JTMH Volume 22 | San Antonio's Garage Rock Scene

San Antonio's Garage Rock Scene, The Children, and Texas's Great Lost Psych Album

Bill Baird

Part 1: From Garage to Psych to Now: An Overview

From 1964 to 1968—the years between the Beatles' Ed Sullivan appearance and the psychedelic tidal wave that engulfed the music scene—San Antonio produced a clutch of timeless garage rock classics.

Short-lived bands including the Outcasts, the Stoics, the Chayns, the Five Canadians, Sweet Smoke, the Laughing Kind, the Argyles, and the Pandas issued a string of a propulsive, proto-punk singles that are both wildly unhinged and wonderfully addictive. To be sure, when record collectors voted on the 1,000 top US garage 45s for Mike Markesich’s book TeenBeat Mayhem!, San Antonio had five records in the top 30.1

“The best garage-rock records from the city have the same qualities . . . a willingness to experiment and cut loose, and a commitment to intense performances,” said Chris Bishop, who operates garagehangover.com, a massive online resource on the ’60s garage rock phenomenon. “For that short heyday of the garage sound, San Antonio deserves to be as legendary as any Texas city. San Antonio's music scene was more diverse, though, with many Hispanic artists, which may have made it harder to categorize.”2

Texas garage and psychedelic rock have long been prized among record collectors, and it continues to be a source of inspiration for a new generation of musicians. In recent years, the rock underground has percolated with acts exploring both garage and psych sounds. Its influence is apparent on bands as diverse as the Oh Sees, Black Lips, and Tame Impala, and it is the central draw of Austin’s massive Levitation festival.

“The word ‘intensity’ is synonymous with Texas music. And Texas has a reputation of being wild. Those two things together play a big part of Texas psych,” said Marc Smith, the artist behind current day psych-blues act Mockingbird Express, which operates out of the Alamo City. “San Antonio is unique in Texas because it's always been a crossroads city. And, as we know from Robert Johnson, crossroads are necessary for great music.”3

Indeed, that crossroads aspect of San Antonio proved crucial to its mid-sixties music scene. The city’s numerous military bases not only imported new people and ideas from around the country; they provided a crucial source of gigs for developing bands.

“It was an interesting situation because, well, there were actually places to play,” recalled Jim Ryan, bassist for legendary San Antonio garage rockers the Outcasts. “All the air bases around town had clubs—enlisted men’s club, officer’s club, teen club. Fort Sam had at least four places to play.

We'd be booked three, four, sometimes five nights a week at these military clubs.”4 That demand for live entertainment created a thriving atmosphere, with separate music scenes popping up across town.

Teen Fest

The West Side Sound, which blended R&B and Latin influences, for example, was largely captured by Abie Epstein and his studio at 735 North General McMullen. Dr. Epstein cut more than 900 45 rpm singles, many of which were recently compiled and reissued by Chicago's influential Numero Group label. While he is best remembered for his West Side soul releases, the studio owner also had an impact on the city's garage scene, recording many of its best singles, including releases by the Mind's Eye, the Argyles, and Robb London & the Rogues.

Epstein was a force of nature on the city’s Mexican American West Side, but the focus of the garage rock scene lay primarily on the city’s largely Anglo northern stretch. The undisputed impresario of that music scene was the visionary Sam Kinsey and his Teen Canteen. As record shop owner, Kinsey had his ear to the ground. Although a few years older than his patrons, he was among the first people locally to recognize an explosion of youth culture and organize events around it.

Among Kinsey’s noteworthy shindigs was the 1964 Teen Fest, which gave the Rolling Stones one of their first US shows. It was a disastrous affair. The opening act was a group of trained monkeys—yes, really—and the crowd in the largely empty Joe and Harry Freeman Coliseum booed the band offstage. Afterwards, a group of cowboys taunted guitarist Brian Jones for his long hair. Undaunted by the jeers, Jones walked up and crushed one of the rowdy’s Stetson over his eyes.

The Rolling Stones never forgot the gig. When they returned to San Antonio in 1974, Mick Jagger told Kinsey, whom he’d personally invited to the concert, “I wanted you to see we could draw a crowd.”5

That first Stones show might have been a disaster, but it inspired the bevvy of up-and-coming garage rockers who were in attendance. The Outcasts’ lead singer, Buddy Carson, was particularly taken with Jagger's strutting, which he incorporated into his band’s live performances after Kinsey opened his own venue, the Teen Canteen. The venue’s modular stage allowed bands to assemble the pieces in ways that catered to their own stage shows.6

“The Outcasts definitely designed the best stages,” remembered Bob Galindo, who performed in the Laughing Kind, the Zilches, and the Bourbons, and whose brother Dan Galindo played bass for legendary Austin psych rockers the 13th Floor Elevators. “It had a small runway for

Buddy Carson to do his Mick Jagger impersonations, which were excellent.”7

The Teen Canteen hosted innumerable shows for both new and established bands, quickly becoming a hot ticket for Alamo City residents hungry for rock and roll. Hundreds of teens regularly packed the performances, dancing for hours. “Imagine that! A place for young bands to play,” marveled Galindo in a program created for a 2010 Teen Canteen reunion.8

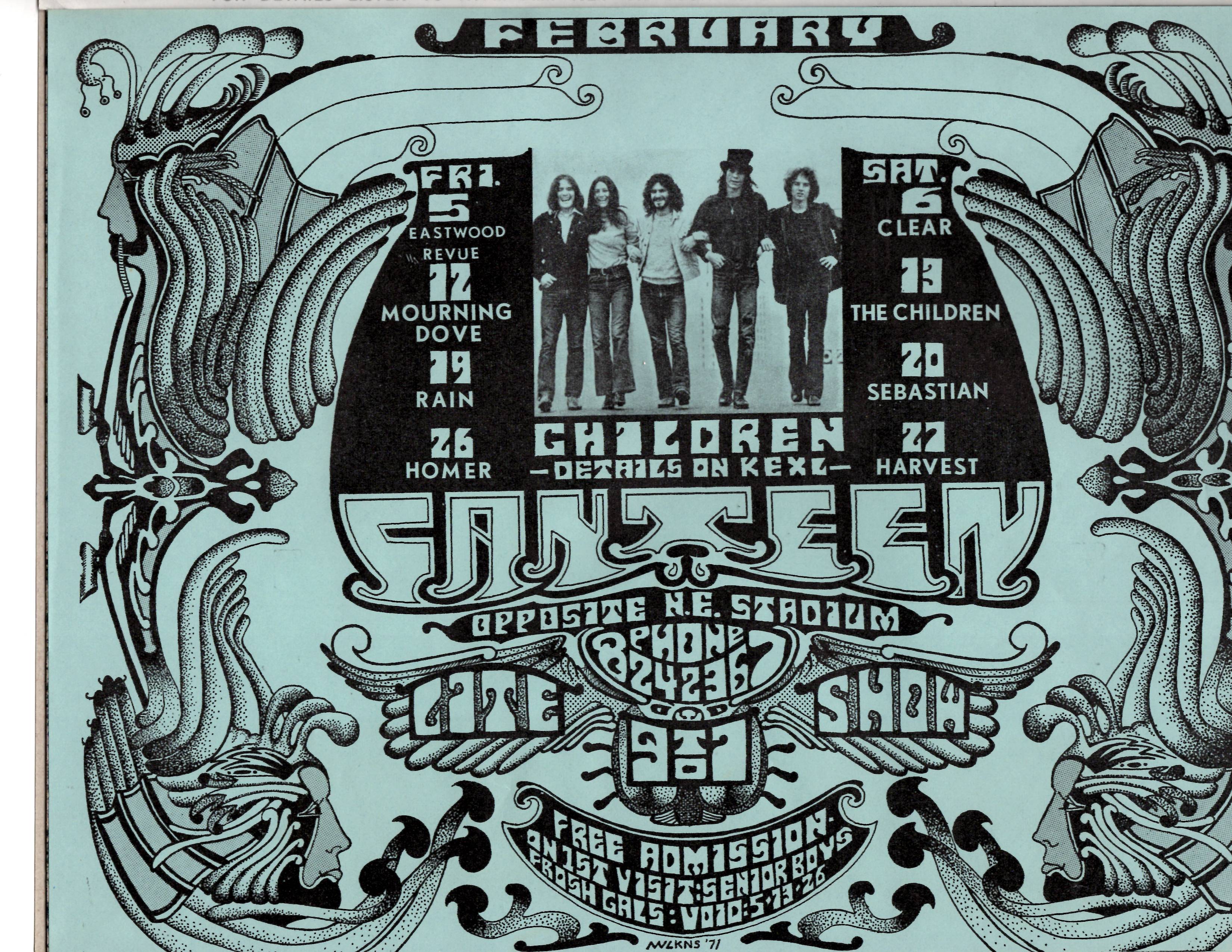

A Crucial Proving Ground—The Teen Canteen

The venue began at Jefferson Methodist Church Hall, then subsequently moved to Wonderland Mall, its most famous location, where it resided until 1968. After a bit more shuffling, it relocated across from Northeast Stadium, where it lasted until 1977. Kinsey envisioned the Teen Canteen as a safe, wholesome place for kids to enjoy music and create their own culture. It was also a place where parents felt safe leaving their teenagers. The space had a dress code and strict no-alcohol policy, and in its earliest days, drugs had not yet entered the picture.

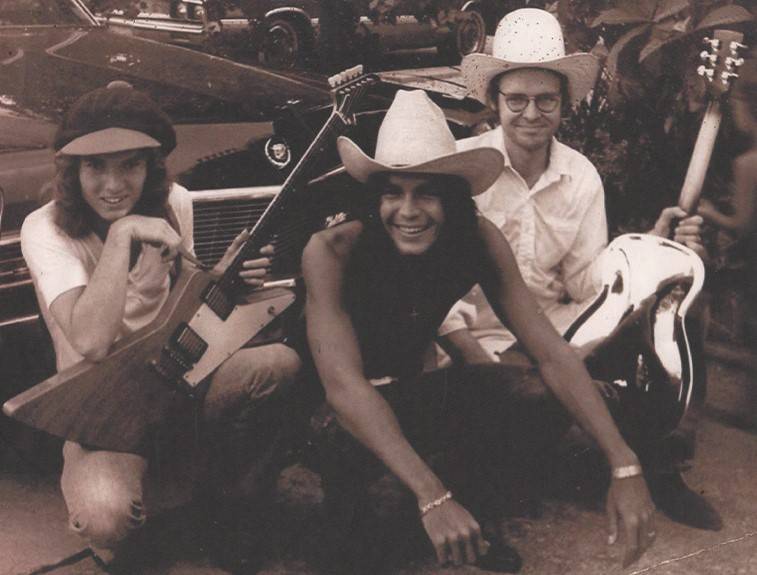

Photo 2: Sam Kinsey addressing the Teen Canteen crowd.

