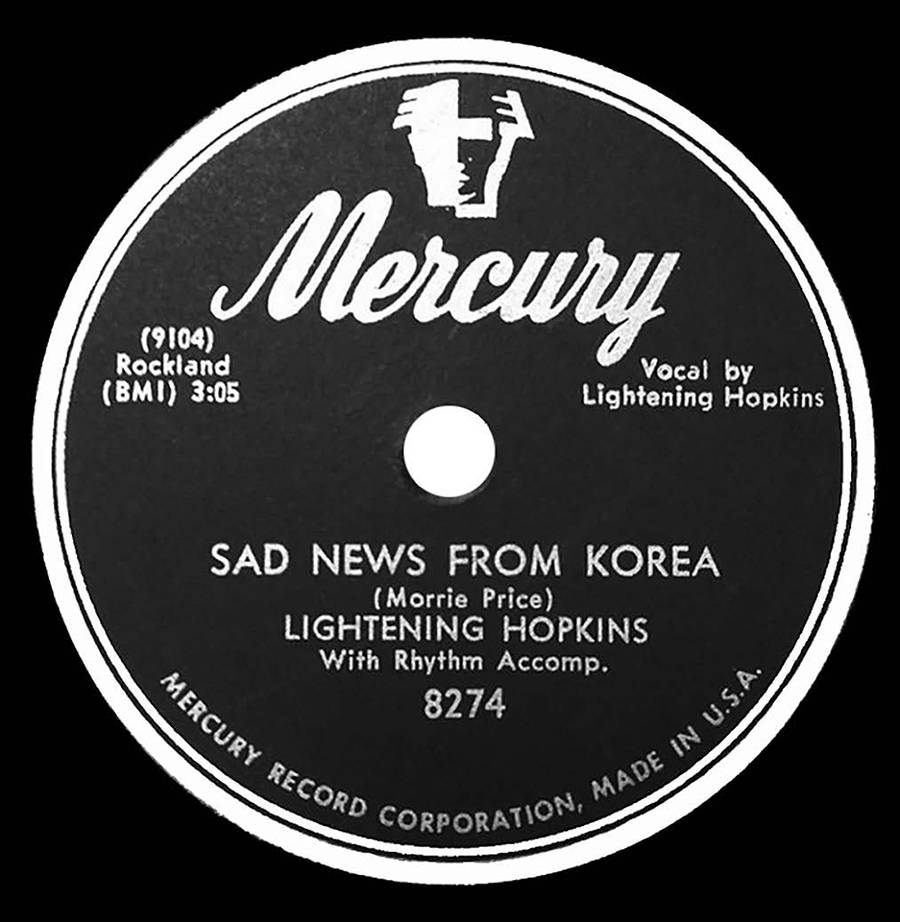

In 1951, Hopkins began working with producer Bobby Shad, who was based in New York City. In addition to his own Sittin’ In With label, Shad also had contacts with Mercury Records and Decca Records. Lightnin’ recorded sessions for Shad in both the Big Apple and the Bayou City. And per his usual practice, he demanded payment in cash per song, indifferent to the song’s ownership or any future royalties.29

Hopkins, on acoustic guitar, and Donald Cook on bass, cut “Sad News from Korea” (Mercury 8274) in Houston during the summer of 1951.30 Mercury Records issued the single as “Lightening [sic] Hopkins with Rhythm Accomp.” With composer credits going to Morrie Price, one of Bobby Shad’s pseudonyms.31 In “Sad News from Korea,” Hopkins evokes a parent’s dilemma when a son goes missing in action. Is he alive or is he dead? Here Lightnin’ captures the moment of a mother’s lamentation.

Well poor mother runnin’, cryin’, wonderin’ where my poor son could be.

[Spoken] Don’t worry, mama.

Whoa, poor mother runnin’, cryin’, Ooh, Lord, where could my poor child be.

Whoa, I just want you to answer my prayer, please sir,

God send my poor child back to me.

Even though President Truman had issued an executive order in 1948 instituting equality of treatment and opportunity for all persons in the armed services, when the Korean conflict began, US troops were still in effect segregated. But by 1951, with casualties on the rise and trained replacements in short supply, common sense and necessity forced large scale racial integration to take place.32

The fighting in Korea dragged on until an armistice signing on July 27, 1953; two days later Hopkins was in a Houston recording studio with Bobby Shad laying down eight tunes, including “The War Is Over” (Decca 28841) with writer credits to Bob Shad.33 Hopkins (back on electric guitar) and Cook are joined by Connie Kroll on drums serving up off the-cuff accompaniment just right for Lightnin’s celebration of a soldier returning home to his wife, while grousing and feigning the likelihood of physical violence.

Yeah, you know the war is over

Now I’ve got a chance to go back home

Whoa, you know, if that woman done spent all my money

I’m gonna whup her for doing me wrong

Yeah, you know that’s what mother been praying

For ’em to send her poor child back home

Yes, but you know it’s a sin and a shame for him to come back

Find every dime he made is gone.

That said, the singer is still confident that the transition to civilian life will be an easy one, and the couple can resume their relationship: “Now the war is over, baby, ain’t you glad/ You know you can get back and that old used to be/Have the same good times you used to have.”

