An Accidental Journalist: The Improbable Rise of Jan Reid

Diana Finlay Hendricks

Many books are described as “defining a generation,” but rarely does a magazine article grow into a book that withstands nearly fifty years and four editions. Jan Reid’s book defines more than a generation. It chronicles a new sound.

Singer-songwriter Robert Earl Keen calls Reid’s The Improbable Rise of Redneck Rock “the playbook for my generation.”1 Todd Snider says, “In 1986, as I was discovering Jerry Jeff and Willie and Billy Joe on stage, I was handed Jan Reid’s book. It was required reading. It’s the bible of the Austin Music Scene. In The Beginning.”2 Lyle Lovett, Jack Ingram, Charlie Robison, and others who have taken this burgeoning sound to national stages were influenced by the pioneers of this cosmic/ outlaw/redneck/progressive sound: the musicians, the club owners, the writers, photographers, and audiences who were spotlighted in Reid’s enduring The Improbable Rise of Redneck Rock.

Redneck Rock “the playbook for my generation.”1 Todd Snider says, “In 1986, as I was discovering Jerry Jeff and Willie and Billy Joe on stage, I was handed Jan Reid’s book. It was required reading. It’s the bible of the Austin Music Scene. In The Beginning.”2 Lyle Lovett, Jack Ingram, Charlie Robison, and others who have taken this burgeoning sound to national stages were influenced by the pioneers of this cosmic/ outlaw/redneck/progressive sound: the musicians, the club owners, the writers, photographers, and audiences who were spotlighted in Reid’s enduring The Improbable Rise of Redneck Rock.

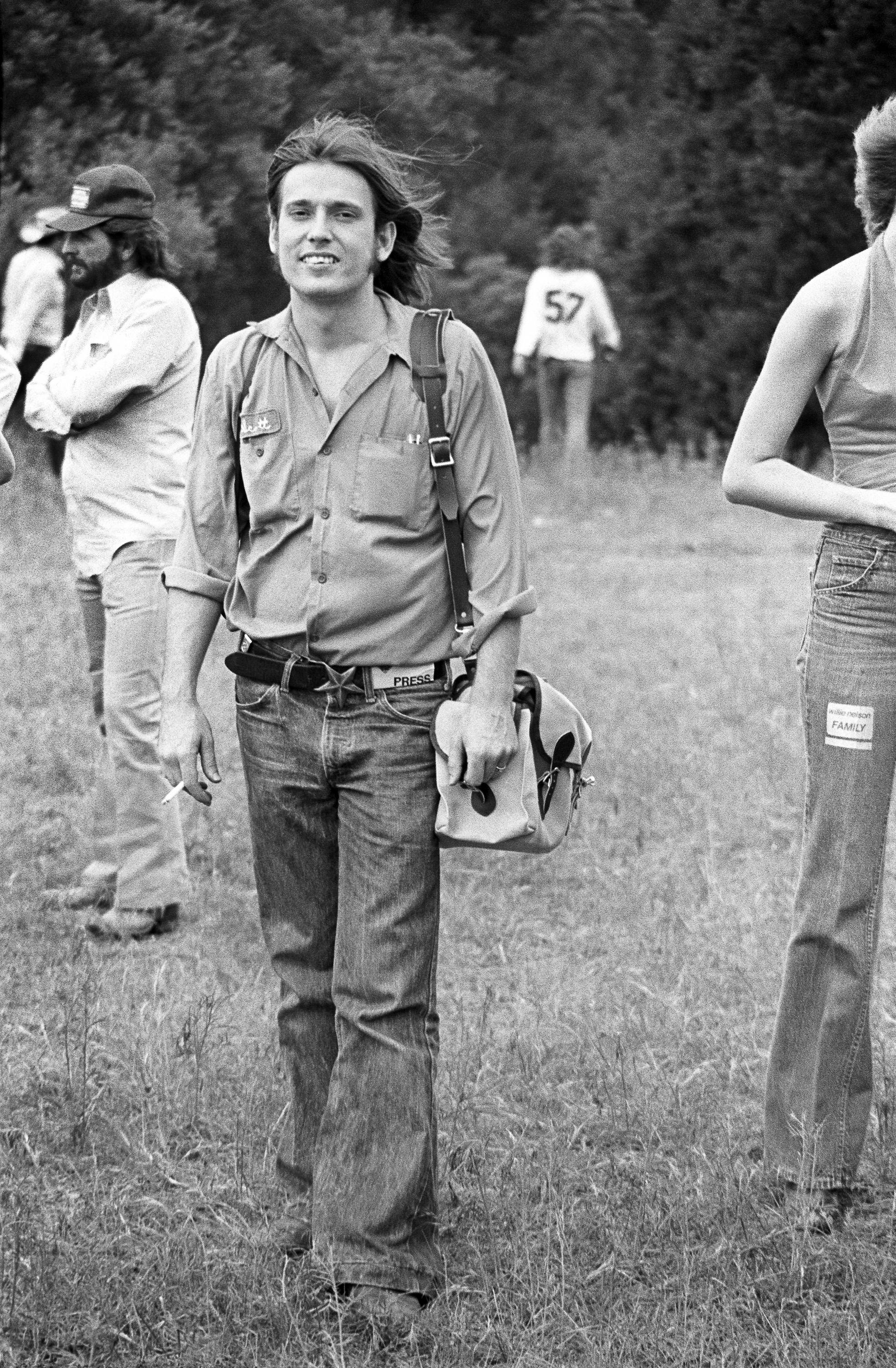

Jan Reid never intended to be a music writer. As his friend and fellow writer, W. K. “Kip” Stratton writes in the foreword to the latest edition (TCU, 2021), “He was in the right place (Austin, Texas) at the right time (the early 1970s) to witness firsthand a club scene . . . that came to define what we now call Americana music.”3

The 1970s brought new voices to music and literature in Austin. This renaissance helped to create music venues, publishing houses, and periodicals. In 1972, Texas Monthly was founded by a 26-year-old Dallas native Michael R. Levy, who hired William Broyles as the founding editor and Gregory Curtis as the first staff writer. Levy’s intention was to create a “writer’s magazine,” which led to the magazine fostering young, promising writers in the early days of their careers. After eight years at the helm of Texas Monthly, Broyles shifted gears into a successful screenwriting career, and Curtis went on to serve the longest term as editor of the iconic magazine, from 1981 to 2000.4

Jan Reid was among the first of those developing Texas Monthly writers. In November of 1973, he and Don Roth wrote a feature for the magazine entitled “The Coming of Redneck Hip: Rock and country music met in Austin. That friendship may make the state.”

The 5300-word feature spotlighted the Armadillo World Headquarters and the Vulcan Gas Company, Kenneth Threadgill and Eddie Wilson, Steve Fromholz and Michael Murphey, Doug Sahm and Jerry Jeff Walker. But, according to the article, one person stood head and shoulders above the rest.

If anyone is qualified to serve as high priest of Austin’s movement toward the big time, it’s the grinning, gentle rebel who made the music industry come to him on his own terms yet somehow remained the almost universally admired nice guy and artist. Willie Nelson has thus become a symbolic figure, the one man whose approach to life and music makes sense of Austin’s curious mix of freaks and rednecks, trepidation and ambition, naiveté and striving professionalism. And where symbolic heroes move, cults often follow.5

Prophetic words. Willie had left Nashville and come home to Texas in the summer of 1972, forging a trail for troubadours, singer-songwriters, and musicians who wanted to be artists instead of products. Today, fifty years later, Willie is clearly the most famous musician to come from that moment in Austin music.

But Willie was not the only artist Reid recognized as a future legend. Beyond that Texas Monthly article, Reid knew he had much more to say. A year and a half after the article, the first edition of The Improbable Rise of Redneck Rock was published by David and Joyce Lindsey’s Heidelberg Press. Lindsey said, “My wife, Joyce, and I had started a little publishing company that evolved into Heidelberg Press. We’d had some success with several other books, and I knew I wanted to do a music book. We knew Melinda Wickman (Swearingen). And she knew Jan. He wanted to do a book. And I don’t remember if I went to him or he came to me, but we both knew that something new was happening in Austin and it was very exciting.”

Jan was working as a sports editor for the New Braunfels Herald-Zeitung. In the early days of the book’s development, email and cell phones were nonexistent, and long-distance calls were expensive. Lindsey said, “Jan would write to me on foolscap paper — you know, the newsroom paper that yellows on Wednesday if you write on it on Monday. He would mail these ideas and I’d help with the structure, and we kept noodling with it until it fell into place.”

It didn’t take long for Reid to write the book. Less than two years after the Texas Monthly article appeared, in 1974, the book was in print.

“It was hard to promote anything in those days,” recalled Lindsey. “Joyce and I went to a lot of concerts and handed out flyers promoting the book. We went to Willie’s College Station Picnic. There was a tunnel that ran under the highway between the parking field and the concert stage field. We stood in that tunnel and handed out thousands of flyers to everyone coming through the tunnel moving toward the stage. After the music started, we walked out of the tunnel to listen to the music and found every flyer we had handed out – on the ground. It was disheartening.” Despite what they considered failed promotions, the book was a financial success for Reid and for Heidelberg Press.

Lindsey mentioned that as he was getting ready for this interview, he went through his files and found a printed postscript that never made it into the book. “Jan was a beautiful writer, and the fact that I found him and was able to work with him was pure dumb luck. Even this postscript that I found the other day was beautifully written. Jan was—what you saw was what you got. He was one of the most genuine people I have ever known.”

Lindsey recalled the origins of the title. “Our publishing office was in a garage apartment in our backyard. We had business meetings in the driveway. Jan and I bounced around with titles for a few days. Then he drove over afternoon and said, ‘I think I have it. The something-something-something . . . of . . . Redneck Rock.’”

Lindsey added, “Redneck is a word that is still around. Recently, I had to go to a funeral in Odessa [Texas] and stopped west of San Angelo for gas. The guy paying in front of me had ‘I’m a Redneck and Proud of it’ tattooed on his neck. West Texas never changes. I have always felt like it was the right word for the book.”6

Who knew that title—and what Jan wrote about music and hippies and bars – along with what he didn’t write—would stir up trouble?

The Controversies

[Jan Reid] comes in here talking about how I run a beer joint…quoted a junkie about how I’m trying to operate to keep alive. And it’s in hardback so it’s history; there ain’t nothing we can do about it. . . . You go to the library in ten years. And if you’re in the eighth grade and you’re writing a paper on the Austin music scene, and you pull that book out . . . it's history.