Courtesy of South Texas Popular Culture Center/TexPop/Michael Ann Coker.

“Sam Kinsey was different than most people. He had rules and decorum. Morality standards quite different than bars,” said Hector Saldaña, frontman of ’70s garage rock revivalists the Krayolas and Texas Music Curator for the Wittliff Collections at Texas State University, where Kinsey’s archives are held. “Kinsey gave these young people an outlet. It was an incubator.”9

To be sure, the Teen Canteen emerged as a crucial proving ground for prime regional talent. The venue gave ZZ Top its first paying gig—$150 on September 13, 1969—and booked Billy Gibbons’ pre-ZZ garage band the Moving Sidewalks. It also played host to a pre-Monkees Mike Nesmith and San Antonio’s legendary Sir Douglas Quintet, whom Bob Dylan once described as his favorite band. Augie Meyers’s Lord August & the Vision of Light played the Canteen’s grand re-opening at Wonderland in 1968.

Another of the Canteen’s early acts was Christopher Cross’s Flash. Cross later went on to stratospheric multi-platinum success as a ’70s and early ‘80s soft rocker. But early on, with Flash, the Alamo Heights High School graduate was known as a local guitar hero.

In Kinsey’s eyes, a healthy rock music scene actually was of great benefit to the community at large. “My main purpose of pursuing that business was to generate an income,” Kinsey said in a phone interview. “Later, I found it supported the local musicians. Finally, I found an unintended effect of the place was the positive effect it had on the attendees’ lives. It kept some people from dropping out of school because if they dropped out of school...they could not attend the Teen Canteen.”10

Documenting a Sound

But it was not just famous names that made up the fabric of San Antonio’s garage scene. The thriving environment birthed dozens of lesser-known bands that pushed and inspired each other. “It was fairly competitive, but we were all friends,” said Ryan, bassist for the Outcasts. “If somebody won the battle of the bands, that was fine, we just went on to different places, different dates, and different groups. It was a fairly thriving scene.” The Outcasts’ two singles, “I'm in Pittsburgh” and “1523 Blair,” are now among the most prized garage rock 45s of the era. “Last I checked, they were going for about $800 on eBay,” laughs Ryan.11

The band’s career began with gigs on military bases and slots on battles of the bands, culminating in a stint as Teen Canteen’s house band for more than a year. After opening for British invasion group Herman’s Hermits, the Outcasts hooked up with the two most influential music producers in Texas—the infamous Huey Meaux, who produced the Sir Douglas Quintet, the Big Bopper, and innumerable number one hits; and Leland Rogers, brother of country star Kenny Rogers and impresario of Houston's International Artists, perhaps the most legendary psych label of the ’60s. The Outcasts’ singles charted locally but stalled out around number 30. “We didn't have the payola to make it go,” Ryan said with a laugh.12

During those boom days, studios popped up to document the San Antonio sound, as did new clubs and psychedelic shops. Besides Epstein’s aforementioned studio on McMullen, Jeff Smith's Texas Sound Studios and Jim Ridgeway's Alamo Audio helped document the burgeoning scene. Alamo Audio also ran a label of the same name that custom pressed records in editions of 100 to 500 copies, perfect for local distribution.

The emerging clubs included the Mind's Eye on Austin Highway, the Love Street Light Circus on Commerce Street, the Mystic Moor on Austin Highway, Home on San Pedro, and the notoriously hip Pusi-Kat Club near La Villita. A Southside alternative to Kinsey’s venue, Teen Town, popped up in McCreless Plaza. Later, head shops and psych stores included the not-so-subtly-named Joint Effort and Granny's Teahouse also made an appearance.

Pre-Clear Channel Radio

Also contributing to the explosion was a radio landscape vastly different from today’s. Singles by San Antonio garage acts actually got play on major radio stations alongside records by nationally known artists. Long before Clear Channel and I Heart Media imposed playlist monotony, local DJs had autonomy and were able to take chances on local and regional bands.

Homer, a San Antonio garage group that rose from the ashes of the Outcasts, landed on the local charts by giving local DJs copious amounts of prime beef as enticement for spinning their records. Homer guitarist Galen Niles’s father, a supermarket manager, made the arrangements. Niles sprung from the garage scene to become the city’s reigning guitar hero for years, first with the Outcasts, the Pandas, and Homer, then forming Ultra, which played arguably the most famous gig in local history—the Sex Pistols’ legendary performance at Randy's Rodeo.

After 1967 brought the Summer of Love to San Francisco, a similar sound began to permeate the Alamo City’s music scene. Garage rock morphed into psychedelic rock.

Among the bands who underwent that evolution were the Stoics, a racially integrated band whose one single “Hate” is now considered a garage-rock classic. After splintering, members formed another group, the Argyles, who, after releasing some excellent singles, morphed yet again into the Mind's Eye. The latter group’s single “Help, I'm Lost”—a multi-layered affair featuring a violin plus a raga-esque guitar solo from Galen Niles—remains of one of the great lost singles of San Antonio music.

To accommodate the mind-expanding scene sprouting up around them, the Mind’s Eye even opened a club of the same name on Austin Highway, adjacent to the old Seven Oaks. It is now a parking lot. Band songwriter Steve Perron managed the venue while Charles Winans—the Sir Douglas Quintet’s first manager and arguably the city’s biggest “head” at the time—ran the lightshow. Old Heckle and Jeckle cartoons flickered on its inside walls.

“Really good vibe in that place. Very psychedelic,” Ryan of the Outcasts recalled. “We played there many times. It wasn't around that long, unfortunately.”13

Splintering Scene

The club’s overtly drug-influenced name made it a target for local law enforcement. After only a few months, the Mind’s Eye shuttered the venue and moved to LA, where Monkees frontman Davy Jones agreed to produce their debut record. He even repped the group on the famed Sunset Strip.

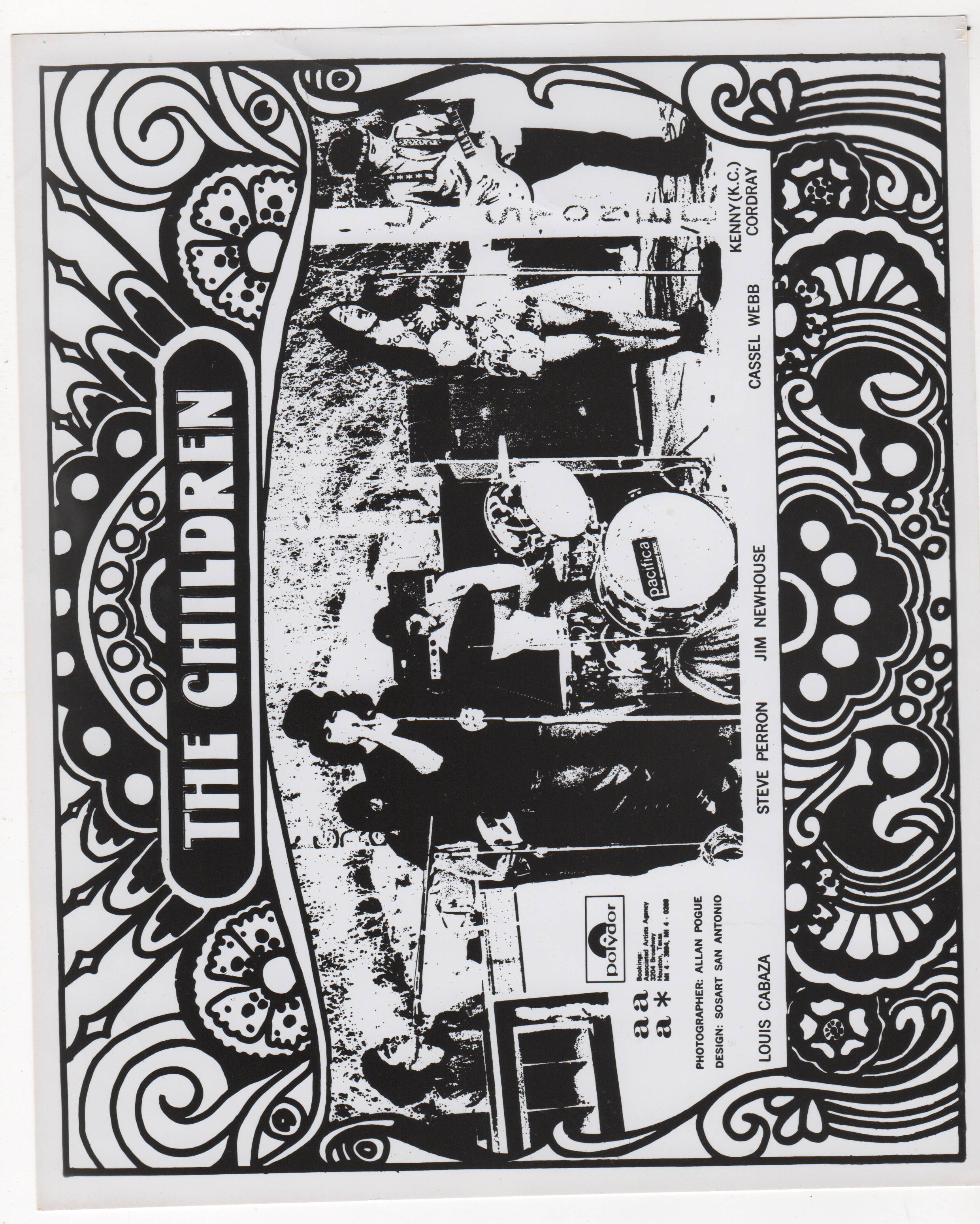

Amid money and drug problems, though, the group retreated to San Antonio, sans album, but with a new name: the Children. The Children's one album, Rebirth—recorded with International Artists’ Rogers at the controls—is now considered a classic of Texas psych. A second album, to be helmed by Lou Adler, the renowned producer behind Carole King’s Tapestry and other smashes, fizzled out amid more drug drags and money squabbles.

Just as groups disbanded, reformed, morphed, and fizzled, San Antonio’s scene itself was ever changing, and by 1968, it had started to dissipate. Looking for wider fame, some San Antonio bands preferred to go to Houston to record, while others, most notably Bubble Puppy, found success

in Austin.