Cold War tensions between the United States and the Soviet Union continued throughout the 1950s. The early months of John F. Kennedy’s administration in 1961 were especially fraught as a result of the botched Bay of Pigs invasion in April followed by the Berlin Crisis and the construction of the Berlin Wall in August.34 On August 16, 1961, Hopkins recorded two songs, “Got Me a Louisiana Woman” backed with “War Is Starting Again” (Ivory 91272), in the ACA Studio on Fannin Street for Ivory Lee Semien’s Ivory Records.35 “War Is Starting Again” finds Lightnin’ with a lot on his mind.

First, there is the emerging threat of war: “Whoa, you know this world is in a tangle, baby/I believe they gonna start war again.” Not to mention the collective anxiety it will bring: “Yeah, there gonna be mothers start to worry/Yes, there gonna be as many girls that lose a friend.” Hopkins also refers to President Kennedy’s decision to significantly increase the size of the military and step up draft calls in response to the Soviet actions in Germany: “Well, I got the news this morning/Right now they need a million men.”

Even though he had yet to travel outside the country himself, Lightnin’ tosses in this embellishment: “Whoa, you know I been overseas once/Oh, Lightnin’ don’t want to go there again/Lord have mercy!” And finally, he reminds the listener once more that the men left behind will be more than happy to look after the women: “Yeah, you know my girlfriend got a boyfriend in the Army that fool ’bout to go overseas/You know I don’t hate it so bad because, boy, you know there’s a better break for me.”

“War Is Starting Again” is deliberately paced, “unpolished but packed with atmosphere,” with Elmore Nixon’s piano vamping with Hopkins’s electric guitar.36 The bluesman’s impassioned singing further conveys the gravity of the message.37 Twenty years later, Jewell Records reissued the Ivory single as simply “War Is Started”/“Louisiana Woman” (Jewell 857) with both sides now assigned to S. Joseph.38 And in 1992 when “War Is Starting Again” turned-up on Hopkins’s Lonesome Life (Collectables COL CD-5262), Roy C. Ames, the producer of the album, retitled the song “The World’s in a Tangle.”39

Since the end of World War II, the United States had been providing economic and military aid in Indochina, first to the French and after 1954 to South Vietnam. As America’s direct military involvement continued to grow, by 1968 there were more than 500,000 troops posted to Vietnam.40 This would be the first armed conflict since the Revolutionary War in which American forces were wholly integrated from the onset. And because of a variety of factors ranging from voluntarism to bias, African Americans were more liable to serve in combat units.41 1968 was also the year Martin Luther King, Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy were assassinated and major riots occurred in cities across the United States. A growing opposition to the war and the draft within the Black community further heightened tensions among Black and white troops.42

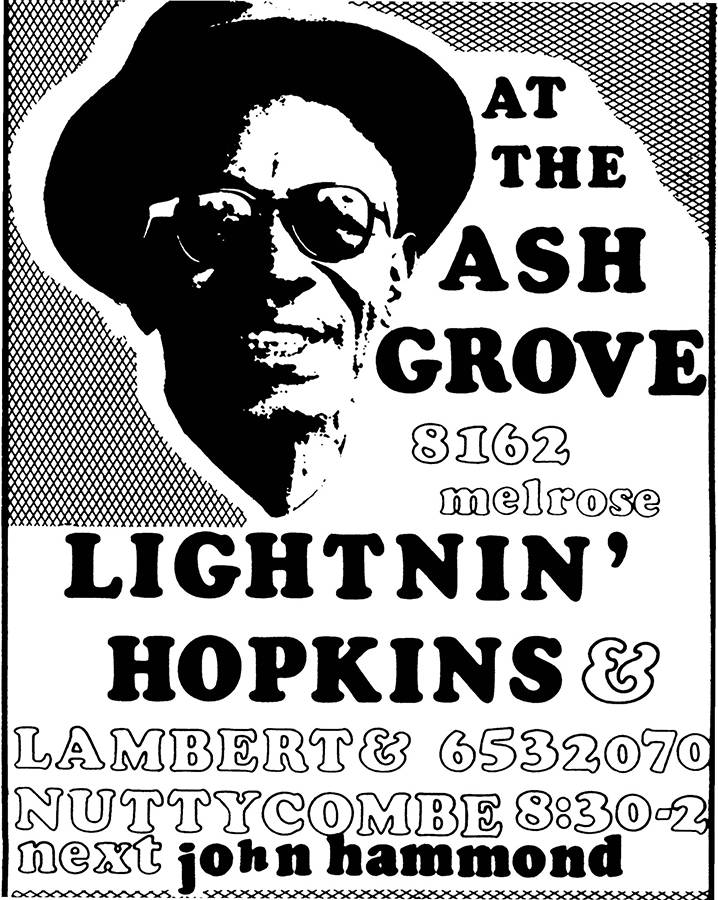

Hopkins was offering his own assessment of the situation in Southeast Asia as evidenced by a May 6, 1966, performance of the simply-titled “Vietnam” at the Ash Grove, Ed Pearl’s folk music club in Los Angeles. Pearl began booking Lightnin’ back in 1960 when the bluesman was making the transition to playing for white audiences as part of the folk-blues revival then sweeping the country, and the club owner appreciated the independent, uncompromising stance Hopkins took performing his music far beyond the environs of the Third Ward.43

Speaking to the Ash Grove audience, Lightnin’ interjects wryly humorous comments laced with a touch of sarcasm indicating his growing disenchantment with the draft and the war.