Eddie Wilson, Owner, Armadillo World Headquarters

In conversation with Michael Martin Murphey regarding

Jan Reid’s The Improbable Rise of Redneck Rock7

Photo by Scott Newton

When The Improbable Rise of Redneck Rock was published in 1974, it was not without controversy. The first, and likely most memorable, was when Michael (not yet using his middle name) Murphey objected. “He was mad about a lot of things. He didn’t think I had the credentials to write a book about him or any other musician,” Reid recalled, “and he didn’t want anything to do with rednecks. He was on the verge of separating himself from the cosmic cowboy scene and moving toward, I guess, a more sophisticated audience.”8

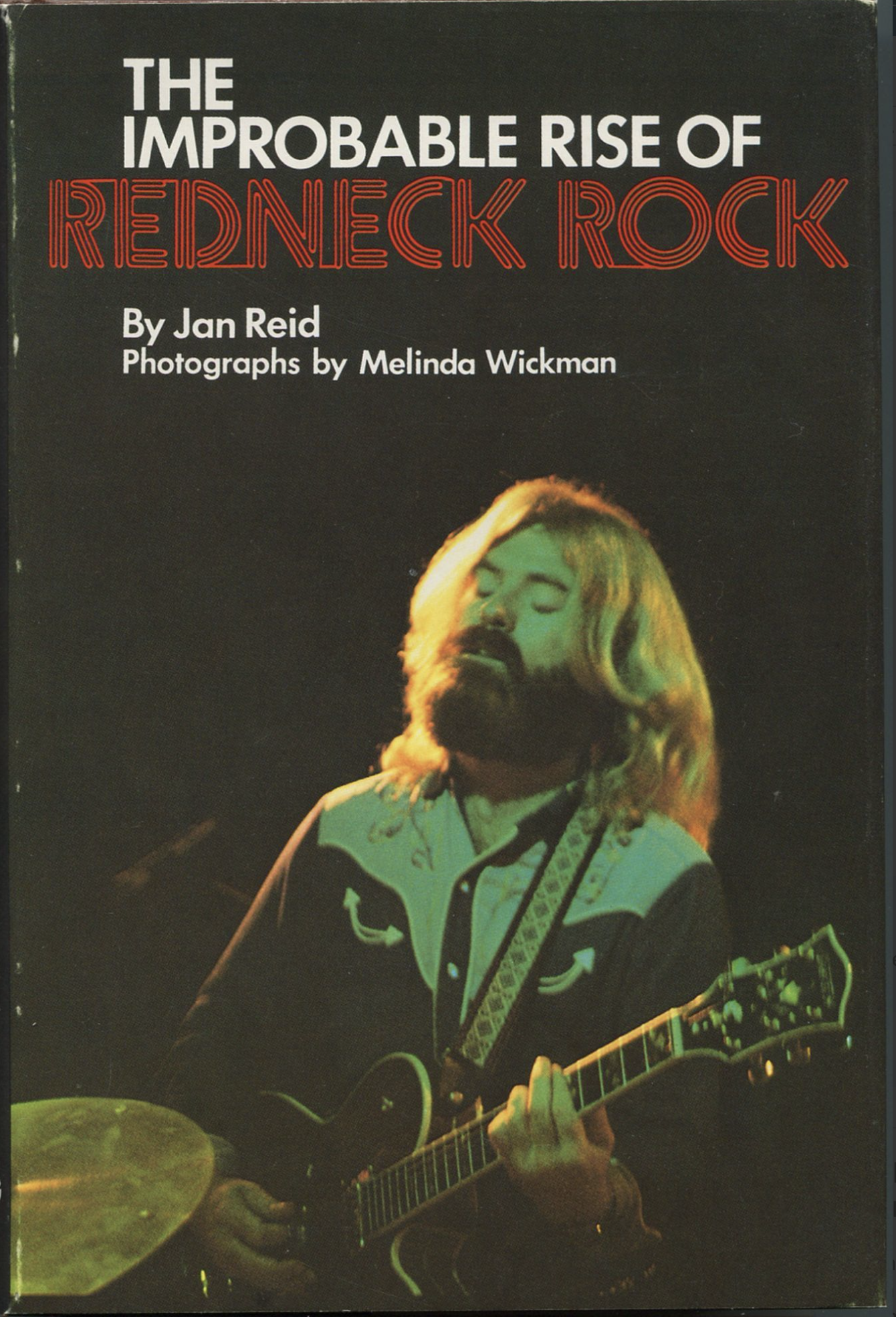

Michael Murphey threatened to sue for his picture being on the cover, because he didn’t like being described as “redneck.” Reid laughed as he recalled how that happened. “Willie [Nelson] was slated for the original cover, but the day Melinda [Wickman-Swearingen] went to shoot the cover, Willie had just shaved his beard and cut his hair and looked just like Elmer Fudd. We didn’t have time to wait for his hair to grow back so we went with a photo of Michael that Melinda had taken at a show.”9

A year after the book was published, Reid wrote in the Texas Folklore Society’s publication, “I anticipated some adverse reaction to the title, but not too much. Redneck was a pejorative born of class ethics, not ethnicity. . . . A harsher term of similar meaning was ‘poor white trash.’ I quickly found, however, that many young people were extremely sensitive to the term. When the book was published, [Murphey] demanded either a new title or else another likeness on the dust jacket.”10

Reid said that the lowest point came when he was a guest on a radio program in San Antonio. The drift of a young caller’s argument was that rock music was sacrosanct and ought to remain separate from rednecks and their terrible country music. Obviously disgusted, he asked, “And don’t you think that title’s kind of—offensive?”

Reid said, “I weakly replied that I could only speak for myself.”

“Well, I think you’re an idiot,” the caller said, and hung up.11

Eddie Wilson, whom Reid refers to in a later edition of the book as “the most important and enduring businessman and champion Austin music ever had,” disputed the way Reid described him and his business in the first edition of the book. But Wilson wrote in his 2018 memoir, “All in all, he treated me fairly. . . . I did get treated pretty well in the book.”12

For a while, rumors swirled about Murphey filing a lawsuit to have The Improbable Rise of Redneck Rock cease publication and be removed from bookstores, citing the publisher’s lack of permission to use his image on the cover. The lawsuit never materialized but the undercurrent managed to fuel even more interest in the book.

Bobby Earl Smith, attorney and pioneer of the Austin music scene, was one of the founders of Freda and the Firedogs, a popular dancehall band during that era. “It’s easy to see looking back,” Smith said. “Whatever you were immersed in appeared to be the entire world of Austin music. There were wheels within wheels in the music scene, but in the middle of it, you only see what you see. And Jan was focused on what I would call the folk contingent. Those folk singers, and a few rock musicians, saw what was happening in Austin, so they put together a band with a steel guitar and a fiddle, and bought a cowboy hat. My blues friends called it the progressive country scare.”

A lot of us were mad about the book because of what he didn’t write about. I was a pissant. I was complaining to anyone who would listen about Jan getting it all wrong. He didn’t feature Alvin Crow and the Pleasant Valley Boys. He didn’t write about Freda and the Firedogs. We were not in the book. I got really mad, and real fast. We (Freda and the Firedogs) were making a mark. We signed a contract with Jerry Wexler at Atlantic Records, who was in Austin trying to capture this new sound. He wanted Freda and the Firedogs. Our great sin of omission was that we kept Wexler waiting at the altar too long. It was only about seven or eight weeks, but during that interim he fell out of favor with the label and his Austin experiment fell apart. Our contract was lost in the shuffle. Still, we should have been more than a one-line mention in that first book. I picked the book apart. It wasn’t wrong, but it wasn’t right. I was telling everyone that the facts were there, but were like a jungle, like pick-up sticks. If you tease one out, the others will fall.

It got back to Jan, and he ran into me at the YMCA, and said, ‘I hear you know something about facts.’ And I felt stupid. I realized this was the new journalism of the 1970s. Looking for the truth of the matter is sometimes more important than the fact of the matter. The chaff falls away when you sift the wheat. And, well, you know, I have a real history of being wrong.

Four incarnations of The Improbable Rise of Redneck Rock later, Smith admits that memory is a funny thing. “It skips around like a rock across water over the years. Today we know that Jan Reid was really important to what we were trying to do,” he said.13

Many magazines and newspapers were covering Austin music, the Austin Sun and Picking Up the Tempo among them, with writers like Chet Flippo, Joe Nick Patoski, Joe Gracey, and Townsend Miller covering the front lines of the new sound. But Reid’s The Improbable Rise of Redneck Rock was the only book. And that book served to confirm that this new sound was a reality.

Joe Nick Patoski has reviewed or blurbed each edition of the book. He said, “I wrote two reviews of the book in the Austin Sun. The first (1974) was glowing. The second (1977) received a less kind review. As ambitious as it was, I said that Jan got it wrong. He did not see what was going on. Now, I can look back and say that it is as close to the bible as anything that has been written. There still hasn’t been another book that has tried to cover that subject to that degree—the country/rock/progressive/whatever-you-want-to-call-it shift.”14

Several books have been written about that “shift” in Texas country music history in recent years. Travis Stimeling, an ethnomusicologist at West Virginia University wrote Cosmic Cowboys and New Hicks (2011, Oxford University Press) and Jason Mellard, cultural historian at Texas State University, authored Progressive Country: How the 1970s Transformed the Texan in Popular Culture (2013, University of Texas Press). Later editions of Bill Malone’s Country Music USA (2010, University of Texas Press) add a section about the Austin music scene. Malone’s original book had been the product of his early-1960s dissertation while a student at the University of Texas.

Writers and musicians who witnessed that scene agree that Jan’s book made a difference. It imprinted the legitimacy of this new sound that everyone had been talking about, and journalists had been chronicling in other, less permanent forms. There is something important about books. They flourish and last.

Smith added, “Jan’s book was the first. Jan was the first. He was John the Baptist of Austin music books. Bill Malone had done a history of country music, but it was broad. Jan was writing about our home. And he got it. And I was being pissy about the order of information, but Jan was the one who saw that what we were doing was real and might have some staying power, and he wrote about it and put it in a hardback book. And it’s still out there. And we still get excited about it.”15

The Early Years

A succinct profile of Reid’s early background can be found in his introduction to The Improbable Rise of Redneck Rock. He expands on his background in a 2000 collection of essays, Close Calls, and his 2002 memoir, The Bullet Meant for Me.

Jan Reid was a native Texan, born in the Abilene hospital in the spring of 1945. When he was four, his family moved to Wichita Falls, where he grew into what he described as an “accidental journalist.”

“I was a reader growing up in North Texas,” Reid wrote. “It beat hoeing the flowerbeds.” J. D. Salinger’s The Catcher in The Rye brought his first experience of staying up all night to finish a book. A college freshman at his hometown university, he admits having little in common with the protagonist, but was at once struck by the phrasing and dialogue and was “moved to my bones.”16

Reid wrote often of his youth in a hard-knock region of Texas; his father, a refinery worker; and his mother, the daughter of a tenant farmer. He said, “The Depression had bitten a mean chunk out of their youths,” describing his parents’ functional concept of college. “The point was to come out and be able to make a living.”17

After several false starts in college (football coach, economist, lawyer, historian), Reid decided he wanted “a glimpse of the 1960s Promised Land, California.” So, he joined the Marine Corps Reserves. “I woke up with my head shaved in San Diego, hearing the warbling menace of drill instructors and drum beat of marching boots and thought, pal, you’re going to make some mistakes in life, but this one’s a doozy.”

The reserves saved him from the draft, for which he is still grateful, and after sitting out the Vietnam War defending Abilene, Texas, Reid continued plodding through college, and working construction and other odd jobs, until finally in his last semester, he signed up for a creative writing class. “I finally found something I wanted to do. Something I thought I could do,” he said.18

A young Larry McMurtry, only nine years older than Reid, was setting the woods on fire with his novels and essays, only twenty miles from Wichita Falls, in Archer City, Texas. McMurtry made this writing dream seem doable. His characters were recognizable. His books were about familiar ground. And people were reading them. Most impressive of all, his books were being made into movies featuring some of the big stars of the day.

Reid wrote, “My stock was rooted in the same red soil, though my elders were farmers and wildcat oilmen, not cattle ranchers. I didn’t meet McMurtry for another twenty years and have never been able to say I know him. But it was impossible not to be influenced by him.”19

Reid was twenty-three when he graduated from Midwestern State University and left Wichita Falls. He moved to Dallas, stumbling around a city he described as stifling. He found work as a copywriter for an insurance agency and spent his nights working on a novel about an unhappy young man driven to political assassination. The subject was still a fresh wound in Dallas. It was 1968 and had only been five years since the Kennedy assassination. He admitted, “Thank God it never saw print. But I learned something important. Trying to write a novel made me feel uneducated. I hadn’t read enough to be a writer.”