By 1973, Texas also lowered its drinking age to 18, forcing the teen club scene to compete against regular bars. The Teen Canteen shortened its name to the Canteen. While it continued to provide a crucial proving ground for local talent, the initial magic had largely faded. “The marijuana scene came along, and I had to learn the scent, as the doorman,” Teen Canteen’s Kinsey recalled with a laugh. “Somebody would walk in and I'd say, ‘Oh, I like your cologne.’ They’d say, ‘Oh, I'm not wearing cologne.’ Then I'd sniff. ‘Oh, I swear I smelt some new cologne on you.’ And that was the cool way to let them know that I knew.”14

As harder drugs filtered through the scene, the innocence filtered out. Momentum stalled. The garage rock scene, almost as soon as it appeared, vanished. Not surprising, though. That ephemeral quality is intrinsic to youth culture. Kids grow up and scenes dissolve for numerous reasons—college, the draft, and addiction all played their part in this case.

“That's the culture of rock ’n’ roll. You get one shot,” said Ryan of the Outcasts.15

Digging Up Nuggets

The glorious rush of garage rock had passed. But it was ripe for rediscovery. As primitive early rock ’n’ roll gave way to the pomp and virtuosity of ’70s prog, something got lost. Namely, the fun. Early punks sifted through the remnants of the ’60s looking for inspiration. Most notably, future Patti Smith Group guitarist Lenny Kaye assembled Nuggets, a two-LP compilation celebrating overlooked rock 45s. It was the book of Genesis for the nascent punk movement, and its liner notes even contained one of the first written references to “punk rock.”

Eventually, Nuggets became a series of releases, then a box set, and other compilations surfaced, digging up obscure singles from the era.

“We got labelled punk in the ’70s, and it seemed to fit the bill,” the Outcasts’ Ryan said.16

By that point, rock culture was already mining its own past, finding inspiration in an earlier incarnation, whose unbridled energy now felt missing from the scene. The old became the new.

“Nuggets did what I always hoped it would do: spark this kind of archaeological interest, so all of a sudden, people started digging around for group garage band records. . . . So, it just kind of continues on and on and on,” Kaye told the website Musoscribe in 2019.17

That kind of rediscovery is ongoing, and it has continued to shine a light on San Antonio’s rich garage rock scene. Taken as a whole, the city’s output from the period is as good as anything on Nuggets, if not better. Alamo City garage 45s are some of the most highly prized—and highly priced—records on the collector market. The culture spawned by Nuggets has singled out San Antonio as singularly important, and numerous singles of the era popped up on subsequent compilations.

Enduring Influence

One of these compilations, Highs in the Mid-Sixties, was Mockingbird Express frontman Smith's first exposure to San Antonio’s first-wave garage and psych. Five volumes of that 23-record series were dedicated to Texas music alone.

“The sheer number of amazing Texas bands would surprise a lot of people,” Smith said. In 2022, San Antonio is still a crossroads city, and the vibrant feel of its early garage days continues to resonate.

“A lot of south Texas musicians feel a personal and spiritual connection with where it all came from,” Smith added. “There is an intensity, not just in how musicians play, but with how we consume music as well. There is a hunger here for rock and roll, particularly. It’s in the soil, the air, the water, and in people's blood around here.”18

The original wave of San Antonio garage rock, though short-lived, created compelling music that is now being rediscovered by another generation of local musicians. Even if those old records might be a little out of tune, that’s precisely the point. The songs brim with pure, unfiltered energy.

The recordings are still out there, breadcrumbs for those interested in learning the history of their own city and a fascinating era of rock ’n’ roll.

“They have this reckless abandon,” reflected Hector Saldaña. “It's almost like pure expression. There's no denying the creativity and the energy of these records.”19

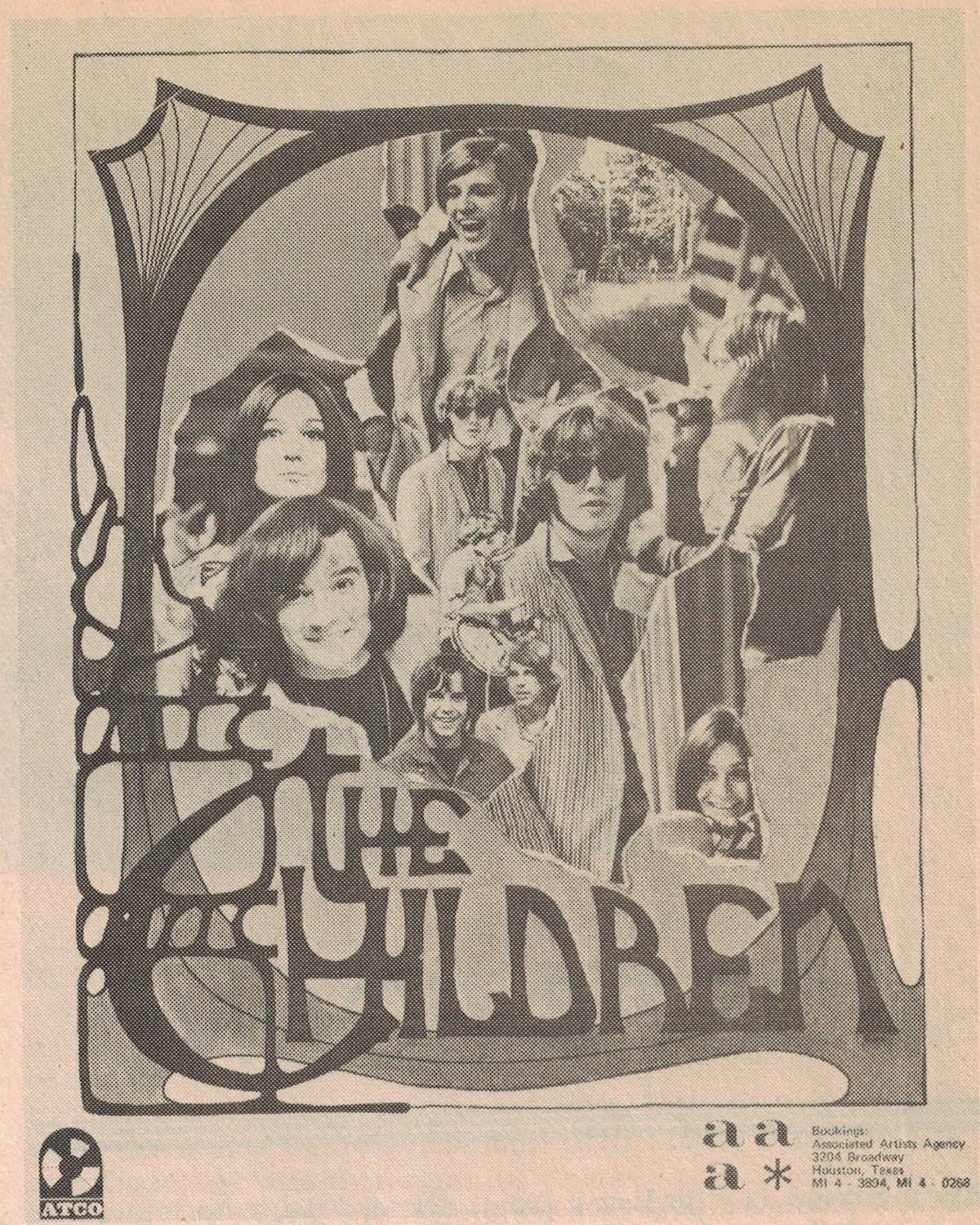

Part 2: The Children: A (Mostly) Oral History

Though the career of the San Antonio psych band the Children ended in tragedy, their story is an indispensable chapter in the untold, forgotten history of San Antonio music. During and after their short-lived stint, they stood at the intersection of some of the 20th century's most compelling artistic movements—garage, psych, punk, post-punk—and mingled and collaborated with some of its icons. They saw the 1967 riots on the Sunset Strip, Walt Andrus's Houston studio, the machinations of International Artists and Lelan Rogers, the Robert Altman film Brewster McCloud (shot in Houston), Hemisfair 68, Jimi Hendrix, legendary jazz composer Bill Russo, pop impresario Lou Adler, the Carpenters, Fluxus, new-music composer Phil Krumm, and much more.

The Children's individual members have fascinating trajectories as well, with Cassell Webb and Lou Cabaza foremost among San Antonio's great unsung musicians. After starting as a coffeeshop folk singer, Webb joined the Mind's Eye and the Children—straight into the intense, short-lived psych period. Her post-psych career is even more interesting, as producer of the Fall, Blondie, the Sir Douglas Quintet, and even Pavarotti. Cabaza, meanwhile, took several detours into piano bars and studio production before a stint in the Gap Band (“You Dropped the Bomb on Me, Baby”), and a long-term collaboration with Natalie Cole, including two performances at Carnegie Hall.

Meanwhile, the Children's frontman, Steve Perron, succumbed to drug problems early on and passed away, but not before penning the ZZ Top classic “Francine.” After the breakup of the Children, Rolling Stone ran a long feature on Steve Perron. The overall tone of the story feels more than a little tragic, however, right down to the title, “A Guitarist Who Almost Made It—Then Came Smack.” Over several pages of this issue (March 30, 1972), Steve described his relationship to drugs and the missed opportunities of his career. Perron died the following year.

Their legacy has long been forgotten, partially due to the band's tragic story, and partially due to San Antonio's neglect of its own rock and roll history. This is their story.

Early Years

Cassell Webb: I was born in San Antonio—brothers and sisters, six children. But moved around. I lived in England with my family. Music had come through the family and sometimes it comes through the ghost at the same time. I'd been singing in Missouri, where they'd asked me if I'd stay with classical voice—I have a very natural tone. And so I went, uh, no. I sang in a doo-wop band, started singing backup in, you know, local fun bands with my older sister and that kind of thing. And came back to Texas. I was a junior in high school when I got back—first time I'd been back in a while. I went to Edison. Around ‘65, ‘64. San Antonio was a hidden spot for music. It was so underground, it was beyond underground. Nobody knows that much about the scene in San Antonio.20

Lou Cabaza: I moved up from the Rio Grande Valley and my father was in the military, secret military. He got stationed in San Antonio in ‘64. I'd never been more ready to leave a place than the Rio Grande Valley. I finished high school at Cole High School on Fort Sam.21

Cassell Webb: SA is a military town—my father was a P-38 pilot and a colonel. They found out my brother and I were [Vietnam] protestors so I had to vanish because in the Air Force, if they found out your kids were protestors, there'd be problems—as a colonel, you'd lose a star, or lose your rank. I had to go and live in a friend's garage for a while. I didn't want to affect my father. He was livid, but he said “thank you.”

Lou Cabaza: San Antonio was different then. What a magical time. We used to do crazy stuff. I remember me and Mike Marochel (the Children bass player), he went up into the Tower of Life building downtown and somehow got to the top and climbed all the way up the antenna. We could see him up there, he was waving at us. When he came down, we asked him, “How was it?” “Windy,” he said.