They say they gonna take one-eyed peoples and one-armed folk, yeah, and they want to know why. Well, they say that the one-armed person can lift the load . . . and the one-eyed person can lead ’em on . . . so you know it’s something to think about.44

And in the song that follows, he issues this sardonic challenge: “If you want to fight and be bad/Just take yourself to Vietnam/That’s where they’re raisin’ plenty of fights.”45

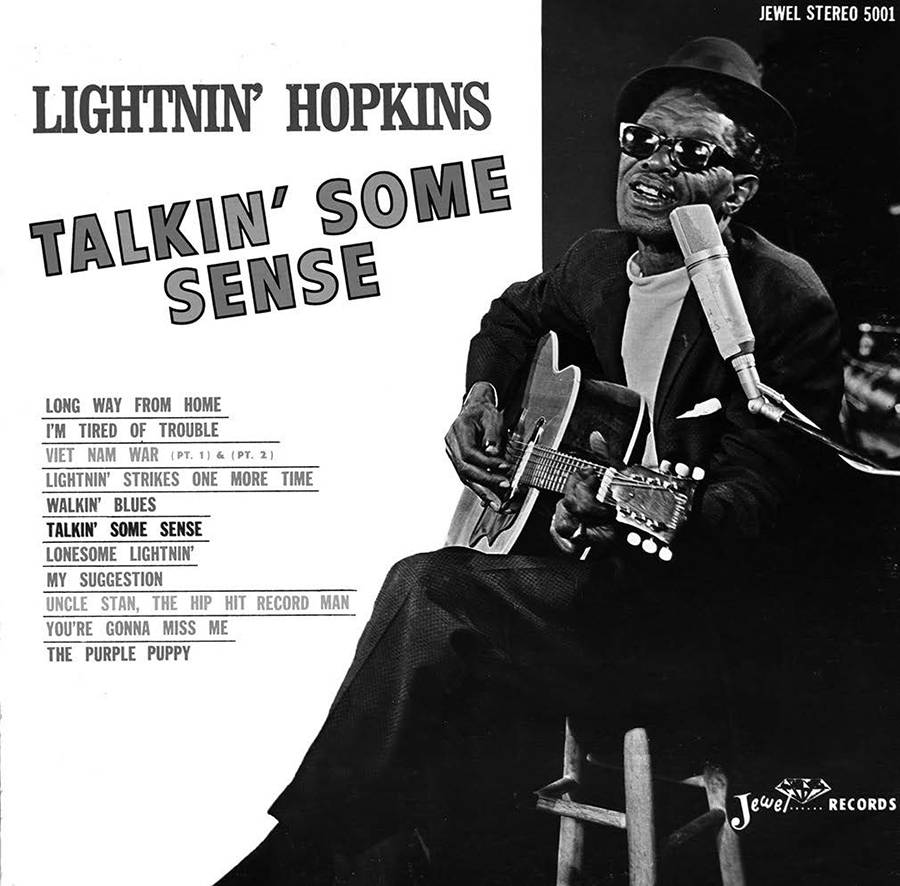

Hopkins recorded “Viet Nam War (Pt. 1) & (Pt. 2)” on January 17, 1968, in the ACA Studios for Stan Lewis’s Jewel Records (with Viet Nam spelled as two words). Lewis included the song on Hopkins’s 1968 album Talkin’ Some Sense (Jewel LP 5001).46 Elmore Nixon again occupies the piano bench along with George “Wild Child” Butler plus bass and drums.

In “Viet Nam War (Pt. 1) & (Pt. 2),” Lightnin’ mentions the President–“Mister Johnson is tellin’ everybody exactly what he want them to do”–but he is again primarily focused on a mother’s anguish with one son already in in the war zone and another possibly on the way. “Mama said, son, how can you be happy/When your brother way over in Viet Nam?/ . . . What if Uncle Sam was to call you, boy?/Oh, I would miss you so much I may die.”

A quick aside here: In 1993, the Oblivians waxed “Viet Nam War Blues” (Goner Records 2 Gone). And the Memphis, Tennessee, garage-punk band slash and smash their way through a cover version of Lightnin’s “Viet Nam War (Pt. 1) & (Pt. 2)” with proper attribution to the bluesman.

Hopkins recorded the song again on April 15, 1968, for Roy Ames, this time titled “Vietnam War.” And he joined Billy Bizor, another of his “purported cousin[s],” in the ACA Studios.47 Bizor’s moaning harmonica provides an additional dimension to the song’s gloomy message. This version, with Vietnam spelled as one word, ended up on Billy Bizor’s 1988 Blowing My Blues Away (Home Cooking HCS-111).48

Four days earlier in the same studio with Roy Ames producing, Hopkins turned to the past, reflecting on Talkin' Some Sense Album featuring "Vietnam War Parts 1 & 2." From the Author's Collection. War News Blues: Lightnin’ Hopkins, World War II, Korea, and Vietnam V15U the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in the slowly paced “December 7, 1941.”49 The first verse is a variation on a stanza taken from Peter “Doctor” Clayton’s 1942 “Pearl Harbor Blues” (Blue Bird B9003).50 “December the seventh, whoa, nineteen hundred and forty-one/Yeah, you know that’s when the Japanese flew over Pearl Harbor/Ohhh, men they were droppin’ bombs by the ton.” And Lightnin’s fixation on a mother’s response continues.