In the summer of 1970, Reid moved to Austin to begin graduate school in American Studies at the University of Texas. After a year, he was an academic burnout, slogging through the novels of Henry James. “The books that moved me were McMurtry’s essays, In A Narrow Grave, and the Willie Morris memoir, North Toward Home. John Graves’s Goodbye to a River was right up there with them. They had relevance.”20

Reid recalled the department chair inviting some grad students to his house one evening and pulling him aside. Bill Goetzmann, a Pulitzer Prize-winning historian of the West, said to Reid, “Get out of this while you still can.” The night wore on, and several shots of vodka later, Reid sat on the sofa arguing the merits of Texas fiction with this noted historian. Goetzmann believed there was little in Texas worthy of mention. Reid made an impassioned case for McMurtry’s Leaving Cheyenne and Bill Brammer’s The Gay Place.

“Boy, I told him good,” he said. “Then I flung open the door planning a masterful exit and walked right into the closet.”21

Despite a few wrong directions along the way, finally, with a bachelor’s degree from Midwestern, and a master’s degree from the University of Texas (1972), Reid set out to chronicle and defend Texas culture, landing in a celebrated career of tilting at windmills for nearly five decades.

He made his way through the sports desks at a couple of small-town weekly newspapers (the Mount Pleasant Tribune and the New Braunfels Herald-Zeitung). But he wanted more. A visit with the editor of Texas Parks and Wildlife redirected him to the front door of a startup magazine called Texas Monthly that was said to be seeking young and hungry contributing writers.

Jan Reid and Texas Monthly

Music was not the only art to redefine itself in Texas in the early 1970s. 26-year-old Michael R. Levy had graduated from the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania and earned a law degree from the University of Texas. Along the way, he had been a stringer for United Press International and was on the desk when Charles Whitman climbed the University of Texas tower and found his 96 minutes of infamy. Levy worked at the Dallas County Jail, drove a taxi, sold advertising for Philadelphia Magazine, and worked on Texas Senator Oscar Mauzy’s staff. And in 1973, he started his own magazine.

I wanted to create a community magazine. And the community was Texas. The neighborhoods were Dallas, Houston, Wichita Falls, San Marcos. . . . A community where everybody knows everybody. And I figured that if we put out a magazine of national quality for the city/state of Texas, we'd have a shot at success. We committed to make a difference in Texas journalism and in the nonprofit arena. I wanted to create a family culture among our staff, and build a strong literary connection. . . . It all worked. If you look at when Jan began working at the magazine, and the people who came together at that time, it was sort of like God wanted there to be a magazine with this great assemblage of talent. Not only were these people incredibly talented, but they also had great hearts and souls. I wanted them to be staff writers, so they could concentrate on our stories, instead of worrying about their next gig, like a freelancer has to do. And we gave these writers the opportunity to do long form journalism.22

Texas Monthly won a National Magazine Award in its first year and has gone on to earn thirteen more, putting it on a level playing field with the The New Yorker, Esquire, The Atlantic, and Vanity Fair. And in February of 2023, the magazine will celebrate its fiftieth anniversary.

Levy reminisced, “If I knew then what I know now, I wouldn't have done it. And even if I tried to do it, I couldn't. It was, again, the perfect time. Just perfect. Austin was such a sweet town to start a magazine. That era of The Gay Place was still in the air. Postage rates were cheap. Paper and printing were cheap. If I tried it today, I'd be bankrupt in the first six months. But back then, we were so small, my printer forgot to send me a bill.”23

Before long. true to Levy’s dream, the early Texas Monthly writers were a close-knit group, Reid recalled, “complete with family drama.”24

Romance, influences, mentors, and lifelong friendships grew from those early years of Texas Monthly. Michael Levy writes in the foreword to The First Five Years: The Best of Texas Monthly, “This volume contains only a sampling of what I consider to have been some of the best journalism published anywhere.”25 But Reid’s initial introduction to Texas Monthly was less than welcoming.

I went up to the office, and Levy came out and snatched my file from my hand, and just left me standing there. And that was it. I had a high school football game to cover that night, so I went back home to New Braunfels. But soon after that, I got a note from Greg Curtis. He was the number two over there, behind Bill Broyles. I knew who they were. He and Broyles had been star students of Larry McMurtry’s at Rice [University]. They had landed in the editorial positions of starting up this magazine for Levy. Broyles had been the publicist for the Houston school district, and Greg had been out in San Francisco running a little printing shop. Anyway, Greg read my file, and sent me a note that said, “What you left here, we can’t use for various reasons. But if you have any other ideas, get back in touch with us.”26

Less than a week later, his first Texas Monthly story literally ran through town. Reid recalled his big break. “Some losers had held up an icehouse in San Antonio, and immediately ran a red light and got the police after them. By the time they got to New Braunfels, literally every cop within 45 miles had entered the bullet-riddled freeway chase. The robbers missed a curve and rolled over in front of the construction site for the new Canyon High School. They had a Bonnie and Clyde scene with more than 120 bullet holes in the driver’s door and a couple of dozen shots into the new high school building.”27

The bad guys died. The good guys headed back to the New Braunfels city hall to get their stories straight, an evening that allegedly turned into a poker and bourbon party lasting well into the morning. Texas Monthly published Reid’s first contribution in their third issue: “The Get Away That Didn’t Last” (May 1973). This would be Reid’s first of more than fifty major stories and features to grace the pages and cover of Texas Monthly through the years.28

Six months after his Texas Monthly debut, “The Coming of Redneck Hip” marked Reid’s first longform music feature in the November 1973 issue. He wrote of this new country-rock hybrid sound that was coming out of Austin, chronicling the migration of seasoned musicians flocking into the capitol city.

As he wrote about the first financial music festival disaster that was the Dripping Springs Reunion festival in 1972, Reid knew he was onto something more. He introduced Armadillo World Headquarters owner Eddie Wilson to a broader audience than the young hippies and old cowboys who stood side by side in the old armory building-turned-music hall in Austin.

[Eddie] Wilson and his music business colleagues stress that any Austin music boom must remain localized. The creation of a music center in Austin would bring millions of dollars into the local economy, millions that would wind up in the pockets of Austin musicians, technicians, artists, and publicists struggling to get by now. Even the environment would benefit. According to Wilson, the music industry, unlike others that a growing Austin might attract, “doesn’t pollute and it doesn’t get in the way visually; about 50 million dollars could be put into the Austin music business and remain invisible.” The stage has been set very nicely, so why not continue? Thus, the music businessmen proceed, caution thrown to the winds.29

Reid recalled in 2019 the cultural and artistic shifts emerging in Austin during this particularly heady period.

It wasn’t just the music. Austin was becoming a mecca for writers, artists, musicians, poets, and even politicians. There was a real scene growing here. There is no doubt about that. This new voice was developing. The first time I heard this new music, Michael Murphey—Michael Martin Murphey—was playing on this slope out in the cedar breaks, called Hill on the Moon. They had a stage, and a good sound system and people could just walk up. They had a poetry reading first, and that was not too good. Then Murphey came on stage with his band and did “Geronimo’s Cadillac,” and it was electrifying. I’d never heard anything like it. Except that I had. It was country, it was gospel, it was rock and roll. It was electrifying country, but closer to rock and roll than Nashville country. It was Austin’s own voice.30

As Reid wrote about Murphey on that stage, he was describing an entirely new sound coming out of Austin. “It was like somebody turned a Baptist church into a country-western honky-tonk invaded by hippies. The longer they played, the more evident it became that this was a music in which the instruments took a back seat to the lyrics.”31

Reid’s Texas Monthly feature painted a vivid picture of this new moment in music, describing it as “Redneck Hip.” A few months later, in the spring of 1973, Reid began writing a book about this new music scene.

The longest-tenured editor of Texas Monthly, from 1981 to 2000, Gregory Curtis was a senior staff writer in 1974. During this interview he was surprised to hear that any controversy had arisen in the wake of Reid’s book, and much to say on the subject. “I don't know what is controversial about the book. I reread it not long ago, when it was reissued (TCU, 2021). I was really impressed, again. Surprised would be the wrong word, but I really did like it.”

In 1974, Jan knew this was a book when nobody else really did. And he wrote it. He reported it and wrote it, and he got it published. And I remember thinking, I'm not sure I would do that, but now I know it was exactly the right thing to do. It was what was going on at that moment. It's a picture of Austin. Probably nobody cares about B. W. Stevenson anymore or some of the other people. I don't mean to dismiss them, but at the time, they were really doing things that got people's attention. Anyway, my hat was off to Jan as I was reading the latest edition. It is, and it was, a book that needed to be written. . . . As for what was in and what was out of the book, okay, you're going to write about the Austin music scene in the early ‘70s, or you're going to write about the San Francisco music scene in the ‘60s, you must make choices and you make your own choices. And other people are free to disagree with them and think, oh, yeah, well, where is this band or that band. But unless it's some huge omission, for instance, you write the ‘60s San Francisco book, and you never mentioned the Grateful Dead, which was the central core of the scene, the writer can pick and choose. And that's exactly what Jan did. And people might think, well, so and so was important. Why doesn’t Jan talk about that person? Well, okay, fine. I don't think it's the totality that matters. When I was reading the book, I felt like I was right back in that era again. And back then, we all had to pick and choose who we went to see. If you go out to see X, you are going to miss Y. That’s the choice you had to make.32

Another Texas Monthly veteran, Stephen Harrigan, considers Jan’s talents.

Jan was like me. He was both a fiction writer and a journalist. One of the good things about journalism, particularly magazine journalism, is that it draws you into areas you didn't think you were going to know anything about or even care anything about. And you soon discover that you can get interested in anything and be passionate about anything, because once you look under the hood of any kind of endeavor, you see how fascinating it is and how interesting the people are. Jan had the kind of omnivorous curiosity about everything.