Cassell Webb: I was really involved in the society of San Antonio. I was the runner-up for Miss San Antonio. Very few people know that. At that time, I was split. I mean, I was in a sorority. There's a few stories. . . . I put LSD in the sorority's food. Accidentally . . . accidentally. That was finally when I was ready to break loose. In that era of time, the only way you could move forward was to have that split personality. I did that. But not going crazy. Just . . . you were finally able to produce what you're seeing inside.

Miles Perron (Steve Perron's son): My dad died when I was six. His family, on the Perron side, they had a lot of oil money. He was running around acting like a broke musician, but he wasn't.22

Lou Cabaza: It was an amazing scene. But, for some reason, San Antonio is low on the totem pole in terms of recognition or realizing what they have. I don't know what it is. Perhaps a small-town mentality or something.

Garage Rock Scene

The San Antonio garage rock scene was one of the nation's most active, mostly due to the proliferation of teen clubs. Foremost amongst these was Sam Kinsey's Teen Canteen. A proliferation of young musicians, inspired by the Beatles, Rolling Stones, the Animals, and other “British Invasion” acts created a tidal wave of new bands.

Cassell Webb: Oh gosh, the SA teen clubs. The Teen Canteen. Well, I was mostly in the folk clubs, but in my teenage days, you went wherever you could go. Shows would happen anywhere. Like the first time I ever saw Doug Sahm. He played at my high school! Like a prom or something.

Lou Cabaza: I was in a group called the Impacts. From there, I met a guy named Steve Perron. Together, we were in the Argyles. He and I were just a really, really good team. We could just sit down and write together and it was just magic. I've never found anyone that I could write and collaborate so easily with.

The Argyles first gig was as house band at the Blue Note Lounge on San Pedro. Doug Sahm had just finished his stint there and we followed him. It was going well until there was a shooting on the dance floor and . . . well, that pretty much ended things there.

Miles Perron: I grew up on Argyle Street, right down the street from the Argyle Club (exclusive San Antonio social club). I'm pretty sure that's where Dad got the band name. Somewhere along the way, my mom became a groupie for my dad and one of his bands. And here I am.

Galen Niles: I was in the Outcasts and knew Steve Perron from those days. Him and Chris Holzhaus didn't get along all the time. I ended up playing on a couple of Steve's songs for the Argyles. “Still in Love with you Baby.”23

Cassell Webb: Lou and Steve Perron played the garage scene for years. They were such amazing characters together. The first place I met Steve Perron was at a drag race. I used to run cars, my older brother and I. My first drag race was there. I love cars—I still love cars. I have a drag racing trophy.

The Argyles, the Stoics, there was so many bands at that point. I was not involved in that. But I was in the Mind's Eye.

Lou Cabaza: We didn't like the name the Argyles. So we changed it. The Mind's Eye—pretty psychedelic. Everybody was doing psychedelics at the time. I remember me and Benny the bass player, we were going down to Laredo, he had some acid on him. He said, 'You got to try this.' So I took it. Ha. And I'd never even gotten high in my life. That was a car ride I'll never forget.

Phillip Krumm: There was this guy named Bill Ash. Incredible guitar player.24

David Ash: My brother Bill was in the Stoics and later the Children. In about '64, when the Beatles came out, Bill would've been in the sixth grade. He said, 'Dad, I need a guitar,' and he got an old Hofner. We moved to San Antonio about '65. I remember Bill immediately picking up a band and practicing in the garage, Al Acosta and those guys—they became the Stoics. Bill was fifteen when that got going. He looked older because he was tall.25

Chris Holzhaus: I was in the Argyles and went to Jefferson High where Mike, Al, and Sam went to school. When Max Range (the Laughing Kind) called Mike Marechal looking for a drummer, lead guitar, and bass, Mike called Sam and I, we tried out and got the job at the Dunes. After the summer was over and the Max gig, I returned to San Antonio. Steve Perron called me up . . . asked me to come back to the group now called the Mind’s Eye and record with them. . . . I was resurrected with Galen Niles for the Jox recording sessions. Later when Steve couldn’t talk Galen into joining the band, Bill came back as the rhythm guitar. . . . [Bill] was pissed at me for years. I told his mom to fuck off one time and he never got over it.26

David Ash: There was a dispute between Holzhaus and the rest of the guys. My brother Bill got recruited for the Mind's Eye and brought in Andy Szuch.

Lou Cabaza: Holzhaus was not the easiest guy to get along with, to play with.

Galen Niles: I recorded on the Mind's Eye single “Help, I'm Lost,” which came out on Jox, Abe Epstein's label. Cabaza wrote the music section and scored the cello parts. He was a music major over at SAC. I went over there and heard him just wail on the pipe organ they had. He was great.

He had a couple people from the San Antonio Symphony playing cellos. Had them in a little room. Me and Holzhaus, stuffed in a little closet, he was doing rhythm and I was doing all the lead work. The drummer isolated in a booth. And we recorded that all at once. Live. That was how they did it back then. 1-2-3-4, and you just hope for the best.

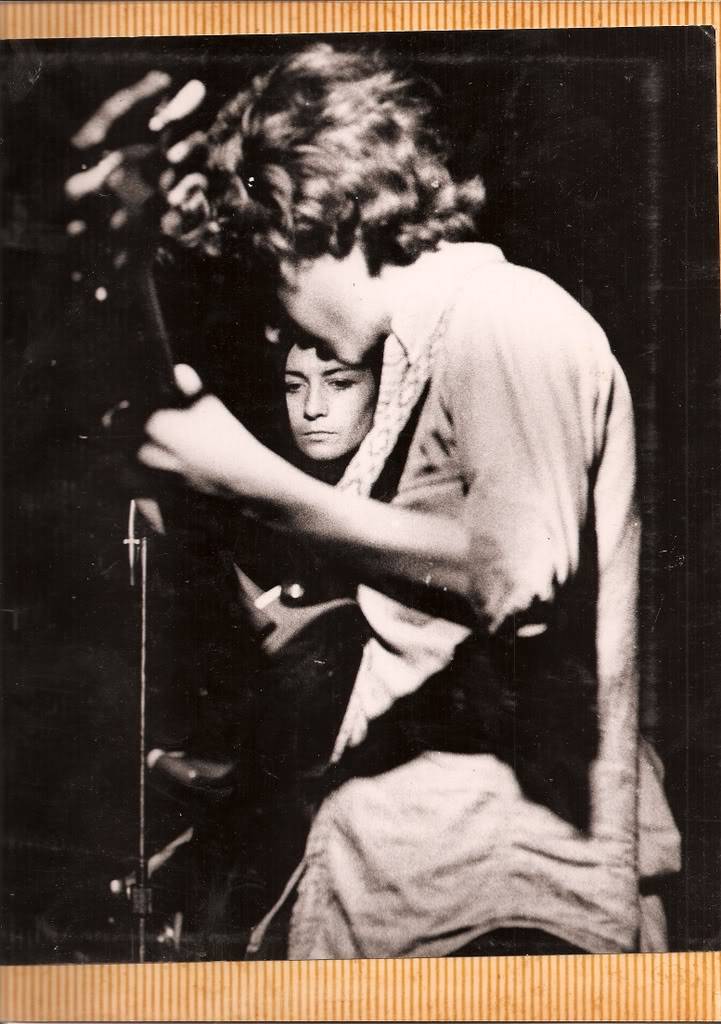

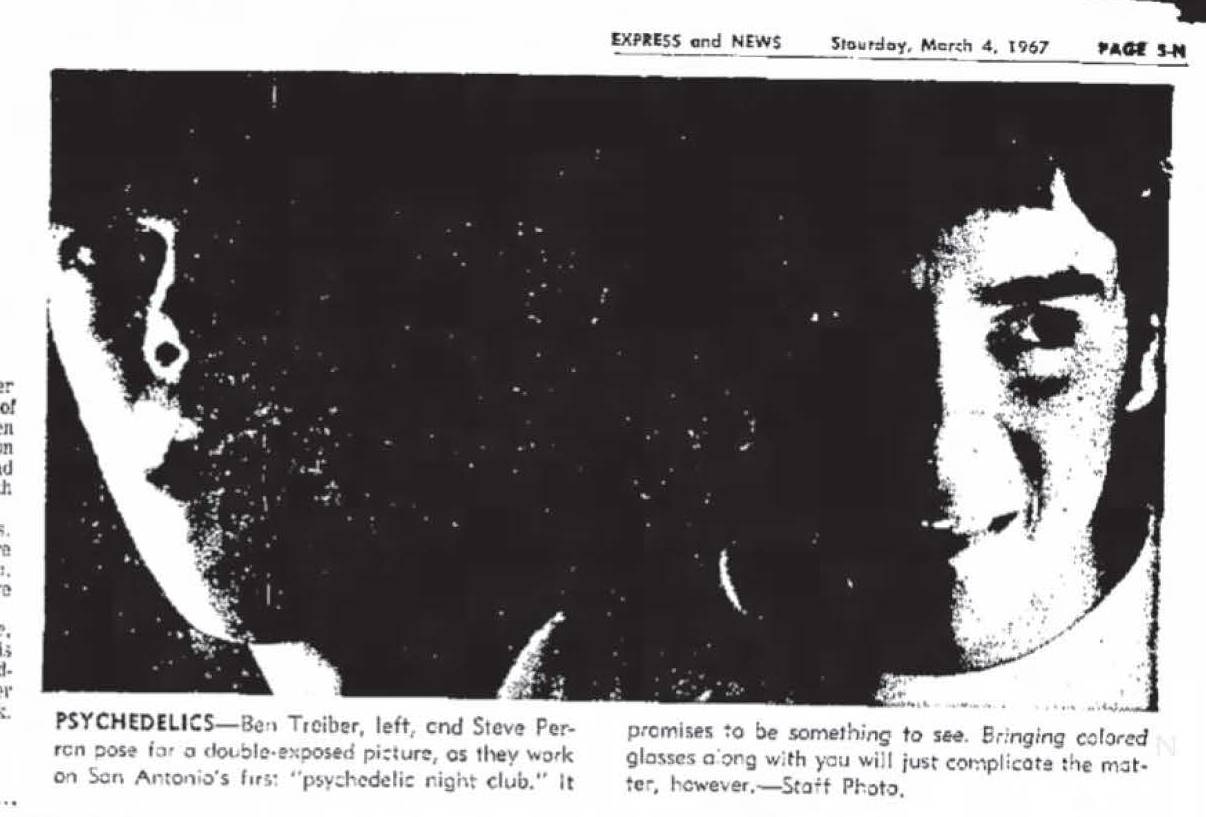

Lou Cabaza: Then Steve and Benny Treiber decided they wanted to make a psychedelic nightclub. That was also called the Mind's Eye.