Poor mama she was sittin’ cryin’ wonderin’ did they bomb her poor child

Whoa, whoa, Lord, did they bomb my baby child

Yeah, you know that’s when they flew over Pearl Harbor

Boy, they dropped bombs ’til they got tired.

Ames chose “December 7, 1941” for inclusion on a 1969 various artist compilation, Soul . . . In the Beginning (Avco Embassy AV 33006), with additional selections by Johnny Winter, T-Bone Walker, Clifton Chenier, and Billy Bizor.51

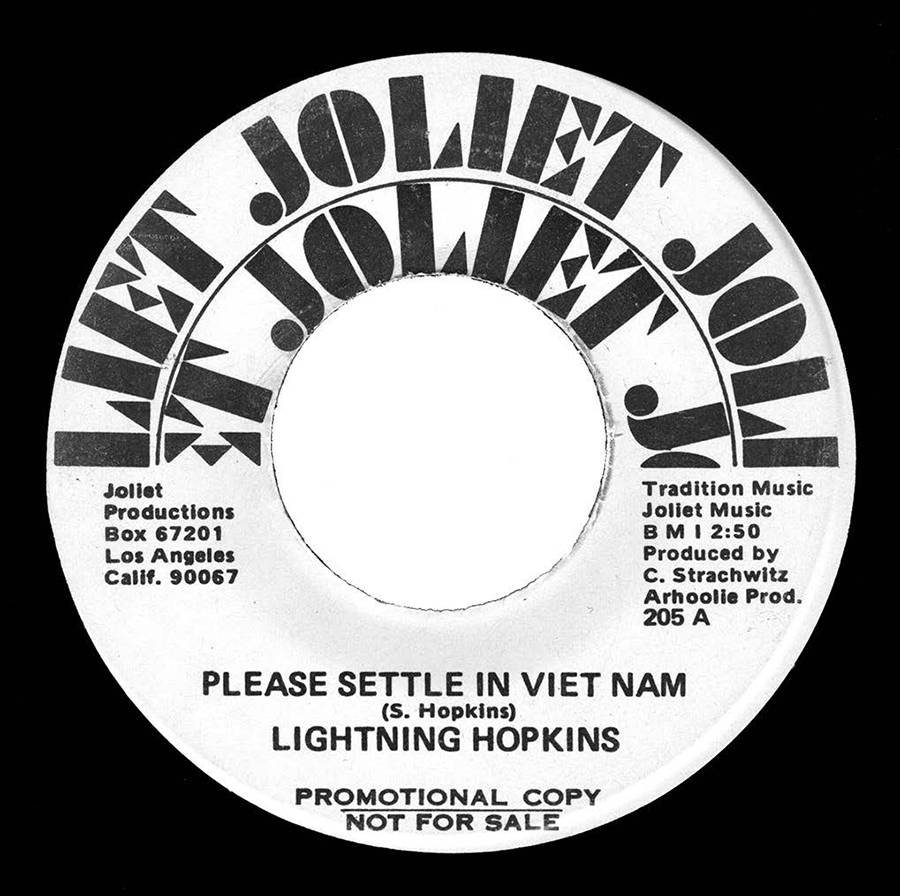

“Please Settle in Viet Nam” is Hopkins’s final and most complex statement on the quandary of Southeast Asia. He recorded the song for Chris Strachwitz in Berkeley on May 20, 1969. Strachwitz quickly released it, backed with “Once a Gambler,” on 45 rpm (Joliet 205) and then again in 1973 on Lightning Hopkins in Berkeley (Arhoolie 1063).52 By 1969, the anti-war movement was reaching a crescendo, and, as the song title makes clear, there was a growing realization that the only permanent solution was to “settle,” i.e. negotiate an end to the fighting in Vietnam.

“Please Settle in Viet Nam” is populated with familiar subjects: a mother’s concern and the ever-present backdoor man. “My mama was praying/She said please let thy kingdom come/She said please let it be an ending to the war/Please settle it in Viet Nam.” And then there is the incessantly cynical Jody. “My girlfriend got a boyfriend fighting/She don’t know when that man coming back home/I said I hope he’ll stay forever/‘Cause I ain’t gonna leave that little girl alone.”

But Hopkins also expresses sympathetic understanding for the circumstances of all the boyfriends. “You know it’s a shame for the people to do this way/Taking the young people out of the United States/Taking them over to Viet Nam and they’ve got to stay.” The last verse serves up an interesting mix.

You know Uncle Sam dug trenches,

Yeah, he dug ’em way over in no man’s land.

Uncle Sam he wadn’t no woman, little girl,

Tell me did he take your man?