First and foremost, he was a writer. He got excited in the same way all of us do. You start to realize there's a story here, these are interesting people, this is an interesting field of expertise that I can help illuminate and help people to understand. When he started writing about Austin music, even though music writing was sort of foreign to him, he quickly discovered that he had as much right to write about these people as anybody did because he had something to bring to it. And from the beginning, Levy and Curtis and Broyles wanted Texas Monthly to be considered a writer's magazine, meaning that the writer's voice was paramount in terms of what we were doing. And one thing Jan had, that is either there or it's not there, was that writer’s voice.33

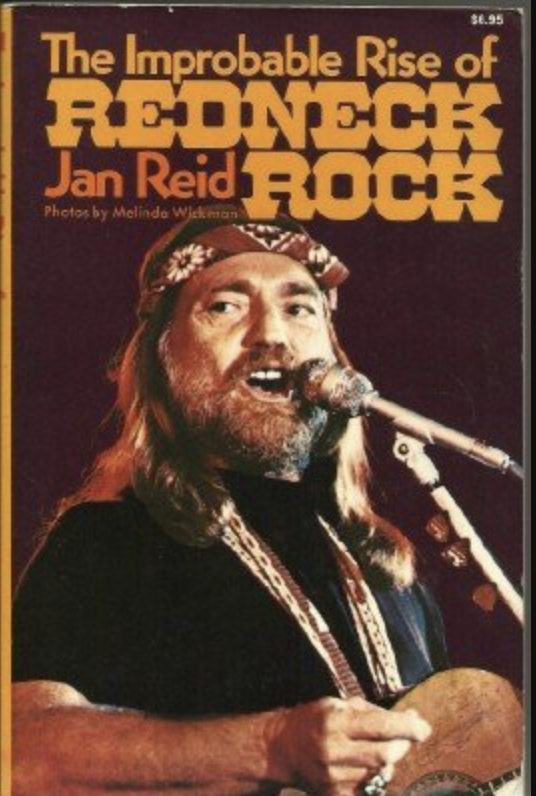

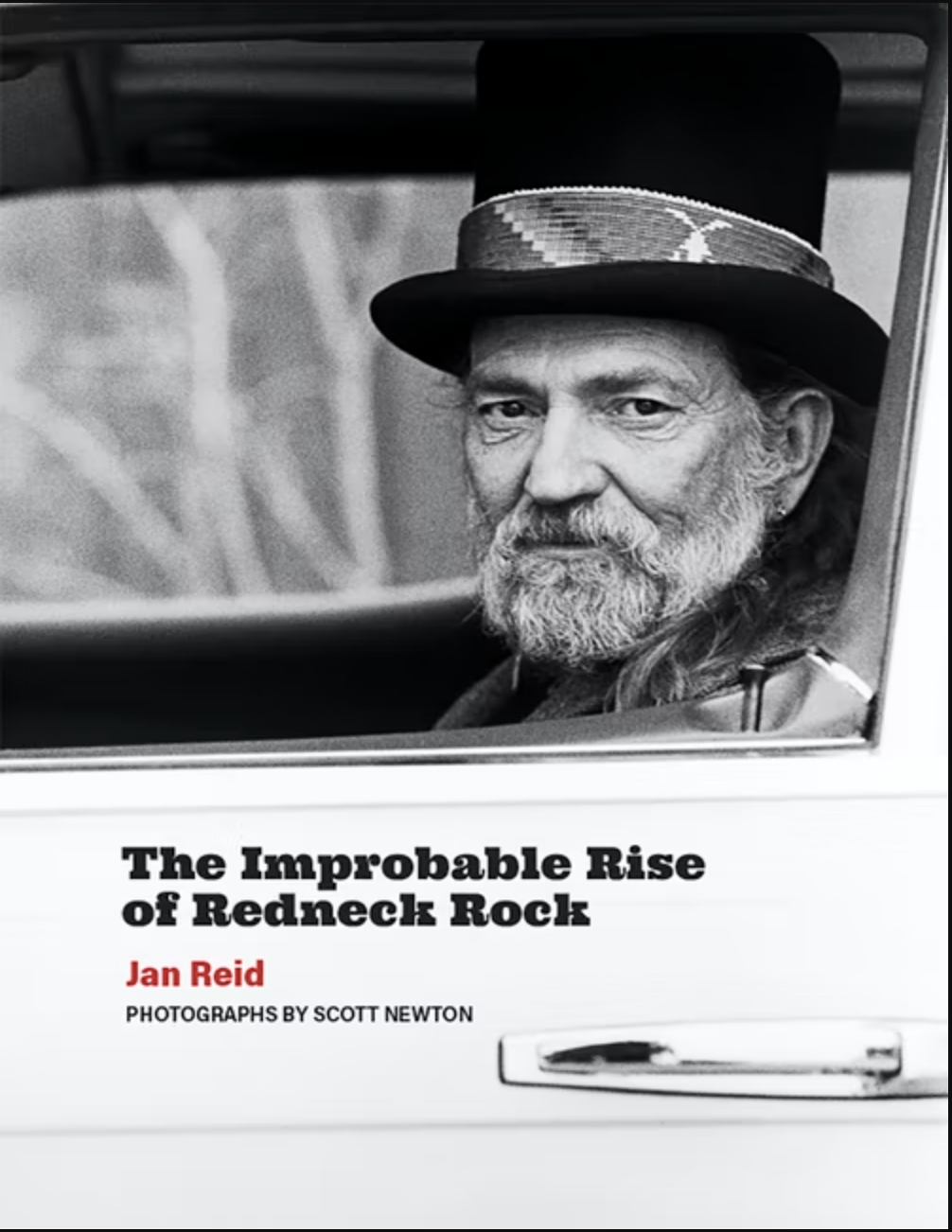

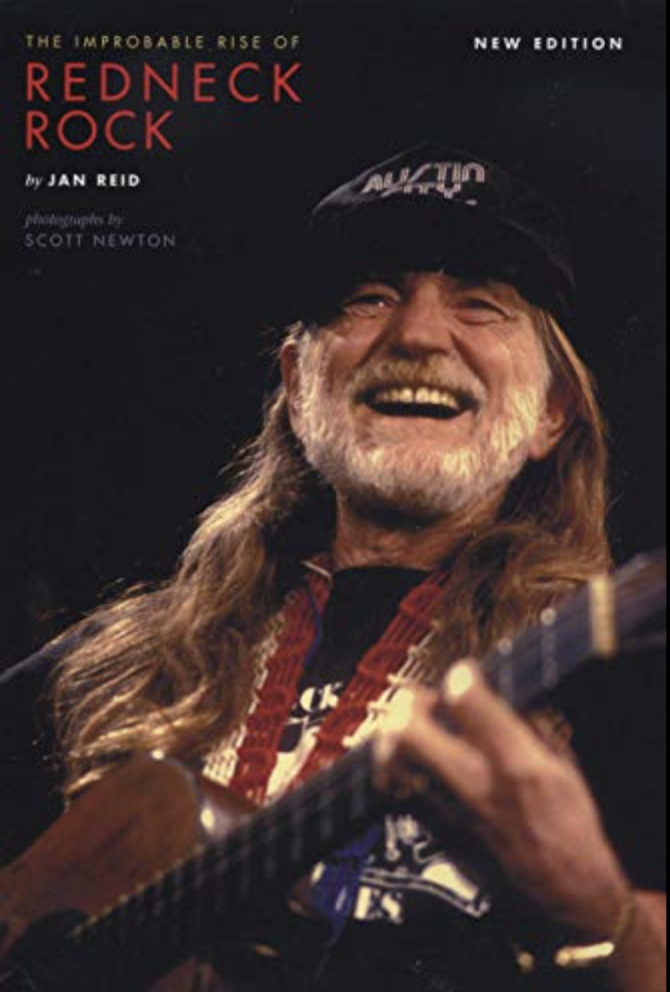

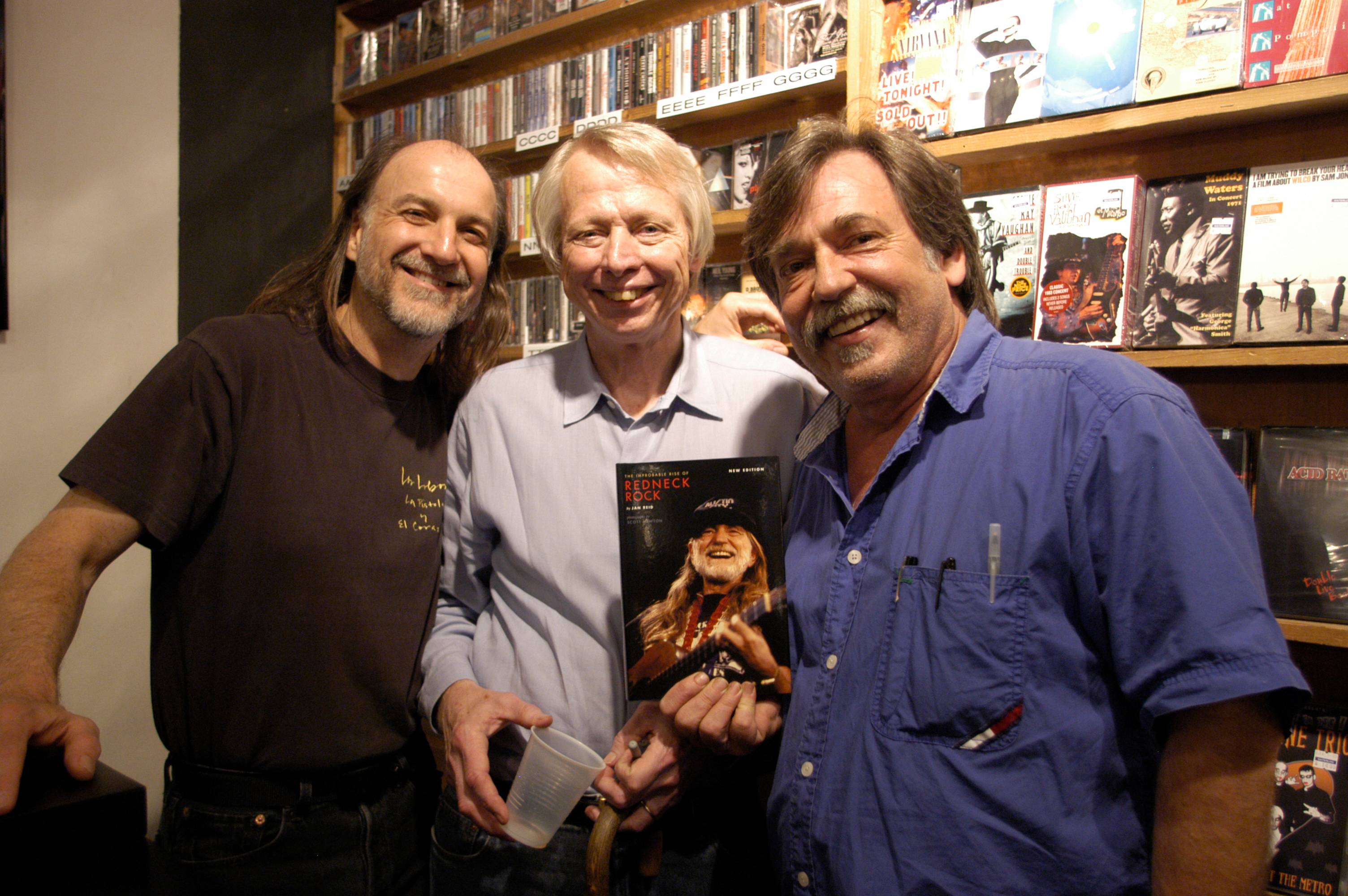

Despite whatever controversies have come and gone, The Improbable Rise of Redneck Rock has withstood the test of time and several incarnations. Heidelberg Press dissolved and Da Capo released a paperback edition in 1977. In 2004, the University of Texas Press issued a thirty-year-anniversary edition with Scott Newton pictures and substantial additions to the manuscript, followed by the latest edition with additional commentary published in 2021 by TCU Press. These resurrections of The Improbable Rise of Redneck Rock have proven it to be among the most definitive studies of this influential moment in Texas music.

Cory Lock writes in her article “Counterculture Cowboys: Progressive Texas Country of the 1970s and 1980s,” “These long-haired, bell-bottomed cowboys also explicitly articulated liberal political leanings. Jan Reid calls their work, ‘a songwriter’s poetry of homecoming, celebration of nature and intelligent soul searching.’”34

Archie Green presumes to explain in “Austin’s Cosmic Cowboys: Words in Collision” why Jan Reid coined the term “redneck rock” for his book. Green writes that “coming from a blue-collar, Wichita Falls family, Reid chose ‘redneck,’ a synonym for ‘clod,’ to describe Austin’s exciting fusion of orthodox country and high-energy rock music.”35

Whatever the reason for Reid’s title of the book, one only needs to read the blurbs on the dust jackets of the various editions of The Improbable Rise of Redneck Rock for an understanding of its importance to artists, journalists, and historians. Kinky Friedman writes, “Ever wondered why God chose Austin to be the live music capital of the world? Read this book.” In a review for GQ magazine excerpted for the book cover, Robert Draper, another Texas Monthly veteran, writes, “Reid’s book is a classic, and its prescience is a thing of wonder. Today there are literally hundreds of performers who owe their sound if not their very existence to the curious amalgamation Reid captured in his book.”