The Mind's Eye Club

The Argyles turned into the Mind's Eye and, backed by family money, they opened a club of the same name, the first psychedelic club in the South, according to Perron. The club, located at 1234 Austin Highway, later became the Mystic Moor.

Cassell Webb: For the opening weekend of the Mind's Eye club, we played with the 13th Floor Elevators. It was amazing. Incredible energy and understanding for all the people involved. I don't know how they opened the Mind's Eye. I just don't know how they did it. But Steve was an innovator. He wanted to get out there.

Lou Cabaza: I remember being in the office one time. The Elevators were playing opening night. Roky Erikson comes to the side door and it was a little step up into the office and he missed that step, tripped, fell on the floor, and looked up at us from the floor and said . . . “Is this the Mind's Eye?” We had six or seven people doing oils against the walls. Pour oils on projectors and it makes all these colors. Everybody was loaded and, well, it was a blast.

Cassell Webb: There was a 30-foot tunnel to the club's entrance. You had to roll through it to get inside. And all of a sudden you're in there and the Elevators were playing. You could hardly see across the room from all the smoke. My parents would always drop me off at the Mind's Eye to play with the bands, ‘cause I was a teenager. They always knew I'd be singing, so they weren't bothered by the psychedelic aspect of the scene—I just never told them how you get in the back door, haha. I'd say, “Dad, I've got to go to clubs and sing with a band.” They were real nice and stayed outside, haha. ‘Cause it was very psychedelic.

Galen Niles: The Mind's Eye. Ben Treiber, the bass player in the Argyles, his grandfather had money. He bankrolled Treiber over there. We played there several times with the Outcasts. One time, Treiber gave us a check and it bounced. And my Dad took over. Said, “we're gonna sue you!” Treiber's grandfather wrote us another check to make that good.

David Ash: Our parents were very supportive of Bill actually. My folks were kind of cool in that sense. My dad was deeply entrenched in the big bands in his era, the swing era. So our family was into music. They actually went to the Mind's Eye! They wanted to see him there. They always supported him, supported him when he went to California at sixteen. When the Beatles' Lonely Hearts Club Band album came out, Bill made a point of playing it to them. He told them, “Turn your minds on, sit down, and listen.” And they did. It was that kind of scene.

Lou Cabaza: The club lasted a very short time. The police just couldn't handle it. We got shut down, so after that, that was about the same time we went out to California.

Out to LA for the First Time

The Children attracted the attention of Mike Nesmith, who was smitten with their new single, “Help, I'm Lost.” In 1967, the Monkees sold more records than any other group—more than the Beatles. Having a Monkee in their corner meant doors would open. Thus began the Children's first trip to LA, during the 1967 summer of love.

Cassell Webb: I'd been playing with Mike Nesmith in San Antonio folk clubs. I met him there. Steve Perron's family and Mike's family were very close friends. They kind of communicated all together. And Benny Treiber was friends with Mike Nesmith's sister. That was how the communication line opened. Nesmith went everywhere to support the Children. He wanted to work with us, but he was just too busy. He introduced us to Davy Jones, who wanted a record company. It was Laramie records.

Chris Holzhaus: My girlfriend (and later my wife of 23 years) at the time went to John Marshall High with Mike Nesmith’s cousin Adria Adair. Mike Nesmith came into San Antonio to visit the Adair family and Adria called my girlfriend. I went with her over to the Adair’s with the 45 we cut of “Help I’m Lost” for Jox in hand. Mike called Davy on the spot and told him I have a new act for your label. He invited me to his place in Hollywood and I took Ben Treiber with me (his grandfather loaned us two credit cards to make the trip since I was broke). We got a deal with Davy, went back to Texas, packed the band, and returned.

Lou Cabaza: Our first break. We went out to California, pulling a trailer in an old ‘59 T-bird. Davy Jones was gonna be our producer. He was in the studio while we were recording. It was the summer of love. We were walking everywhere.

Cassell Webb: We played the whole Sunset Boulevard. On Sunset there were all the psychedelic bands. It was the beginning of all that. That's when they burned down Pandora's Box. We played The Hullabaloo, the Whisky a Go Go, with the Seeds, Spirit. We did all that kind of work, like everyone else. We all shared a little hotel room where we'd sit and rehearse. We'd already done a lot of that in Texas though—we were ready. The guys were fabulous to me. I was their little sister. Watched over to the point that I had to say, “Please, go somewhere else and let me go out.”

Chris Holzhaus: When we started to record, Ben couldn’t cut it and Davy told us to fire him. That’s when I called Mike Marechal in to replace Ben. Bill wouldn’t call Mike because he knew Mike had a problem with him from the Stoics days (they hardly spoke during this time). After the sessions at Gold Star Studios, Hollywood, Davy was patting us on the back stating, you people are going to be stars! He left on tour (with Jimi Hendrix opening) and we sat around for two months waiting for our record to come out.

Lou Cabaza: Things were changing. It was at that time that our producer, the guy producing us through Davy, he thought we should change our name. So our name changed to the Children. Our bass player—we let him go because he wasn't very good. Another bass player flew out to join us in our catastrophe. But hey, we were in California.

Cassell Webb: That was all going fairly well. Then all of Davy's world fell apart. Jones's manager stole the money, basically. The band was sleeping in his garage. Steve had other places, shall we say. We didn't have any money at all.

Chris Holzhaus: Davy’s manager screwed him/us out of a future. Embezzled all the running capital while Davy was on tour.

Lou Cabaza: I think Davy's management company, it was the mafia, the mob. They never broke our arms but they did strong arm us into signing contracts. We were just kids. “You're gonna sign this now!” they said. We had to sign a letter to get our disabilities removed.

David Ash: Bill went on the first trip out there to California. He was sixteen! He told me, “We did great out there on the Sunset Strip, but the managers were making all the money—taking advantage of us. Had we had better managers . . .”

Lou Cabaza: We were living out in the streets for about a month or so. Two or three of us were staying in a garage with just a mattress on the floor. Basically, we did the homeless thing, but we were young, it was cool, and we were in California. Until we got really hungry. And we did. I remember going over to Laurel Canyon to this church just to get a peanut butter and jelly sandwich.

Cassell Webb: And so we were forced to leave and come back to Texas.

Retreating Back to Texas / Hemisfair '68

After the deal with Davy Jones's Laramie Records dissolved, the band returned to Texas to regroup. At this time, the group connected with Philip Krumm, a slightly older avant-garde composer who had performed with John Cage, Yoko Ono, and the ONCE group, and studied under Karlheinz Stockhausen. Krumm became their manager.

The city of San Antonio was undergoing major changes as well. With a sweeping and controversial use of eminent domain, San Antonio had razed the entire Germantown neighborhood near downtown to make way for Hemisfair 68—the world's fair intended to showcase SA as a major modern city.

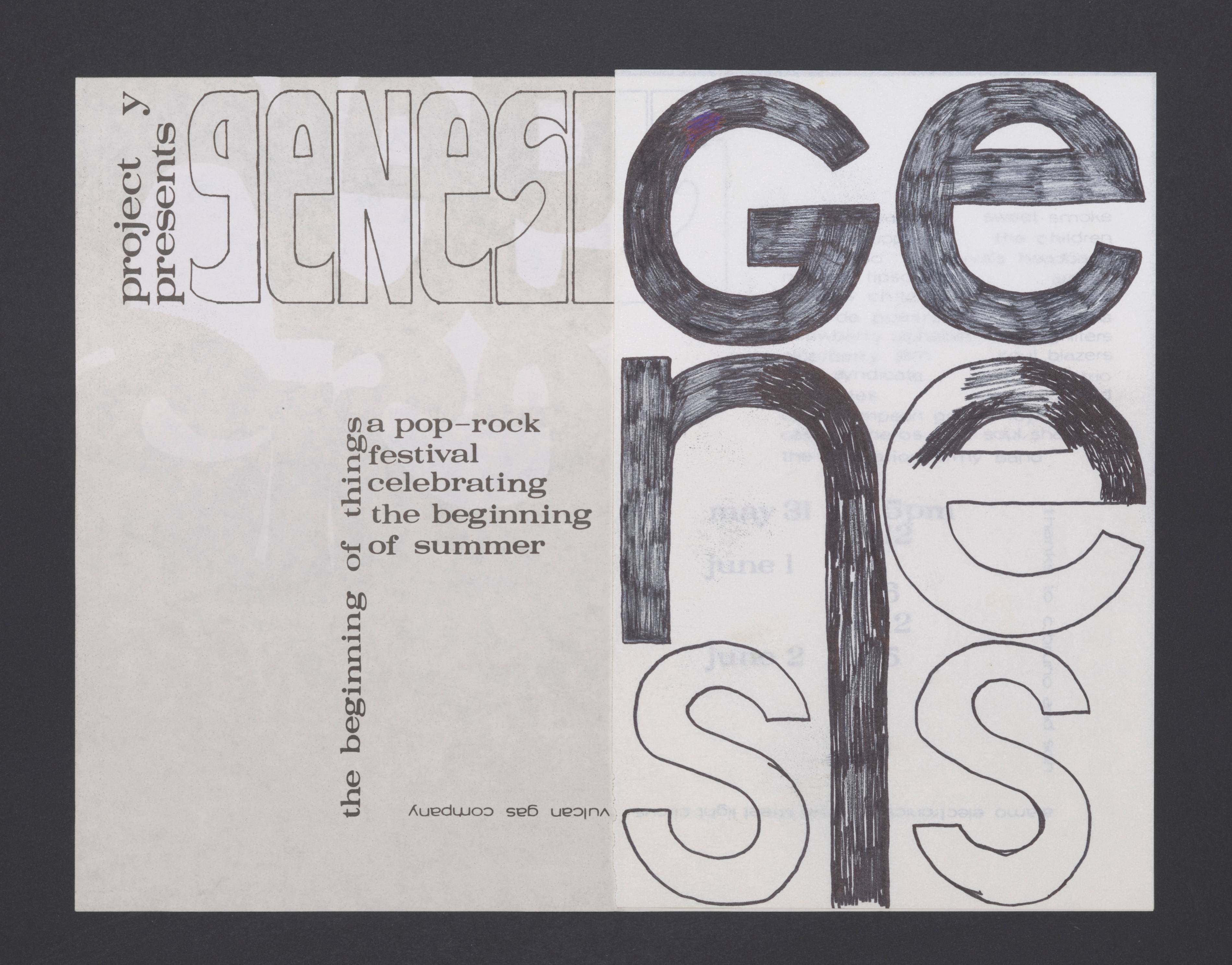

Hemisfair, laid out in numerous building and pavilions, included the “Youth Pavilion” (known mostly as Project Y). Project Y was an ambitious attempt to bring music and theater to Hemisfair, and kicked off with the Genesis Festival, the “1st pop-rock festival in the Southwest,” according to promotional materials. The festival's technical directors, led by Gregor Gregg, arrived at the Genesis Fest from Monterey Pop, where they'd put together an iconic success. Philip Krumm, the Children's manager, ended up in charge of Project Y's music and light show.