The mention of trench warfare is an indication of Hopkins’ limited understanding of what was actually taking place on the ground. Traditional trenches like those of World War I were not really employed in Vietnam. But when they were, it was the Communist forces that were more likely to do so.53 The verse’s last two lines could well be a reference to Oran “Hot Lips” Page’s “Uncle Sam Blues.”54 Originally released in 1944 on V-Disc, Page makes no bones about the government’s authority to conscript and its emotional toll. “Uncle Sam ain’t no woman/But he sure can take your man/Women ringing hands and a-cryin’/All over the land.”55

With the war still raging, Hopkins went into the studios of KCET-TV in Los Angeles on October 21, 1970, to tape a concert performance for broadcast the next year on the PBS series Bobquivari.56 One of the songs on the program is titled “Questionnaire Blues.” In this case, questionnaire is a reference to the letter a man receives from the local draft board with orders to report for a physical examination and induction.57 Blues great B.B. King recorded a similar “Questionnaire Blues” in 1951: “I got my questionnaire/And they need me in the war.”58 In “Korea Blues,” also from 1951, J.B. Lenoir intones, “Lord, I got my questionnaire/Uncle Sam gonna send me away from here.”59

Before singing, Lightnin’ pauses to share thoughts on his own experience upon receiving his draft notice, an order from which he was spared after the knifing incident.

I look in my mailbox, and I found my questionnaire. You know that was pretty tough, you know, at my age. Uncle Sam want me in the Army. I don’t want to go because I have too many fights over here. But I’ll take it easy and go ahead and go over there because it might [be] easier over there than it is for me here [chuckles]. Have mercy. So I’m gonna play this song. It’s gonna be low, slow, and easy. I want-cha to pay attention.60

“Questionnaire Blues” is perhaps the only time Hopkins sings in the first person from the inductee’s perspective and not from Jody’s point of view.

Looked in my mailbox this morning

Do you know I found my questionnaire.

Yes, I looked in my mailbox this morning

Po’ Lightnin’ found his questionnaire.

You know Uncle Sam say, “Lightnin’, you aint’ got no business here.”

And I told him, “What if I should go [in] the Army Who gonna take care of my wife and child?”

[spoken] Had a partner standing beside me said,

“Me, brother.”

Well, if I should go to the Army

Who gonna take care of my little wife and child?

Yeah, you know if I should die on the battlefield

Nobody know that day if I die.

Author, journalist, and musician Robert Palmer has described Hopkins as “a chronicler of his life and his community who’s the closest thing to the tradition-bearing ‘griots’ of West Africa.”61 And certainly in the case of Hopkins’s war-related songs, community reaches beyond the African- American population with the singer addressing topics that touch us all: the universal themes of separation from family, a mother’s love, temptation back on the home front, the ubiquitous Jody, and the simple reality that in war, death is indeed a fact of life.

The continual presence of a mother in these songs is a vivid reminder, too, of Hopkins’s affection for his own mother, Frances. Alan Govenar interviewed several longtime Centerville residents who affirmed Sam’s devotion to Frances, regularly visiting her and offering financial assistance.62 And during the televised KCET performance, Lightnin’ imparts advice and personal testimony to the predominately collegeage audience. “You should go home sometime . . . you should never forget about your ol’ parents. . . . I never forgot to go back home to my mama.”63

As noted above, Hopkins’s “war-zone” dispatches are remarkably consistent, then. Interestingly enough, he refrains from specifically referring to matters of race. There is no mention of the rigid segregation within the US military that existed right up to the Korean conflict and the institutional bias that continued to linger. Furthermore, the Vietnam songs are devoid of commentary on the simmering tensions between Black and white troops as stateside societal issues spilled over into the military ranks in Southeast Asia.

It would be a mistake, however, to believe that Hopkins was soft-peddling his message because of an ever-growing white audience. With regards to race, such issues are implicit in the bluesman’s storytelling. Or as Tony Russell succinctly puts it, “What was in his head was largely unaffected by where he hung his hat.”64 And it is clear that Hopkins still has his finger on the pulse of the people. He waxed “Viet Nam War (Pt. 1) & (Pt. 2)” in 1968 and “Please Settle in Viet Nam” in 1969, the years when it was becoming apparent to the world that any chance of the United States actually winning the war was fast slipping away.

Notes

- Portions of this paper were presented at the annual meeting of the Texas State Historical Association in Austin on February 29, 2020. For input and suggestions along the way, a tip of the hat to David Coffey, Scott Downing, Melody Kelly, Bill McClung, Jack Pierce, Mike Pierce, Gary Shanafelt, Tyler Stoddard Smith, and Mary Helen Specht.

- Mack McCormick, “Lightnin’ Hopkins: Blues,” in Jazz Panorama: From the Pages of The Jazz Journal, ed. Martin Williams (New York: Collier Books, 1964), 313.

- Tony Russell, “Essential Blues,” MOJO, April 2003, 122.