John Spong began his career as a fact checker at Texas Monthly and has worked his way up through the ranks. Today, he is a senior editor focusing on popular culture, and hosts the magazine’s music history podcast One By Willie. He describes Jan’s place in the Austin music scene.

Austin was having this weird moment where it was the coolest place on earth. And Jan’s book brought attention to Austin from beyond the city limits. Jan was here, and he captured it. Recently, I was doing a lot of Willie [Nelson] research and went back to that first article. I realized that Jan was right there at those fabled first shows. It’s a huge part of the magazine’s success that we were in those moments. Maybe they did not all reach the level of Willie or Jerry Jeff or Michael Murphey, but at that moment, they were all on the same level doing the same thing. It changed Austin. It changed American music. Jan was there with the eye to turn it into a magazine story and then a book. He recognized how special it was while everybody else was just going back and forth from the stage to the bar, having a good time.36

Jan Reid and Austin City Limits

In 1975, KLRU, Austin’s public television station, transformed from a modest hand-me-down studio filled with outdated equipment and surplus office furniture to a state-of-the-art station with multiple studios and pricy equipment. The program director, Bill Arhos, began looking for new programs to develop and pitch to PBS. Years later, he told Jan, “I got the idea for Austin City Limits from reading your book.”

“What?” Reid asked.

Arhos replied, “What was the most visible cultural product of Austin? It was obvious. It would be like ignoring a rhinoceros in your bathtub.”

Reid recalled the show’s genesis. “They pitched a pilot with Willie that was taped on October 17, 1974. I was not there that night, but I had been at the actual first episode the night before, featuring B. W. Stevenson. There was something wrong with that recording, so they had to use the Willie taping as the pilot during the January pledge drive, and it was so successful that PBS signed on to produce a series.”37

Today, forty-seven years later, ACL is the longest running music series in American television history.

Jan Reid and the Paisano Fellowship

In February of 1977, three years after The Improbable Rise of Redneck Rock was published, Reid was awarded a prestigious Dobie-Paisano fellowship. Sponsored by the Texas Institute of Letters and the Graduate School at the University of Texas at Austin, the Dobie-Paisano Fellowship provides “solitude, time, and a comfortable place for Texas writers or writers who have written significantly about Texas. The retreat is on a 250-acre ranch about twenty minutes west of Austin. Here J. Frank Dobie’s ranch house becomes the writer’s home for six months, with a monthly stipend.”38

The judges that year were Texas Monthly editor Bill Broyles, American novelist Shelby Hearon, and publisher Bill Wittliff. Reid moved into Dobie’s ranch house in February of 1977 and spent six months there.

Paisano is really where I really learned to write for a living. I learned discipline and routine. It’s a great place. It was the first time I had ever been just free to figure out things. I learned how to garden. I went to the post office every day and swam in the creek. I learned that I was a morning person, creative-wise, And, through routine and patience, I learned a lot about myself and what I could do and how I worked. It was where I learned to work. And I got a lot done. Until they made me move out so Steve Harrigan could move in.39

Reid got to know a lot of people through his Paisano connection, among them, Shelby Hearon. In the Southwestern Writers Collection at Texas State University, correspondence between Hearon and Reid during his Paisano residency tells a story of a friendship that grew into a love interest.

After Paisano, she was working on the Barbara Jordan biography. She wrote a short book called A Prince of a Fellow. I guess it was about who she thought I might be, and then everyone thought that was who I should be, since I was her man-in-tow at the time. It turned out, I was not her Prince of a Fellow after all, but it was a good time. We got to know Barbara Jordan during that time. And I learned a lot from Shelby. She was a good teacher, and she thought she needed me to help her write nonfiction. She didn’t, but I hung around pretending she did.40

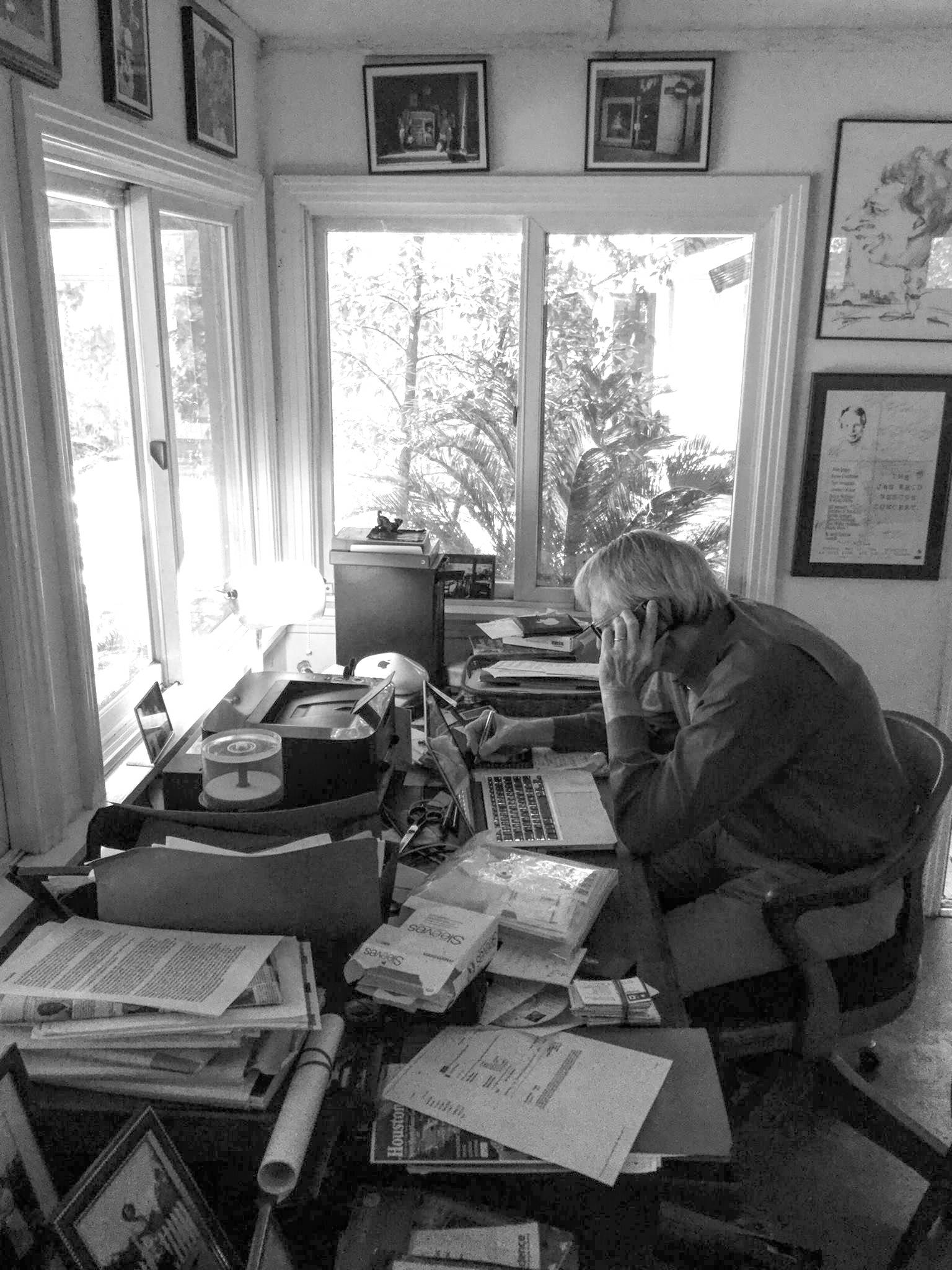

After The Improbable Rise of Redneck Rock was published in 1974, Reid continued to sculpt a prolific career at Texas Monthly and published several books, fiction and nonfiction, writing, it seems, about everything but music.

About twenty-five years after that book came out, someone asked me why I stopped writing about music. It hadn’t occurred to me that it’d been that long. I had written several novels, so I thought about it and realized that the reasons I had stopped writing about music didn’t make sense anymore. So, I started doing some short pieces. The first one was Lyle Lovett. I saw something new and different, but strikingly familiar in him. He opened for John Prine at the Paramount Theatre. Here was this crazy looking guy with that hair, playing country music with a cello. And he sounded a lot like Willis Alan Ramsey. I later learned that that Willis had been among his early influences.41

In 1998, Reid wrote a feature for Texas Monthly entitled “The Improbable Rise of Lyle Lovett.” They met for the interview in a Manhattan hotel on the day of Lovett’s seventh album release. Step Inside This House is a tribute to the Texas songwriters who had influenced Lovett; among them, Guy Clark, Townes Van Zandt, Steve Fromholz, Michael Martin Murphey, and Willis Alan Ramsey.

Lovett told Reid, “The first time I encountered these songwriters was reading about them in your book. I learned to play the guitar listening to some of these songs. For me, this record [Step Inside This House] is going back to the beginning. It’s kind of like taking stock and starting over.”42

Why Austin?

Why Austin? Why not Houston or Dallas or San Antonio for this renaissance? Reid attributed the explosion of the Austin scene in part to the fact that it had the largest college in Texas. Reid said that a university community always raises the level of bohemianism, art, and intellectualism. He added, “Texas is geographically convenient — between New York and LA. And it’s the seat of government — not just any government — the Texas seat of government. And Levy had that crazy dream and we all believed in him, and that somehow worked.”43

Craig Hillis, a renowned guitarist who toured and recorded for decades with Jerry Jeff Walker and Michael Martin Murphey, went on to earn a Ph.D. in American Studies from the University of Texas, with a natural focus on Texas music.

Jan was a writer’s writer. He nudged you. He nudged me. He could recognize excellent writing in many different theatres, whether poetry or playwriting. But most importantly, he recognized the strength and longevity of a song. He loved the integrity of the song as a work of art and, to some criticism at the time, he focused on the songwriters of that time who were carving their own niche in the music world. . . .

Jan saw that Murphey was stunningly prolific, Steve Fromholz was magical, Bobby Bridger was underrated, and Willie was the Next Big Thing. Jan recorded a lot of his interviews and when he would write what they said, some of his subjects didn’t like what they heard. His interview with Murphey was stunning because it was spot-on. He repeated Murphey verbatim, and Murphey sounded like a screaming hippie. . . .

Jan was never afraid to get his hands dirty for his art. How many writers will take a bullet for their passion and live to tell about it? But back to The Improbable Rise of Redneck Rock. American civilization was changing course, and we were learning to chart our own way. The ‘60s were a politically-based radical explosion, with the Vietnam War and protests and such. The ‘70s were more like what the ‘60s wanted to be, a time of cultural explosion. The passion of the ‘60s grew into a celebration of peace, love, brown rice, and idealism in the ‘70s. And this newly discovered independence coupled with energy of youth manifested in these singer-songwriters who could grab a guitar and sit on a stool and play music all night long. And people would listen to the words and recognize the poetry. Fromholz did it. Murphey and Walker did it. Rusty Weir put his drums in storage and climbed on a barstool with a guitar to sing for the song. And Willie did it— he grabbed the world by the cojones as far as we were concerned.44

Hillis added, “In his book about Texas music history, Gary Hartman said Redneck Rock is not a scholarly book. My response is that neither is Catcher in the Rye. But Jan did his homework. And sometimes that homework was drinking beer and standing around a mythological campfire till the wee hours, taking notes.”45

Novelist and musician Jesse Sublett is best known for his rock trio, the Skunks, with Bill Blackmon and Eddie Muñoz. Muñoz left town and Jon Dee Graham replaced him on guitar, forming the definitive Skunks sound. They became the foundation of the punk/new wave scene in Austin in the 1980s. Jesse was a longtime friend of Reid’s.