Lou Cabaza: Philip Krumm! Phil is a genius, a real genius. You could almost hear him thinking. I always thought if there were people from outer space—travelers, it'd be him.

Cassell Webb: The first time I met Allen Ginsberg was in San Antonio at the Bug House (Phil Krumm's apartment). That's where I met Ginsberg and Bill Burroughs—when they were coming through to have a good time in Mexico. At that time, I thought they were ancient but . . . they weren't.

Lou Cabaza: The bug house! Oh man. Phil Krumm lived above a pesticide company, ABC. He lived off Blanco before they put the I-10 in. I was going to San Antonio College at the time—we always ended up at Phil Krumm's. It's where we went to get high. He was our manager for a while. A manager for a longhaired band in the ‘60s. It had to be pretty tough.

Phil Krumm: I managed a couple of really good bands: the Children and Rachel's Children. They were already named when I found them. Haha. Manager in quotation marks. Haha. I didn't know what I was doing but they tolerated me. I had been studying with Stockhausen at UC Davis around 1966. Ended up coming back to take care of my family. And I got the opportunity to be assistant to the director of the youth pavilion. Director was a nice guy, but he was in and out. So I de facto got to run the youth pavilion.

My San Antonio lighting company was based on performances I'd done in Ann Arbor with the ONCE group. See, in Ann Arbor was a guy named Milton Cohen. He had created the Ann Arbor Space Theater. It was the earliest of the light show kind of things. Not the traditional type with overhead projectors but a large turntable with bits of mirror, magnifiers, different kind of reflective glass. And around the turntable were various projectors, regular projectors, slide projectors. And what Milton would do (and we all contributed music)—he had this big studio, with scrims and screens everywhere. He would shoot these projectors into this mirror magnifying glass turntable creation and—poof—this splay of stuff all around you all the time. All flickering around in space and moving through these scrims.

So I was invited back to San Antonio and basically ended up in charge of Project Y. I had my own light show called Light Sound Development—LSD. Haha. Charlie Winans and I built a light machine like Milton Cohen's. Charlie was really one of the great San Antonio artists. I was sorry when he died—he was one of the terrific people.

Anyway, the Youth Pavilion was mainly for rock bands and stuff. I organized the music and did lights with my lighting company, LSD. We did a show with Rachel's Children and I don't know why exactly, but it was one of those times when everything takes off where the music takes off and goes off on its own. The light show was fantastic. Charlie Winans used to say that. “Every once in a while you do something and you don't know how.” That's what that was. Everybody did something they didn't know how. It was one of the most wonderful concert sets I ever went through.

David Ash: I was at that show at Hemisfair, the Youth Pavilion. It was pretty amazing.

13th Floor Elevators Break Up at Hemisfair

The 13th Floor Elevators, Texas's most celebrated band of the psychedelic era, also intended to participate in Hemisfair, but the band broke up before ever playing the gig. Hemisfair ended up hosting the Elevators' breakup. Philip Krumm played an unwitting role.

Phil Krumm: I met the 13th Floor Elevators early on, right when their first 45 of "Tried to Hide" and "You're Gonna Miss Me" came out, about 1964. They were all very smart and interesting people and I kept in touch, aperiodically, until the very end, which I happened to be around to see, even be part of. Roky had gotten to be pretty far out by 1968—a very important year for many of us—because of all the acid, etc., that he'd consumed . . . Across the street from HemisFair was a rock bar which had a sister venue in Houston (Love Street Light Circus). The manager was—at first—a rude and obnoxious fellow who treated all musicians like cat litter, felt they needed to be kept in their place. The Elevators were scheduled to play there on a Saturday night, but no one mentioned that to me. Roky'd made friends with a wonderful Vietnam vet named Charlie Powell, who was heavily—as we said at the time—shell-shocked, now under the blanket PTSD. They were both too damaged to communicate effectively with most of us, but got along excellently with one another. I had a Cadillac hearse at the time that I'd bought while in California in 1966. Charlie and Roky showed up and asked if they could borrow it to go to Austin. I said “Of Course” and off they went.

Only minutes later Tommy Hall showed up looking for Roky. They were scheduled to perform at the rock club and the manager was already in a bad mood and now Roky was obliviously headed for Austin in my hearse. Tommy said, "without Roky, we're screwed." I went with Tommy to the rock bar and watched him endure the indignities of the hot-headed and verbally abusive manager, happy to chew out and insult the most rugged and extraordinary rock group Texas ever produced. I had an occasion to see him later in the year. He said he felt badly about how he dealt with them but his experience dealing with bands over the years made him see them as mostly stupid cattle.

That was the end of their concert work together. I heard about an Elevators gig happening in Ingram a year or more later at the Old Dog Saloon but when I got there it was just Roky and his friends, no Elevators at all. I politely indicated that this was bad form and he shouldn't pretend to be the Elevators. I think he already knew this and I just reinforced it a bit. He never did that again. I should say also that no matter how zonked out he was, or how straight, he always remembered me and my name, which was always wonderful and surprising to me.

Actually, the Elevator who kept in touch with me the longest and spent the most time talking to me about them and their experiences was Stacy Sutherland. He was very smart and literate and had a great way of parsing out the history they'd all passed through during the turbulent sixties. He was responsible for the final album Bull of the Woods getting out at all; he did most of the production work on it and wrote much of the material. He'd promised that he'd bring me a lyric sheet for it since some of the words are hard to make out but—as many people had feared might happen—his wife shot and killed him before he could make that visit. It was a sad and stupid loss of a nice guy and good friend. He's buried at Center Point.27

Bill Russo and “Civil War: A Rock Cantata”

Bill Russo, having previously served as Stan Kenton's arranger and creator of the London Jazz Orchestra, was a formidable American composer forging new creative pathways. Inspired by the rock scene, Russo had begun experimenting with writing scores for rock bands.

At Hemisfair, Bill Russo debuted a new piece entitled “Civil War: A Rock Cantata.” The subject matter took on additional resonance as Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated three days prior to its debut. All over the US, riots were breaking out; 1968 felt like a year in which the country could split apart. Against this backdrop of intense civil unrest, Russo debuted his piece. For its Hemisfair performance, the Children were hired to be the performers, with Cabaza providing some of the arrangements. The Children later used some of the compositions from “Civil War” on their debut record, the classic Rebirth.

Don Gardner, music critic for the San Antonio Light newspaper, wrote, “Bill Russo's ‘Civil War Rock Cantata’ was the most exciting single musical event I've ever witnessed.”28

Phil Krumm: I was instrumental in bringing Bill Russo. Hemisfair commissioned his piece “Civil War: A Rock Cantata.” The Children used some of the songs on that record. They recorded those without asking him. They thought it'd be ok. Probably wasn't the right thing to do, but they were kids! And it didn't hurt anybody and got his stuff in front of new people, in front of a whole new crowd. At least it got his stuff to people who never would have heard of him. So I think it was probably okay.

Lou Cabaza: We used a couple of Russo's songs on the album. Well, actually they were poems but we rearranged them. Russo gave us the idea to use strings on Rebirth because we had strings going for his rock opera. Russo's rock opera wasn't very long and it was kind of an experiment with dialogue. It wasn't so much an opera, but like coffeeshop poetry, taking it a step further with more of a production. We were the band that did it. And that opened up some doors for us in Houston. Lelan Rogers had come to hear us. We'd started to get a reputation around town, even from our disastrous Monkees California trip.

The Characters of the Houston Psych Scene

Hemisfair provided a much-needed boost for the Children as thousands poured through the site to sample the World's Fair's offerings. Among those who witnessed the Children's acclaimed performance of “Civil War” was Lelan Rogers, brother to Kenny Rogers, and producer at Houston's famed International Artists records, home to such luminaries as Fever Tree, the 13th Floor Elevators, and the Red Crayola. With a production offer from Rogers, the band moved to Houston, which at the time hosted an exploding psychedelic music scene.

Cassell Webb: The band was falling apart, and then Lelan Rogers arrived. A unique character. Cinema Records and Rebirth happened because of Lelan. He did International Artists and all the psychedelic bands, but we were mostly in Andrus's studios. You'd go from Goldstar and cross over and go to Walter's. I lived behind the studio.

Lou Cabaza: Walter Andrus was amazingly smart and incredibly talented. He put his honest knowledge engineering in his studio. He had a one-inch eight track we did the album on, a Scully. He was the first guy I'd met who could hear things that nobody else could hear. A genius. When he was a little boy, he jammed up the Houston shipping channel and stopped all the ships, doing a radio broadcast.

He flew a plane that looked like Amelia Earhart's plane. He'd take these long flights with no flight plan. . . . He just followed the highway.

Cassell Webb: The folks at Andrus's studio taught me about microphones. It was one of the only places in Houston where I had a place to stay and learn about music. Frank Davis was the first one to really show me how things worked. Frank and I did music together for years afterwards—all kinds of different music in Texas coming forward.

But I always loved the studio. The first studio I ever went in was Buddy Holly's studio in Clovis, New Mexico. My older sister took me there. He was cool. It was still operational at that time. Buddy was in there.

Johndavid Bartlett: I got to know the Children when we were all hanging around Love Street Light Circus and Feel Good Machine. Love Street was the third floor of an old seafood warehouse down on Buffalo Bayou—Alan's Landing—turned into a psychedelic club. (ed. Note: Love Street also opened a San Antonio branch, directly across from Hemisfair. The SA branch was the site of the last 13th Floor Elevators gig.) They had a light show called Jelly Walls Eye Pack. It's where the Elevators played, and others—Shiva's Headband, Jefferson Airplane. There were no tables and chairs—the whole floor was covered with pillows and there were little eighteen-inch-high shelf tables on rugs between the rows. And everybody laid down on the floor or stood around the edge of the room.29

Cassell Webb: It was an amazing time. So many people. Janis Joplin and I were friends. I was four years younger. She and I had the same boyfriend at one point. We sat on the same porch, is that a good way to put it? “Hey darlin, what are you doing here?” “Hey darlin, what are you doing here?” She and I met again at one of her last concerts in Houston. Another time, Billy Gibbons and Lightnin’ Hopkins and I sat on a porch and I watched them play together. I never thought I would be sitting on that porch. Listening to true folk music. That's always been my favorite type of music—I started out that way. And Guy Clark was part of the whole Houston scene. Guy was pretty psychedelic at that point. He took photographs of me and the bands and was brilliant. He hadn't even thought about music yet. Mayo Thompson was there too. We did Saddlesore.30 He was always a very avant-garde artist. I still have a Christmas card from him. Someone dressed as Santa Claus, feet up on the train seat, just saying, “Ho. Mayo.”