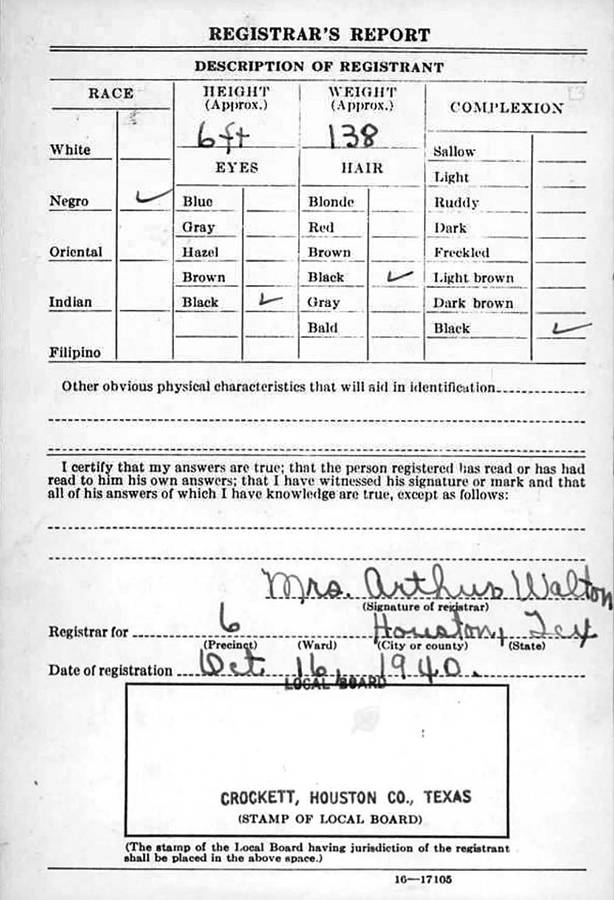

- Alan Govenar has found evidence that Hopkins might have been born in 1911, not 1912; see Alan Govenar, Lightnin’ Hopkins: His Life and Blues (Chicago: Chicago Review Press, 2010), 2. And based on his scrutiny of the 1920 census records and the Social Security Death Index, researcher Bob Eagle concurs; see Bob Eagle and Eric S. LeBlanc, Blues: A Regional Experience (Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger, 2013), 294. It should be noted, however, that when Hopkins registered for the draft in 1940, his birth year is given as 1912, not 1911. Note date in the pictured draft card.

- It has long been believed that Hopkins and Alexander were related. Timothy O’Brien, another Hopkins biographer, identifies Alexander as “Hopkins’ first cousin on his mother’s side;” see Timothy J. O’Brien and David Ensminger, Mojo Hand: The Life and Music of Lightnin’ Hopkins (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2013), 19. Alan Govenar, on the other hand, maintains, “Sam claimed that Alexander was his cousin, but no direct kinship has ever been established. Sam had a very loose definition of the term ‘cousin’ that he tended to use more as an expression of endearment than a statement of fact;” see Govenar, Lightnin’ Hopkins, 22. In addition to Alexander, the “cousins” list, real or otherwise, includes Billy Bizor, Albert Collins, and Clyde Langford; see Joe W. Specht, “Kissing Cousins: The Bluesmen of Leon County,” paper presented at 2019 Fall Symposium of the Central Texas Historical Association in New Braunfels on November 16, 2019.

- Lightnin’ Hopkins, “I First Come into Houston,” My Life in the Blues (Prestige PR 7370, 1965).

- In his December 2, 1964, interview with Samuel Charters, Hopkins describes his initial recording session and how the record company assigned the “Thunder” and “Lightnin’” nicknames; see Lightnin’ Hopkins, “I Do My First Record and Get My Name,” My Life in the Blues.

- Andrew Brown and Alan Balfour, “Discography” in Govenar, Lightnin’ Hopkins, 241. I have chosen to use Brown and Balfour’s revised, updated Hopkins discography for his recording session information in lieu of Les Fancourt and Bob McGrath, The Blues Discography, 1943-1970, 3rd ed. (West Vancouver, BC: Eyeball Productions, 2019).

- Alan Govenar theorizes that sales of Hopkins’s early Aladdin records “didn’t do very well,” yet, he also identifies “Katie Mae Blues” as “[a] hit” for Hopkins; see Govenar, Lightnin’ Hopkins 44, 116.

- Andy Bradley and Roger Wood, House of Hits: The Story of Houston’s Gold Star/SugarHill Recording Studios (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2010), 8.

- Govenar, Lightnin’ Hopkins, 48; Bradley and Wood, House of Hits, 23.

- Bradley and Wood, House of Hits, 25.

- Discographers have long taken for granted that Hopkins first recorded “Short Haired Woman” for Aladdin Records, but Andrew Brown makes a strong case for Gold Star 3131 being the original; see Govenar, Lightnin’ Hopkins, 293. For more on the subject, see Joe W. Specht, “Gimme Back That Wig: The Coiffure Stylings of Lightnin’ Hopkins,” East Texas Historical Journal (forthcoming).

- Govenar, Lightnin’ Hopkins, 46-47; Bradley and Wood, House of Hits, 25.

- Brown and Balfour, “Discography,” 246.

- Bernard C. Nalty, Strength for the Fight: A History of Black Americans in the Military (New York: Free Press, 1986); Gerald Astor, The Right to Fight: A History of African Americans in the Military (Novato, CA: Presidio Press, 1998); and Gail Buckley, American Patriots: The Story of Blacks in the Military from the Revolution to Desert Storm (New York: Random House, 2001) provide thorough overviews of African American participation in the armed services from the American Revolution to Vietnam.

- George Q. Flynn, “Selective Service and American Blacks During World War II,” Journal of Negro History 69, no. 1 (Winter 1984): 14.

- U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, Selective Service Registration Cards, World War II: Multiple Registrations (NARA Fold3 Publication, 2012); WWII Draft Registration Cards, www.fold3.com/title/816/wwii-draft-registration-cards.