I wanted to be in the glam rock scene in Austin. But progressive country was eating that up. It was kind of annoying to me. All the country cosmic cowboy stuff that was happening. I grew up in Johnson City, Texas, where if you had long hair, you were “hippie” to the “shitkickers.” That was our major community conflict. So, when the hippies started wearing cowboy clothes and listening to country music, at first it was ironic and kind of funny. I thought a lot of it was a put-on like, hey, look, we're absurd here. But then it started getting serious with the whole cosmic cowboy scene. I was not a fan at all of it. They were playing country on the FM rock stations. It was taking over. . . .

But it’s crazy how fast things just totally spin around the cycles, because when something's really happening, you feel like, well, this is it. This is the music thing. But really, this is the culture we have in that moment, and it's temporary at best. I think a lot of it had to do with the fans aging out of the music. You're having all these fans who are in college and then graduate school, but then in six years, those people have moved on. They've got jobs and families, and they're not going to clubs anymore. They’ve outgrown the music. Whatever the “thing” was has run its cycle. And I think that's what happened with the Redneck Rock or Cosmic Country music, or whatever we're calling it here. And the punk rock scene went through its cycle even faster. Our scene started in 1978, and it permeated the whole culture in Austin by the early/mid-‘80s. The city and the community didn't really have much infrastructure for live music and didn’t yet understand the economic benefits music could bring to town. The ‘80s brought South by Southwest to Austin in 1987, and that became the springboard for our music. SXSW did for us what Jan’s book did for the singer-songwriters.

I ended up becoming good friends with Jan because he was such a sweet soul. He was never a music cynic. I mean, he saw the irony and absurdity in what was happening, too. He had grown up in a West Texas town that was divided by musical tastes, as well. Jan’s book was really a big bag, wasn't it? Years later, those events and people took on a lot of weight and we could all see what how things came together. But back then, Jan was one of the first people to see that something was happening. He knew it was the beginning of something important.46

Jimmie Dale Gilmore was among Jan Reid’s closest musician friends through the years. Before The Improbable Rise, Gilmore had been a fixture in the Austin music scene during the 1960s. His band the Hub City Movers was the last house band at the Vulcan Gas Company in the first months of 1970, and they played the grand opening of the Armadillo World Headquarters on August 7, 1970.

We were doing real country music for a hippie audience. It was catching on. But I was looking for something I couldn’t find. First, I went to Lubbock and that’s when the Flatlanders happened. And then I went on to Denver and spent the rest of the ‘70s on a spiritual quest, in what could probably best be described as a cult. I wasn’t playing music then, but I was coming back to Austin a few times a year. Butch [Hancock] had moved here by then, Freda and the Firedogs were big. Marcia [Ball] and I became good friends. I always stayed with them when I came to town. The sounds of Freda and the Firedogs and the Flatlanders were a major departure, kind of a seminal thing in the unfolding of the Austin music story.

Jan recognized this scene that was coming together. It was just a bunch of free-will musicians coming out from different backgrounds and playing together. And when Jan’s book came out, people had a name for whatever it was that was happening, and could give it a launching point, but the thing was, Austin had a great music scene long before it was known for the Cosmic Cowboy/Redneck Rock thing.

The important difference was that this new music grew organically. It wasn’t the result of some hype or business model. It just happened that Austin had drawn so many creative talented people to one place at the same time—and not just musicians. Writers were creating a new slant on journalism. And politicians were mingling with artists. The timing of a lot of things came together. For that convergence to happen, a few people had to step in at the right time. Jan had a place to write it down and he did a great job of making sense of it. A lot of good music had been coming out of Austin before it became an outlaw mecca, and some of those artists already had national recognition.47

In fact, by the time they were “discovered” in Austin, Michael Murphey had a couple of hits under his belt. Jerry Jeff Walker came down to Texas behind hit covers of “Mr. Bojangles” by the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band in 1970 and Sammy Davis. Jr. in 1972.

And of course, by 1972, Willie shed Chet Atkins’s Nashville Sound, along with his blazer and razor, and came home to Texas to create an image all his own. He has continued to define the spirit of Texas music for more than a half century since his return.

Gilmore adds, “It was as though Jan and I were already friends when we first met. We had so much in common: musical taste, literary taste, politics, and sense of humor. That was the major part of it. It was like we were from the same tribe. Jan was a comprehensivist, as Buckminster Fuller would say. He understood the synergy and cross pollination of what was happening. He appreciated that the arts fed each other, and politics were a part of it, and the writers had a responsibility to capture it.”48

“It all happened so fast,” Reid recalls. “Looking back, Don [Roth] and I left a lot out of that magazine article. I was focusing on Austin. It had some flaws. There were great sounds coming from all over the state. Doug Sahm and Augie [Meyers] were happening in San Antonio, with the West Side Horns. Delbert [McClinton] was hot in Fort Worth. They were happening, too. I realized that the 2004 edition of The Improbable Rise of Redneck Rock needed to be more than just a re-issue. This uniquely Texas sound, a melting pot of culture was all around us, and I hadn’t given enough credit at the time for what a lot of people were doing in Texas music. That is part of the reason I wanted to write the Doug Sahm biography [Texas Tornado].”49

Jan Reid’s body of work can be described in four broad categories, with all paths leading to or from Texas: music, politics, sports, and literature. Reid’s life crossed paths with almost as many politicians as musicians. Politics played as much of a primary role in his writing as other components of Texas culture. He penned magazine features about Texas gubernatorial candidate Tony Sanchez and revered Texas legislator Bob Eckhardt; and wrote articles that grew into books recounting the tilt of Texas politics, caused in great part by Tom DeLay and Karl Rove.

Jan Reid and Politics

A genealogical study of Texas politics in the late twentieth century finds Reid swinging from several branches of the tree—and writing about those wild years when liberals ran free and ran Texas. Reid’s mentor, Billy Lee Brammer, was married to Nadine, who later married Texas liberal patriarch Bob Eckhardt, a strong legislator about whom Reid wrote one of his most reactive Texas Monthly articles.50

Reid’s longtime friend and romantic interest in the 1970s, Shelby Hearon, was co-writing the Barbara Jordan memoir (Barbara Jordan: A Self Portrait, Knopf/Doubleday, 1979) during the time she and Jan were living together.

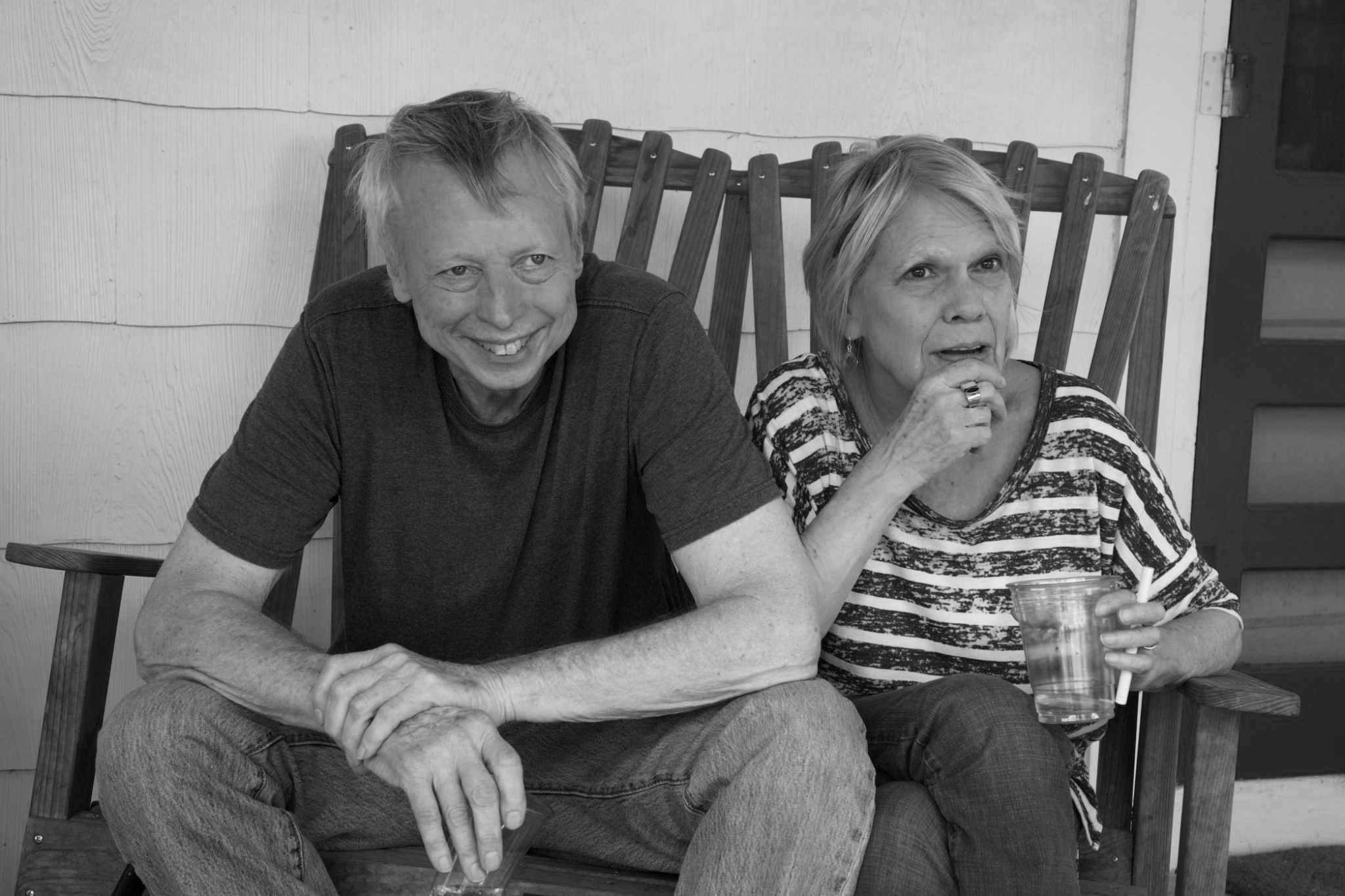

In 1980, Jan Reid was introduced to Dorothy Browne by novelist and former Dallas Cowboy receiver Peter Gent at a party. Gent introduced her as Dorothy Brammer, Billy Lee Brammer’s ex, but she announced that she was through changing her name to those of men, and from then on was going to use her family name. Jan and Dorothy soon realized that the rest of their lives were meant to be spent together. They were married on July 4, 1982, and were together for 37 years, until her death in 2020.51

Browne’s daughter, Lila Reid Vance, (who legally added Reid to her name to honor her stepfather) said, “Jan came into my life through my mom. I was eight when they got married, so I was about six when they started dating. I didn’t meet him at first, because I spent weekends with my dad, but when I did, I instantly felt comfortable with him.”

What really stuck with me was that they really had a wonderful love affair along with a very modern marriage. My mom worked hard, and Jan was home writing. He would pick me up from school and take me where I needed to go. They shared all the responsibilities like cleaning house, getting groceries, cooking. And I still think it was beautiful that they would have dinner together every night and sit and have these amazing conversations about what was going on in the world, or a new book that one of them had read—substantial conversations. That is rare these days. Jan and my dad were friends and would talk on the phone when my dad would call me. When I got married, they walked me down the aisle together.