Johndavid Bartlett: International Artists had a house over in Galveston—that's the famous one where the Elevators stayed. They had another one a couple of blocks from Goldstar Studio. Some of us would stay there when we were in Houston. Lou Cabaza, Steve Perron, and I were staying at the house. International Artists had brought the Nazz—Todd Rundgren's group—to the Love Street Light Circus and, suddenly, the Nazz's label cut them off—credit cards cancelled—and they were stranded in Houston. So they came and stayed at the house a couple weeks. We had to move out. When they split, they left so quick they forgot some stuff. Todd Rundgren left his leather jacket in the closet and Steve Perron put it on and was like, woah! And he wore it all the time after that. Steve in Todd Rundgren's jacket.

Rebirth/ATCO

Over the course of several months, the Children recorded their classic debut LP, Rebirth, which would later find a home at ATCO, a subsidiary of Atlantic Records.

Lou Cabaza: Rebirth wasn't simple garage rock and that was probably my influence. I didn't want to play three chord songs. Steve would come to me with an idea and I'd stretch it out a bit more. I put more of a classical influence in there, orchestrated some strings on the album using ten or eleven string players. They came in and saw my long hair and gave me the cold shoulder—at the time, that was shocking. So I passed out the charts. Next thing you know, they're woodshedding. We all ended up friends because they liked the music.

Cassell Webb: Dub Weathersby did the Rebirth album cover—it's brilliant. Beyond psychedelia. I never expected there'd be a woman on the cover looking out over a valley . . . and that's exactly what it looks like where I am right now. I'm always reminded of it when I come back to England. It's like, where in the world did this cover come from? Dub is still an artist. Somehow he came up with all this.

Dub Weathersby: Phil [Krumm] asked me if I would be interested in designing an album cover. I had been working in the art department of a local TV station and was happy to have some work. All I knew about the group was the name of their album, Rebirth. I worked on the design probably for a couple of weeks. Influences for the art came from the art and music of the time, along with LSD.31

Lou Cabaza: It was fun times. We were always broke. We lived in back of the studio in this old house that Walt Andrus owned. And it had cockroaches the size of rats. We used to have to spray the bedposts so they wouldn't crawl on us in bed. We heard 'em in the walls. But what did we care? We were young! We'd do anything to make it.

Dub Weathersby: Most of the Rebirth album had been recorded by the time I was hanging out in the studio. I did get to talk, make noise, and contribute to the ending of the song "I Got Involved.”

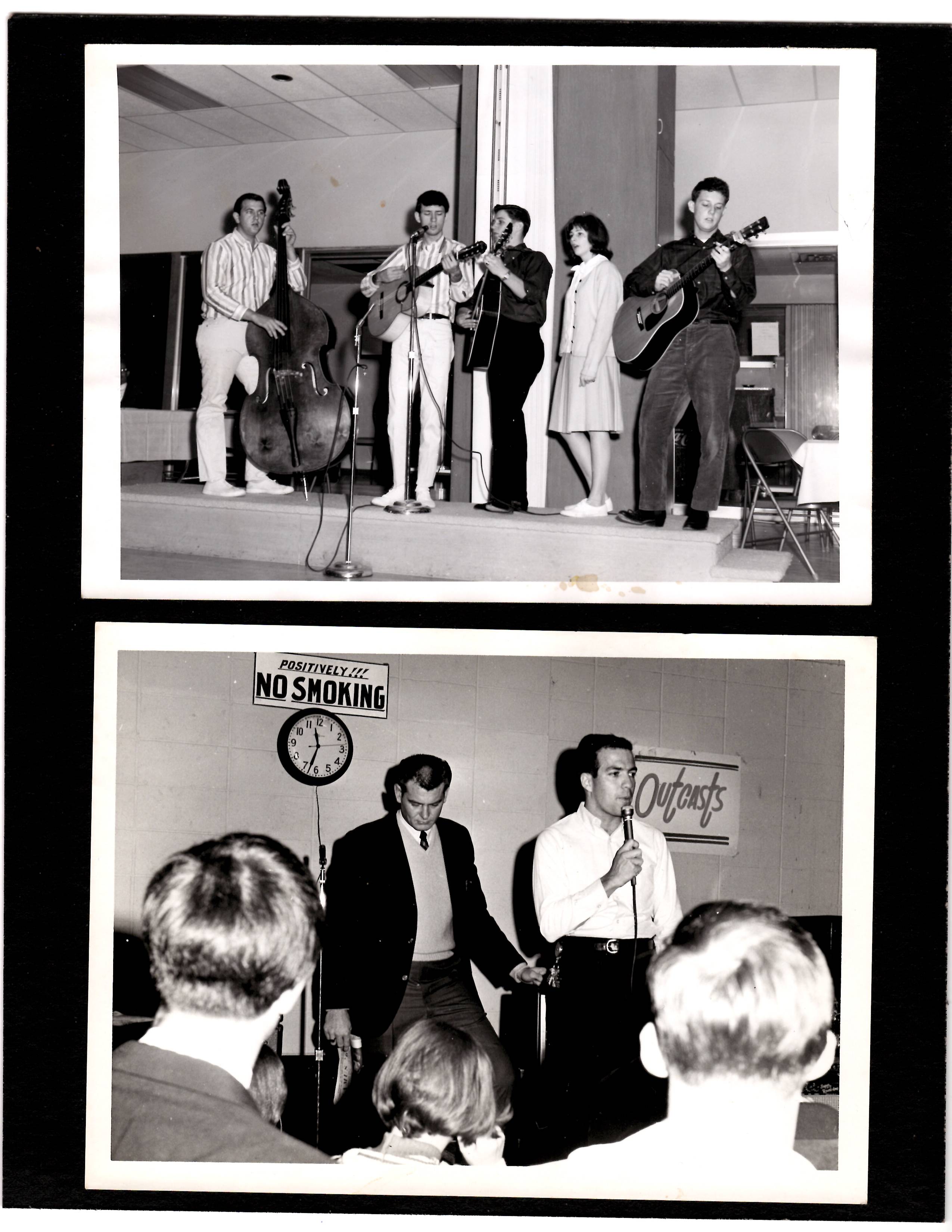

Courtesy of Sam Kinsey Teen Canteen Collection in the

Wittliff Collections, Texas State University.

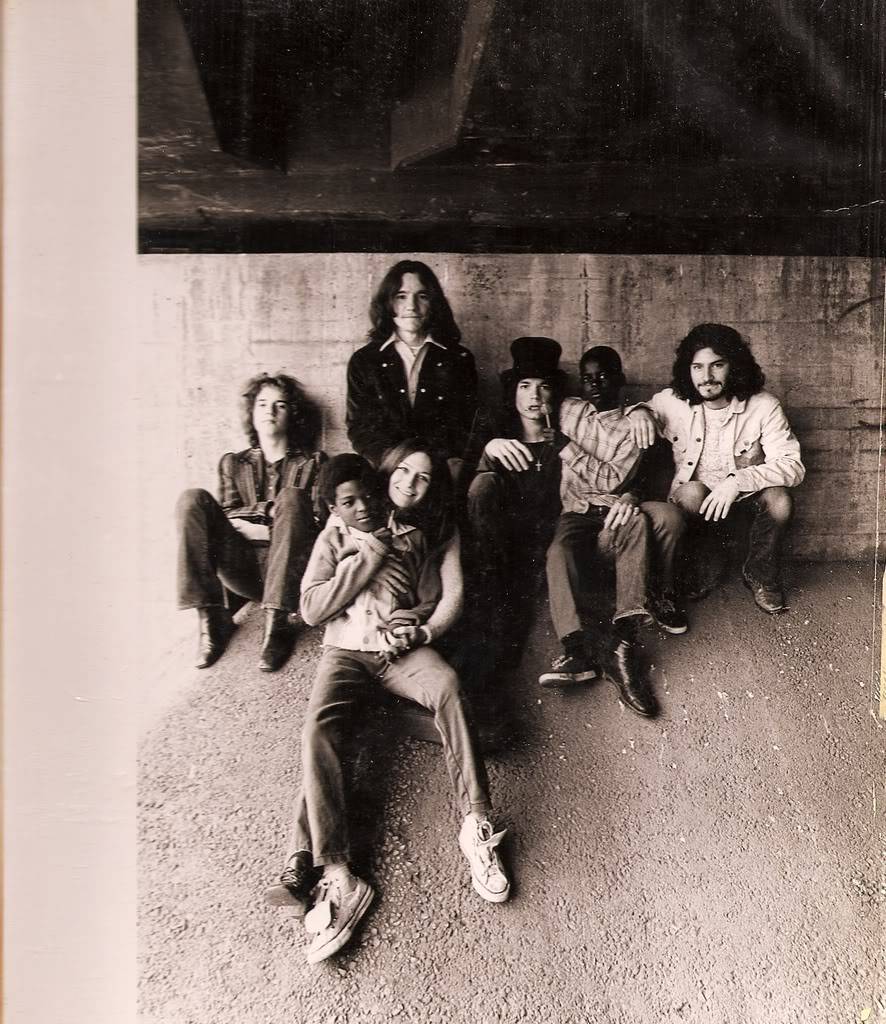

Lou Cabaza: We spent two or three months on that album. It set a high bar for me, going forward. Bill Ash played most of the guitar stuff on there. He was great but maybe not for us. We wound up replacing him with Kenny Cordray.

Hardcore Texas

Living in Texas at the time was difficult for the Children and all fledgling hippies. Traditional Texas culture didn't take too kindly to long hair and liberated women.

Cassell Webb: I never knew too many girls in San Antonio in bands. It was very unusual. I hung out with a lot of boys because of my brothers—being in the military, you take your time, meet people everywhere, you have to just to survive. But it was difficult to be taken seriously. “Wow, you have a female singer. . . . What does she do?” Being the girl in the band in the ‘60s wasn't a strong position to be in. I was writing songs and I wanted the Children to play them and they were like (dismissively) “Yeah, sure.”