- Paul Oliver and Mack McCormick, The Blues Come to Texas: Paul Oliver and Mack McCormick’s Unfinished Book, Compiled by Alan Govenar with Documentation and Essays by Alan Govenar and Kip Lornell (College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 2019), 173.

- Govenar, Lightnin’ Hopkins, 37.

- Tyina Steptoe, “‘Jody’s Got your Girl and Gone’: Gender, Folklore, and the Black Working Class,” Journal of African American History 99, no. 3 (Summer 2014): 251.

- Ibid., 262. As Steptoe points out, “Jody reached his height of popularity during the Vietnam War. . . . Soldiers marched to Jody calls overseas, while civilians in the United States danced to songs like . . . Johnnie Taylor’s ‘Standing in for Jody’ and ‘Jody’s Got Your Girl and Gone.’” (264)

- Fancourt and McGrath, The Blues Discography, 1943-1970, 633.

- Flynn, “Selective Service and American Blacks During World War II,” 14-16; Nalty, Strength for the Fight, 181-184. Exclusion from the Air Corps changed, of course, with the formation of the Tuskegee Airmen, and Black Marines became a reality, too, with African Americans eventually seeing action on Peleliu.

- Brown and Balfour, “Discography,” 248.

- Clay Blair, The Forgotten War: America in Korea, 1950-1953 (New York: Times Books, 1987), 522-523.

- Fancourt and McGrath, The Blues Discography, 1943-1970, 140; Bob Groom, “Beyond the Mushroom Cloud: A Decade of Disillusion in Black Blues and Gospel Song,” in Ramblin’ on My Mind: New Perspectives on the Blues, ed. David Evans (Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2008), 338; Guido van Rijn, The Truman and Eisenhower Blues: African-American Blues and Gospel Songs, 1945-1960 (New York: Continuum, 2004), 74-75.

- Brown and Balfour, “Discography,” 248.

- Govenar, Lightnin’ Hopkins, 58-60.

- Brown and Balfour, “Discography,” 250.

- Ibid.; Govenar, Lightnin’ Hopkins, 59.

- Richard M. Dalfiume, Desegregation of the U.S. Armed Forces: Fighting on Two Fronts, 1939-1953 (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1969), 218-219; Nalty, Strength for the Fight, 259; Astor, The Right to Fight, 375-376; Buckley, American Patriots, 362-363. With the Truman executive order, an integrated military became more of a reality during the Korean conflict, and it is worth noting how African-American participation in combat is positively portrayed by Hollywood in movies made during the period; see Gerald Early, “Integrating the Military” in A New Literary History of America, eds. Greil Marcus and Werner Sollors (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2009), 786-790.

- Brown and Balfour, “Discography,” 250; van Rijn, The Truman and Eisenhower Blues, 94.

- John Lewis Gaddis, The Cold War: A New History (New York: Penguin Press, 2005), 74.

- Brown and Balfour, “Discography,” 262; Guido van Rijn, Kennedy’s Blues: African-American Blues and Gospel Songs on JFK (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2007), 30.

- Tony Russell, “Lightnin’ Hopkins,” in The Penguin Guide to Blues Records, eds. Tony Russell and Chris Smith (New York: Penguin Books, 2006), 280.

- “War Is Starting Again” and “Got Me a Louisiana Woman” are also included on Lightnin’ Hopkins, Lightnin’ Strikes (Vee Jay LP 1044, ca. 1962).

- Fancourt and McGrath, The Blues Discography, 1943-1970, 279.

- In the notes to the Collectables compact disc, Ames identifies “The World’s In a Tangle” as “previously unissued;” see Roy C. Ames, “Notes,” Lightnin’ Hopkins, Lonesome Life (Collectables COL CD-5262, 1992). But it is just as likely it is the same take as “War Is Starting Again” without the fade-out at the end; see Brown and Balfour, “Discography,” 262.

- Gene Allen Smith, David Coffey, and Kyle Longley, In Harm’s Way: A History of the American Military Experience (New York: Oxford University Press, 2020), 449-452.

- James E. Westheider, Fighting on Two Fronts: African Americans and the Vietnam War (New York: New York University Press, 1997), 2, 8, 14-17; Nalty, Strength for the Fight, 289.

- Nalty, Strength for the Fight, 301-311; Astor, The Right to Fight, 436-437; Buckley, American Patriots, 415-416, 424-425; Smith, Coffey, Longley, In Harm’s Way, 464-465.

- Govenar, Lightnin’ Hopkins, 96, 100.

- “Lightnin’ Hopkins at Ash Grove, May 6, 1966 (Set 1),” Wolfgang’s Authentic Music & Merchandise, www.wolfgangs.com/music/lightninhopkins/ audio (accessed October 16, 2018).

- Ibid.

- Brown and Balfour, “Discography,” 277-278.

- Govenar, Lightnin’ Hopkins, 27.

- Brown and Balfour, “Discography,” 279.

- Ibid., 279.

- Robert M. W. Dixon, John Godrich, and Howard Rye, Blues & Gospel Records, 1890-1943, 4th ed. (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997), 164; Guido van Rijn, Roosevelt’s Blues: African-American Blues and Gospel Songs on FDR (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1997), 151-152.