When Jan died, I kept reading these tributes about him, and how he was so soft spoken and gentle and calm, and all these things. And I kept thinking that obviously, those people were never teenagers living in the same house with him. I tried his and my mom’s patience for a few years. When I was about fifteen, Jan and I were having an argument, and I told him he was ugly and stupid and boring. He quickly came back with, “I’m okay with the first two, but boring?”

She recalled this instance with a laugh, adding that, as teenagers will do, she outgrew that phase of rebellion, apologized for words he had long since forgotten, and she and Jan remained close throughout his life. “After my mom died in December of 2019, Jan and I pledged that we would go out to more concerts and do things together. I was newly divorced, and he said he would be my wingman. He really helped me through that time. We went out to see Terry Allen, and then we saw Delbert McClinton at the Paramount on March 7, 2020. The next week, everything shut down with COVID, and he died in September of that year.”

When he passed away, he willed his home, and his beloved collie, Biscuit, to Lila, which she says, tearfully, “was life-changing for me.”52

When she married Jan, Dorothy Browne had been working for the Texas Civil Liberties Union. Ann Richards was elected Texas State Treasurer, and Dorothy went to work managing correspondence and researching policy for Richards. She followed Richards’s trajectory and was named associate director of the Texas Criminal Justice Division-Office of the Governor by newly elected Governor Ann Richards, with whom both Dorothy and Jan developed a longtime friendship. And that friendship led to his definitive biography, Let the People In: The Life and Times of Ann Richards.

“It’s hard to say where that book begins,” Reid said. “Ann was 47 the first time I saw her in 1985. She had just come home from rehab, ‘Whiskey Tech’ as she called it. We became good friends. When she died, Evan [Smith] called and asked me to write the memoriam for Texas Monthly. That surprised me because I was not one of [Texas Monthly’s] political writers. But I was her friend.”54

That article led to a rich, full-bodied story that is as much as story of twentieth-century Texas as a biography of a leader. Reid spent more than three years researching and chronicling this epic journey. “The University of Texas Press came up with the money and asked for 80,000 words. 160,000 words later, the book was pretty much done at something more than 450 pages. I am sorry I didn’t get to do more about the New York years. But it was already twice as long as we had expected. In the manuscript, I was on page 200, and had not even gotten her to Dallas yet. David Richards, her former husband helped a lot. Bud [Shrake, Richards’s longtime companion] got sick before we had a conversation about this, and he was racing to finish his last novel,” Reid recalled.55

Despite Reid’s second thoughts about what he left out, all that he managed to squeeze into the book makes for quite a story. Reid’s fiction writing talents coupled with Ann’s not-so-storybook life make for a biography that is hard to put down. More than a biography or memoir, this book is as much about the Times of Ann Richards (1933-2006) as it is about the Life of the former governor. Reid’s Texas roots, cultural instinct, and political savvy are evident throughout the project.

Jan Reid and the Culture of Texas Monthly

Longtime Texas Monthly editor Greg Curtis said, “Jan was writing for the magazine and had assignments for the magazine from the beginning. And then for a while he was on the staff. But Jan did what Jan did. He wrote what interested him. He found stories that he wanted to do. If you had a story that you wanted done, you could propose it to Jan, and maybe he'd like it, but maybe he wouldn't. He knew what was in his wheelhouse. The stories he did are the stories he wanted to do and knew he could do.”

We all had the same goal, which was to write well and to write about this region, about this state. So, we weren't directly competitive because there was no reason to be. Instead, we were mutually supportive. If Jan was working on a story, it was very natural for him to ask questions. We all did. If he wanted someone to read this and tell him what you think, it was just very natural. . . .

In those early days, Bill (Broyles) and I called ourselves editors, but we hadn’t really edited, and we hadn’t even written to that degree. It was a performance at first. We had Billy Lee [Brammer], and he had edited. He was a surprisingly good editor. He did some good work on some of the stories that came in that needed work. So, his contribution to the magazine went beyond the few stories he actually wrote for us. He brought an internal presence of editing other people’s work, which isn’t recognized in that his name is not on the piece in the final edition. But Billy Lee was important to all of us that way. And he was likeable and funny. But he was hopelessly addicted, and in the end, that killed him.

We didn't think about we were doing at Texas Monthly beyond the fact that we wanted to do the best we could. At thirty-nine, Gary Cartwright was a much more established writer than Jan or me or Bill Broyles when the magazine began. When Gary joined the staff, it gave us all a lot of credibility. Gary and his wife, Phyllis, and Jan and Dorothy became lifelong friends. Gary and Jan were mutually supportive as professional writers, and that grew into a very deep and valuable friendship for them both. We all developed friendships that lasted through the decades. Steve Harrigan was there. Bill Broyles, Richard West. I am still very close friends with them. And of course, Jan. Jan and I had something beyond the magazine. We worked out for years at Richard Lord’s Boxing Gym. It was another thing that cemented our friendship.56

Jan Reid, Sports, and Friendship

A study of Jan Reid without a mention of sports and sports writing would be incomplete. Sports have long been a part of his life, and nearly his death. His third published book, Vain Glory, was a three-part study of Texas football: the myths, the vanity, and, yes, the glory of high school, college, and pro ball culture.

W. K. “Kip” Stratton met Reid in 1987 and they were close friends until he died. “I considered him my best friend,” Stratton said. “I was working on the Ponca City News in Ponca City, Oklahoma, and had begun to sell magazine articles to Sports Illustrated. I knew about Jan from his Texas Monthly articles. I knew he had been a sportswriter for a small newspaper when he sold his first story to Texas Monthly.”

That crowd of unknowns who revealed themselves in Texas Monthly intrigued me as a reader. Here were these incredible writers who found their voices while working on that magazine. And Jan wrote about a lot of things that interested me. One day I was in Stillwater at a bookstore as they were unpacking a small press book by Jan called Vain Glory. I went home and devoured that book and thought, wow! This is an important book. It predated Bissinger’s Friday Night Lights by a few years but was sort of the dark side of the moon view of that whole thing. It was about Texas football in a time when high school, college, and pro ball weren’t what they used to be. They were all sort of down. I found that interesting. I knocked out about a thousand words about the book, and sent it off to Sports Illustrated, and they bought it. The editor I was working with said, “Yeah, we’ve had that book around here and we thought we wanted to get it reviewed but no one really wanted to take it home because they had other things going. Suddenly your piece showed up and boom. You’re good.” And with that story about his book, Jan earned me about a month and a half of my salary at the Ponca City News. So, I was indebted to him from the get-go.

We wrote back and forth in those pre-email days and talked on the phone, and he invited me down to Austin. A few months later, I swung through Austin after a trip to the Big Thicket on an assignment. Jan and I met for breakfast at the Nighthawk on Riverside. From that day, Jan did so much for me in addition to being a friend. He introduced me to two agents I’ve worked with. He opened a door for me at the University of Texas Press with the Grover Lewis book and agreed to sign on to help me write it. He opened the door for me at Texas Monthly and introduced me to a lot of people, including Larry L. King and Gary Cartwright, and Bud Shrake, all of whom were big deals for me. . . .

Jan never intended to be a music writer. He had a lot of interests. He was obviously interested in sports. But he was interested in fiction more than anything because, like all of us, he wanted to find some combination of Ernest Hemingway and John Steinbeck, and maybe a little Kurt Vonnegut. What writer doesn’t say, “Wouldn’t it be cool to write novels like that?”57

His stories of a young Roger Clemens (1991) and an old George Foreman (1995) were both selected for publication in Best American Sports Writing anthologies in their respective years. “Armed and Considered Dangerous,” the story of Clemens, led with, “The only thing scarier than facing a great pitcher is facing a hothead like Roger Clemens.”58

Reid’s story about boxer George Foreman comes near the end of the fighter’s career, just after he had fought Michael Moorer to win his second World Heavyweight Champion title on a fluke knockout in the tenth round. It was almost as much a fluke that Reid got to write the story about Foreman’s comeback. “There was something major about Foreman,” Reid remembered. “When he won his title back, [Gary] Cartwright would have been the natural one called on to write this story. He had written about him twice before. But he was on vacation with his family in Europe, so I quickly spoke up and got the story, and found myself riding around New York with the Champ. It was very fun.”59

Reid added in Close Calls, “[A]nd of all the distinguished words that have been written about the boxer, this piece was selected as the basis for a TV movie about him.” Reid continues, “I had hoped that George would retire and go out on top, but he chose to continue fighting, and the erosion of his skills began to reflect his age. When a mediocre youngster named Shannon Briggs was awarded an outrageous decision over George, I was glad—not because I feared for his health. It was a fight fan’s reaction. I just couldn’t stand to see him with nothing left but his jab.”60

Reid’s interest in boxing, which he admitted to being a “vice,” is one that dated back to his youth, and led to a trip to Mexico City, and a near-death shooting. Reid, along with three other Texas Monthly friends, went to Mexico City to see Jesus Chavez, who had been a contender for the super featherweight title in the States but had been made to leave the country. He was slated for a pseudo-comeback fight, albeit for 95% less than he brought in fighting in the States. Reid had written “The Contender,” a major feature about Chavez for the April 1998 issue of Texas Monthly. Aside from the story, Reid and Chavez were close friends. “I think of him as a son,” he said.61

Jan Reid and The Bullet

Shortly after “The Contender” was published, Reid mentioned that Chavez was going to be fighting on an upcoming weekend in Mexico City. John Spong had been the fact checker on the Jesus Chavez story. Mike Hall was Reid’s editor on the story. John, Mike, and John’s then-roommate, David Courtney, (who is now the magazine’s humor columnist, “The Texanist”) all ran around together. Spong had a friend with an apartment in Mexico City. And they all wanted to go to the fight.

Spong says, “I remember being really thrilled with myself. Going to the boxing match with Jan Reid was like going to the bullfights with Hemingway. We were going with the guy who had written about George Foreman recently. And boxing had mattered so much to him through Richard’s Gym.”

We got down to Mexico City and settled in at my friend’s apartment. He had left us a note with the key and specifics about the house and told us to ‘stay out of the green cabs.’ It was that plain. But we didn’t quite get it.

The first night we checked out the mariachi bars on the big plaza. Then on Saturday, we went to the fight and then back to the Plaza. David bought a goofy fedora or Panama hat at the flea market. I bought a little marionette. We looked like tourists. As we were leaving, Mike and Jan bought another six pack of beer. I don’t remember getting into a green cab, but we got into the wrong cab. David and Jan and I were in the back seat and Mike was in the front seat next to the driver. We knew the way back to the apartment, and he felt like we were getting off the path. We were talking in the back seat, when Mike said something like, “This is not where we are supposed to be.” Our cab stopped abruptly, and two men jumped out of a car behind us and climbed in our car. The fact that it was a very small car added to the chaos. A huge guy climbed in the back and sat on David’s lap, and another guy got in the front on top of Mike. The driver took off again. The front seat guy was the Alpha dog. He spoke English. He reached around and hit me in the face with the pistol a couple of times. Trying not to make eye contact I started looking out the window and trying to stay calm. I was convinced they were going to rob us and then everything is going to be fine, and it will just be another dumb thing we would have done. And nobody would get hurt. He robbed Mike and he started to rob Jan, but Jan began to argue with him. It was not going well. Jan was fighting back, verbally. Resisting. The guy took his wallet and Jan told him that was all he had. Then he took Jan’s watch.

We wound up in some little neighborhood. The cab driver pulled over. Dave whispered that when we open the door, we should all run for it. David and Mike opened their doors at the same time and Dave hauled ass as fast as he could. Mike couldn’t run because the front seat guy with the gun was right there on him.

I was telling the cab driver that he could not leave us there. Just let the robbers take our stuff and then take us back, I told him. But I don’t remember him speaking English, so I am not sure if any of that registered. Meanwhile, out on the street behind the car, Jan began arguing with the front seat robber and the bad guy threw a punch. Then Jan threw a punch back. And I thought, “Well, I guess I will have to get into this,” and went around to the back of the car.

I heard one shot and then a second shot. The second shot hit Jan. He was wearing a white long-sleeved shirt. He had told us he had gotten it in Mexico with Dorothy, and it was his favorite shirt. Maybe it was his wedding shirt. We had been talking about it all night. I was still thinking everything’s going to be fine. Nothing bad is going to happen. And then Jan went down.

I even said, “Dude, that was fantastic. They think you’ve been shot.” Jan shook his head, and said, “No.” I looked down, and the white shirt we’ve been talking about all night was covered with blood. The bad guys had all piled in the cab and left during the chaos. Dave ran back and said, “We have to go find help.” Mike sat with Jan. Dave and I split up and ran down the streets pounding on doors, looking for help. By then, it was one or two in the morning, so we didn’t have any luck.

We ran back to Jan and a guy with a medical bag who was just getting off work was helping him. He was an EMT. He helped Jan and then said that we must go to the American British Canadian Hospital— ABC. Somehow we got to the hospital and they immediately went to work on Jan. I remember Jan saying later that he was the oldest (by about twenty years) and he had to protect us. Mike was the next oldest, so he called Dorothy to tell her. He seemed to have fallen into the role of older brother.62

The bullet went through Jan’s left wrist, into his abdomen, and lodged against the vertebrae in his lower spine. Two surgeries in Mexico City, private jet flights from Austin to Mexico to Houston, emergency rooms, rehab centers, the famous Dr. Red Duke, and a trauma center dream-team later, Reid survived.

Gregory Curtis explained in a Texas Monthly story six weeks after the shooting that Reid is a freelance writer, and how that profession impacts the story. He wrote, “Unless he writes, Jan has no income. Most, but not all of his medical expenses will be covered by insurance. He faces a long period of little or no income during recuperation. He faces a lengthy rehabilitation whose final result is uncertain. If determination and hard work turn out to be all that is required, he will certainly walk again. A fund has been established for his benefit.”63

Upon reading those words, friends and strangers stepped up and helped. A $5,000 check from boxing promoter Don King and a penciled letter from a stranger stating, “I would like to donate this blood to Mr. Reid,” stapled to two receipt forms from the Gulf Coast Regional Blood Bank; a note from a woman who reintroduced herself as the red-headed girl who lived downstairs from him in an Austin apartment complex when he was in grad school, attached to a small check; and the list goes on. Dorothy was working for Garry Mauro in the Texas Land Commissioner’s Office at the time of the shooting. Reid said, “She had to take off to help me and Garry kept her on salary. Ann Richards helped coordinate things. Mike Levy did a lot. He was the one who connected us with Red Duke, the best trauma doctor in the country, who saved my life. Greg Curtis and Steve Harrigan started a benefit with a bunch of writers and musicians. I could never begin to thank everyone who was there for us.”64

Old friends and total strangers came out of the woodwork to lend a hand—and a few dollars—to the cause.

Classified in medical terms as an incomplete paraplegic, Reid regained much of his physical ability, walked with a cane, and went on to write some of his best work after the shooting. And yes, his love for boxing remained throughout his life.

By 2020, Reid had been living with often excruciating pain caused by the gunshot for more than twenty years. Every friend interviewed in this article mentioned the fact that, while he had bad days and better days and they could often see the depths of pain in Jan’s eyes, he never complained.

Novelist and screenwriter David Marion Wilkinson was another of Jan’s close friends. David and his wife live a few blocks from Jan’s home and spent a lot of time with Jan and Dorothy.

Jan and I were very close. We cared about each other. Jan had a lot of health challenges after the shooting. He had a weariness from his health, and from the bullet bouncing off his spine. He was partially paralyzed, but it didn’t stop him. I watched him struggle, but as much as I loved him, there wasn’t much I could do for him. And he didn’t want me to do anything beyond treat him like a man. That’s how you want to be treated. So what if he stumbled a little or fell? I let him fall and helped him back up. I took him to a funeral, and he couldn’t get up, so I just had to pull him to his feet. And the eye contact he made was like “did anybody see that?” Nobody saw it. . . .

Jan had been a very powerful person. And that kind of leaked out of him. He never lost his courage, never lost his fortitude, though. He was a fighter. I’ve seen him become militant about something he believed in. I’ve had to drive over to his house and say, “Don’t send another f’ing email, Jan. Not another one, okay? We’re all sick of it.” And he’d say, “I know,” but he was a fighter. And if you are going to be an artist in this world, you’d better have some of what Jan had. You’d better fight with toughness. You’d better realize that you’re going to be alone and nobody’s going to understand what you’re doing. Nobody. So, who are you going to explain it to? Jan knew that he could explain it to God. And that was it. Maybe Dorothy.65

One day in September of 2020, nine months after Dorothy died, Jan walked back into Richard Lord’s Boxing Gym, where his old friends still worked out regularly. Kip Stratton recalled, “Jan introduced me to Richard Lord, and we trained there together until Jan was shot. I’ve been training there for 23 or 24 years now. That day, Jan came in and set his cane down and climbed into the ring with Lord’s son, Tiger. He said, ‘I think I’m going to try and get in and do a little bit.’”

And he did. He got in the ring with Richard’s son and did a little light drill. And that’s when Jan had his first heart attack. Richard later said Jan had to sit on the apron for a while and he didn’t look good, but he insisted on driving home. He got home and knew something was wrong but went into denial about it. It got worse and worse and finally he called an ambulance. And it was one of those deals that had he called when he first noticed the symptoms, things might have turned out differently. But he waited too many hours while damage was being done to the heart muscle, and it could not be repaired. Richard, Tiger, and Richard’s wife, Lori, were inconsolable. Jan called me from the hospital twice and asked me to talk to Richard and Tiger and let them know that this was going to happen anyway. They had nothing to do with it. The doctors told him that he was going to have this heart attack. He could have been sitting home watching TV at the time. It was just time for it to happen. But it was so important to Jan that they know that nothing they did was responsible for this, but I know it was hard on Tiger for a long time.66

Lila Reid Vance said, “Even with all his health issues, Jan never had a heart problem. He was not even on cholesterol medicine. He called me from the hospital. He had waited three hours before calling EMS because he was afraid to go to the hospital during COVID. He was in the hospital for a while, and then he got to come home with this defibrillator vest. He was only home for about six hours. I had gone to my house to grab some things and during that time, he had another cardiac event. During the event, as they called it, somehow, he had gotten the vest off. We aren’t sure what happened. When I got back. he came to and was telling me not to call EMS. He said he didn’t want to go back to the hospital. I said, ‘Yeah, sure.’ But I was calling them. He just didn’t make it.”67

David Wilkinson said, “After Dorothy died, Jan was just sad. And then, with COVID and the extreme political division across the country, Jan was just tired. He had fought as long as he needed to fight. Jan was very intelligent. That's why he could walk in there and talk to Willie Nelson or Jerry Jeff Walker and turn around and talk to Muhammad Ali or Ken Norton, and then to Ann Richards or Barbara Jordan, and talk to them all on the equal terms. That's intelligence. I'm glad I got to sit there and just be around that. I'm really proud to say he was my friend. And I'm proud to say Jesse Sublett and Kip Stratton, Tom Zigal, Steve Davis, Eddie Wilson, and Chris Cook, all those Knuckleheads are my friends.”

Wilkinson attempted to describe The Knuckleheads. “We’re a small informal group of friends including those I mentioned and a few more. We get together to solve the world’s problems and celebrate friendship. Sublett gave us a name after one of the lunches, casually mentioning that he was playing somewhere in Austin and said, ‘If any of you old knuckleheads want to come out, it’s an early show.’ I don’t think anyone went to the show, but the name stuck.”

Wilkinson explained the dynamic that has held this group together for so long.

I love these guys. It’s just some friends who have lunch, ridiculously loose. There is not really a list, but you know when you are one. It’s just a bunch of writers, generally from small towns, who know what it feels like not to belong, to be a little different than what’s around us. They are alienated for whatever reason and academically smart. All published writers and they’ve all developed areas of expertise, Except probably for me. I never really got into an area of expertise, but it’s coming any day now. We recognize that we have a commonality. We are alike, and we are real friends. And we eat stuff we shouldn’t eat and say stuff we shouldn’t say, and I’ve had some of the most fun I have ever had with this bunch of guys. We celebrate when someone gets a new agent or finishes a book or gets a movie deal. And we are there for each other when things go bad. A couple have gone through divorces. Chris is overseas now and may never come back. Jesse just moved to LA. Eddie closed Threadgill’s. And Jan is gone.

I loved Jan. My life has not been the same without him. I think about him every day. I took him for granted, I know, but I really didn’t think he was ever going to go. He had survived so much. He was boxing when the heart attack hit. He was boxing. I talked to him in the hospital and said, “How old are you, man? 74? Really? And were you prepared to work the heavy bag? In retrospect maybe not.”68

Through his career and life, Reid remained a fan. Of sports and politics. Of music and of Texas.

“I’m not a music writer. I am not a political writer. I am not a sportswriter,” Reid said. As we ended one of our last visits, I asked how he would describe himself. We were sitting in his home-office in the hills of West Austin amid stacks of books and piles of paper, projects in various stages of completion. He leaned forward in his worn, wooden desk chair and fiddled with his cane, for a moment before saying, “I guess I’m just a writer.”69

Just a writer—who was improbably lucky.

Notes

1. Robert Earl Keen, interview by author, March 18, 2019.

2. Todd Snider, email correspondence with the author, February 24. 2022

3. W. K. “Kip” Stratton, foreword to The Improbable Rise of Redneck Rock by Jan Reid (Fort Worth: TCU Press, 2021).

4. Michael R. Levy, interview by author, February 28, 2022.

5. Jan Reid with Don Roth, “The Coming of Redneck Hip: Rock and Country Music Met in Austin: that friendship may make the state,” Texas Monthly, November, 1973

6. Dan Lindsey, interview by author, February 7, 2022.

7 Jan Reid, The Improbable Rise of Redneck Rock (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2004), 272.

8. Jan Reid, interview by author, February 17, 2019.

9. Reid, interview, December 4, 2012.

10. Jan Reid, “Postscript: The Improbable Rise of Redneck Rock,” Journal of Texas Folklore Society, January, 1975, Southwestern Writers Collection, Texas State University, San Marcos.

11. Reid, interview, December 4, 2012.

12. Eddie Wilson with Jesse Sublett, Armadillo World Headquarters: A Memoir (Austin: TSSI Publishing, 2017).

13. Bobby Earl Smith, interview by author, n.d.

14. Joe Nick Patoski, interview by author, February 24, 2022.

15. Smith, interview.

16. Jan Reid, Close Calls: Jan Reid’s Texas (College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 2000) 3.

17. Reid, Close Calls, 5.

18. Reid, interview, December 4, 2012.

19. Reid, Close Calls, 5.

20 Reid, interview, January 22, 2019.

21. Reid, Close Calls, 8.

22. Levy, interview, February 28, 2022.