- Brown and Balfour, “Discography,” 279. The April 11, 1969, session in its entirety with “December 7, 1941” is included on Lightnin’ Hopkins, Shootin’ Fire (Cicadelic Records CICD-41169, 2015).

- Ibid., 282. For all of Hopkins’s releases on Arhoolie Records, Stratchwitz spelled Lightnin’ with a “g” as Lightning.

- Spencer C. Tucker, ed., Encyclopedia of the Vietnam War: A Political, Social, and Military History, 2nd ed. (Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2011), 447-448, 579-583.

- Bill McClung, email to the author, September 21, 2019.

- Todd Bryant Weeks, Luck’s In My Corner: The Life and Music of Hot Lips Page (New York: Routledge, 2008), 167.

- O’Brien, Mojo Hand, 214. The KCET-TV concert is included on Lightnin’ Hopkins Rare Performances (Vestapol 13022) DVD (2001).

- Hugo Keesing with Bill Geerhart, Battleground Korea: Songs and Sounds of America’s Forgotten War (Holste, DE: Bear Family Productions, 2018), 32.

- Fancourt and McGrath, The Blues Discography, 1943-1970, 352.

- Ibid., 379.

- Lightnin’ Hopkins Rare Performances.

- Robert Palmer, “Lightnin’ Hopkins at 68: Still Singing Those Blues,” New York Times, October 31, 1981; reprinted in Robert Palmer, Blues & Chaos: The Music Writing of Robert Palmer, ed. Anthony DeCurtis (New York: Scribner, 2009), 52.

- Govenar, Lightnin’ Hopkins, 125-136. The testimonies of the neighbors stand in sharp contrast to Mack McCormick’s liner notes for the Smokes Like Lightning album; here McCormick asserts that Sam long ignored Frances and left it up to older brother Joel “to try and support their aging mother on his earnings as a yardman;” see Mack McCormick, “Notes,” Lightnin’ Hopkins, Smokes Like Lightning (Prestige Bluesville BV-1077, 1963); see also Oliver and McCormick, The Blues Come to Texas, 375.

- Lightnin’ Hopkins Rare Performances.

- Russell, “Lightnin’ Hopkins,” 279.

Images

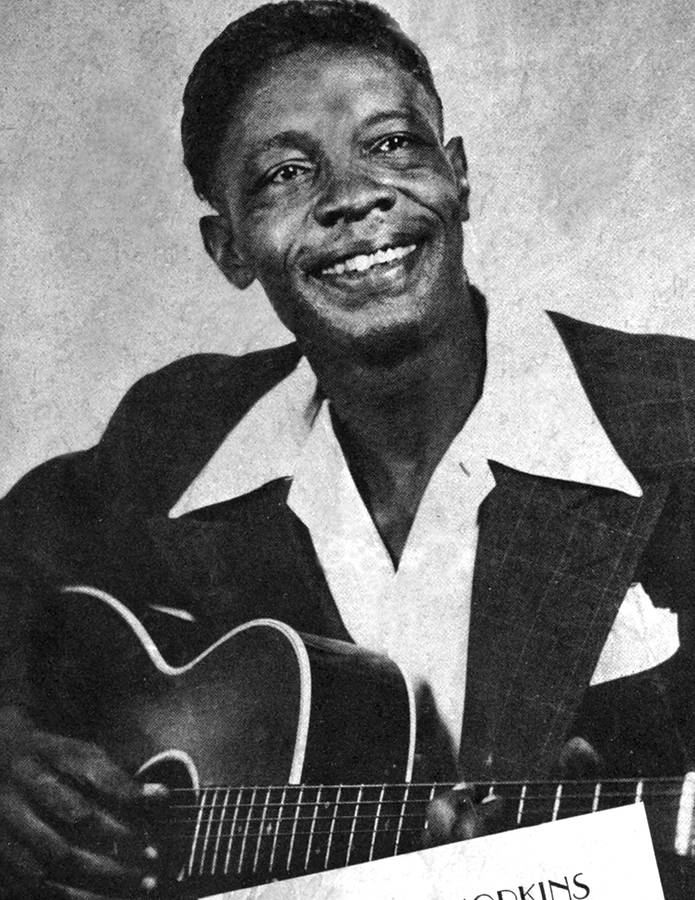

- Publicity photo circa 1949. Courtesy of Smithsonian Folkways Recordings and Arhoolie Records. From the author’s collection.

- "European Blues." Gold Star Records. From the Collection of Bill McClung.

- Lightnin’ Hopkins’ Draft Registration. U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, Selective Service Registration Cards, World War II: Multiple Registrations (NARA Fold3 Publication, 2012); WWII Draft Registration Cards.

- Lightnin’ Hopkins’ Draft Registration. U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, Selective Service Registration Cards, World War II: Multiple Registrations (NARA Fold3 Publication, 2012); WWII Draft Registration Cards.

- "Sad News from Korea," Mercury Records. From the Author's Collection.

- "The War Is Over," Decca Records. From the Author's Collection.

- Talkin' Some Sense Album featuring "Vietnam War Parts 1 & 2." From the Author's Collection.

- "Please Settle in Viet Nam." Joliet Records. From the Author's Collection.

- Lightnin' Hopkins at the Ash Grove Poster. From the Author's Collection