Texas was hardcore then, just like it is right now. One time I was playing a gig far down in Texas, way down in the [Lower Rio Grande] valley, and they put me in jail. How can a girl be out playing music with a band? And I sat in jail for about six hours. [The police] said, “You don't belong out there, you're underage.” Steve and them got me out.

David Ash: Being Air Force kids, we all had hair to our shoulders. My brother was in a car with the band, sitting at a stop sign. A redneck guy pulled up, grabbed one of the longhaired band members out of the car, and literally dragged him out of the car by his hair and pulled him down the street a block or so.

Lou Cabaza: I remember getting shot at because I had long hair. Over by Andrus's studio, on Broadway and Gulfgate. Andy Szuch (drummer) and I were at a convenience store. And this big old redneck cowboy comes in. I'm looking at the aspirin. He said, “Hey, move.” Not “excuse me,” but “move.” I said, “Go around.” And that was all it took.

I got my stuff—we got in the car, got on the access road of the Gulfgate freeway and here they come in an old convertible Chevy. Next thing I know, they're shooting into the car! And Andy had a Beretta and he's shooting back! I'm in the passenger seat, seeing the smoke from his gun and hearing the bullets whizz by. I'd never heard that. They sizzle when they come whizzing by you. Just the idea of having long hair back then, in Gulfgate? You put life in your hands, many times. Texas was intense back then.

Cassell Webb: Lelan Rogers was so involved because of the studio, and he became our manager. Unfortunately, I signed a paper with him—he became my legal guardian. I was young, you know? Underage. And being underage, I couldn't do anything—couldn't sign a contract. And my parents didn't know the business. So he hustled them. We had to take him to court to get out of it. He had me until I was 21 or 22. [After the Children], it took four years for me to make any steps in any direction. I had to untangle myself from Lelan Rogers. I'd written a lot but he wouldn't let me record. He said, “We can make money if you keep singing backgrounds.”

Lelan was an unusual person. I don't get into it very often about him. Because he helped a lot of bands and did some brilliant things . . . as long as he got paid for it. Not that I didn't have a great time with him, but all of a sudden it turned . . . when I found out what was going on. He took the money. But I learned a lot. The business has always been what it is. Laramie records? Davy Jones got all messed up by them. Anyway, the record (Rebirth) went to ATCO.

Lou Cabaza: Lelan was known as the silver fox. And, yes, he was a shyster. And so here we are again with these corrupt managers. First Davey, then this. But soon after we got hooked up with Lou Adler.

Brewster McCloud & Lou Adler

Brewster McCloud, the zany 1970 film directed by Robert Altman, was shot in Houston and produced by famed LA mogul Lou Adler. By luck and circumstance, some of the Children ended up not only featured in the film, but also signed to another record contract.

Johndavid Bartlett: Shelly Duvall [actress] ran the record booth at the student union at the University of Houston. She and I went together for a little while, then she went with my best friend, then she went with a friend of my best friend, who she ended up marrying. You know, those hippie days. Her eventual husband was Bernard Sampson, and his parents, wealthy attorneys, were having this huge Halloween party up in Memorial. There were lots of hookah pipes. I was the musical guest that night. Anyway, Robert Altman and Lou Adler showed up at that party. They arrived in a burgundy Rolls Royce. They discovered Shelly that night and they cast her in Brewster McCloud. Then they all moved out to LA. Shelly was the one who convinced Lou Adler to talk to the Children and especially Cassell.

Cassell Webb: We were on the last float in Brewster McCloud. That's the first time I met [Altman]. I saw the film being made. It was absurd. It was made absurdly, something I'd never experienced. Just letting people do what they do, which is what Altman always does. Lou Adler was there—that's when he heard our music. Different things appeared and, well, he appeared too. We were on Ode records after that.

Lou Cabaza: I wasn't in Brewster McCloud. I guess some of the other folks were. Anyway, Adler came to our house and said, “I want you guys to come out to LA. You don't need a bass player.” And he sent me one of the Doors touch basses. Ray Manzarek's touch bass.

Cassell Webb: So we went back to LA. Our roadie, Richard Moore, put all our gear into a hearse. And guess who rode with him, haha. Landing in LA in a hearse is a very interesting way to go. If you get stopped by the police, it's like, “Hey what’s going on?” There was no rock star treatment. A little. For the boys, it was a little bit easier, shall we say.

Steve Perron: When we landed in LA, we were picked up at the airport by a Rolls-Royce that had a cassette movie player in the back with quadrosonic sound and an ice box and there were photographers everywhere and they took us right to see Hair and we met the cast. Adler treated us right, and it was all so fast. He put us in the studio and let us record what we wanted.32

Lou Cabaza: Adler didn't laugh a whole lot. He was pretty serious. We got out there in two limousines. We thought, wow! We've arrived! We got to the Landmark Hotel, across from A&M records, and we go over to A&M and they give us $500 apiece. Big money! I didn't even have to pay for my hotel room so I thought—we're doing great. I remember we were on the balcony of the hotel room and this cab pulls up. Kenny [Cordray] gets out, he's 14 years old—he's got a new haircut, new jacket, boxes of shoes, and he spent all his money in one afternoon shopping! We had never seen money like that. It was blowing our minds.

Miles Perron: When they went to the studio in LA and Adler showed up, he walks in and throws these paper bags at them. Like a party favor. You'd expect maybe a day planner in there or something. And instead inside the bags was every kind of drug you could imagine. Anything and everything you could ever want. This was his “welcome to LA, welcome to my studio” gift. But he made them promise they wouldn't take it until after the session.

Johndavid Bartlett: Shelly Duvall hooked me up with Lou Adler, too. I got to play with the Small Faces for a few nights. I did lots of demos with Danny Thomas, Stacy Sutherland, and Duke Davis. I was shopping that stuff for publishing. Ran into the Children a lot in LA at that time. Steve and Louie were hanging out with this band Christopher. Great band. But I had to leave LA. They were keeping me high and happy but . . . I wasn't making music. I was making something else. Making a Hollywood lifestyle. It was too much. It wasn't a love of music, it was a love of “who's got a swimming pool?” That guy from the Carpenters wanted to adopt me. That was strange.

Cassell Webb: Frank Zappa helped me once. The Children were playing with Albert King—we were the psychedelic band. Zappa was playing, too. And all of a sudden there was a huge influx of police. And Zappa said, “Come with me. You can't be here, darlin. Get in the car.” And he put me in his semi-limo. The show was being torn apart. And then when I ran into him, twenty something years later, I said, “Thank you.”

Lou Cabaza: Lou Adler had us do some tracks. We were trying to do another album but unfortunately drugs got involved. Our lead singer kept disappearing. We left LA, had to come back to Texas again. And that's when the real problems starting kicking in.

Miles Perron: Adler forced the band, much to their dismay, especially my dad's—to add flute to their singles. They hated the flute. Hated it! It almost broke the deal. Adler told them, this is what's happening on the radio, this is the sound. Gotta have that flute.

Back in Texas

From 1970-‘72, following the flower-power era of their Rebirth album, the Children reached what many folks consider the peak formation of the group. They had fallen back into San Antonio to write and rehearse material for the final stage of the group. Several high-profile tours had been arranged. But they mostly ended badly. Their renowned live show was never properly captured. During this brief window, they were one of Texas’s top rock bands. Lou Cabaza, one of the original members, left to pursue other opportunities.

Steve Perron: The group represents the end result of my creative channeling, after five years of playing in crummy little groups, getting spit on, beat up, cleaning the vomit off the PA stands, fraternity parties, having long hair in Texas, etc. I wanted the second album to be happy. The first album was very sad, really. Actually, I was very, very politically motivated then, and very peacefully motivated; love, flowers, dissent, Timothy Leary, etc. Now most of my friends are junkies or prisoners, phony flower children or insurance salesmen; and rumor has it the rest are completely crazy. People are on fire and my tranquilizers just came from the drugstore. So I guess I don't have it so bad. Maybe I can grow a moustache, or maybe even form a cult. I have so much to say.

Lou Cabaza: The last version of the group, this was the best version of the group, with Kenny Cordray and Jim Newhouse on drums. After we'd gone through the Argyles and this and that, we finally arrived at our sound! That was 1969, 1970. We were in Houston, working with Adler. We were living in a really nice house there in Houston. The McGregor House. We were living behind the Shamrock Hotel, off Main, over by the Astrodome. Beautiful house but we didn't have any furniture! No gigs, weird drug issues with Steve. He kept disappearing. Anyway, I started getting hungry. And had to find a gig. I had to do something just to eat!

Last Phase

After Lou Cabaza's departure, the band entered its final phase. Steve Perron, reeling from his addictions and a bout of hepatitis, moved back to San Antonio with his family.

Miles Perron: I grew up in a house in San Antonio on Estes Road, right off the Olmos Dam. At the corner of Estes and Abiso, that was our house. We had this huge living and dining room and my dad had speakers in there, reel to reels, tube amps. The Children would come over and rehearse. Kenny Cordray, he was my buddy in the band because he was a kid too! And then random people would come over. The musician community, the “herbal American community.” They all seemed to find each other. Willie Nelson came by one day. Got a picture of him hanging out in our living room. Chris Geppert used to come over, he would hang out. He's now known as Christopher Cross.

I grew up around rock and roll and never thought twice about it. I used to go to other people's houses and tell my mom, “These houses smell funny.” And my mom used to laugh about it, because those were the houses where people didn't smoke weed—it smelled normal. All I was ever used to was incense burning, VW microbuses in the front yard. It was growing up with a bunch of hippies! Like being in an episode of Scooby Doo. To me, it was nothing special. I had to grow up and meet other people to realize how different it was.

Lou Cabaza: Steve and I wrote so many songs that nobody ever heard. Wonderful songs, like Broadway songs. But then he got on this Rolling Stones kick and wanted to be Mick Jagger. And the Rolling Stones don't have a keyboard player! I was the Children's keyboardist and bass player, like the Doors’s style. But Steve didn't want to do that style. That's when he wrote “Francine.” There's no piano in “Francine”! And all the songs we did before were very keyboard based. So, taking that away, it wasn't as fun to be in the band anymore. I know it was the damn drugs taking over. Then Steve brought in this guy Kurt Lindhof, he was very cunning—he really wanted in the band. And he was into drugs too. So, once he got in the band, I started looking for something else.

Steve Perron: Louis said he signed some contracts with some pizza parlors. I said okay, what about next weekend at the Whisky? Adler had us this gig at the Whisky, our California “debut.” Louis said he was sorry, he couldn't make it. I had a knife, I had pulled a knife on him earlier, you know, just kidding around. We used to kid around real violently. . . . Big deal. So he quit. That was it.

The Children cancelled their California “debut,” much to the disappointment of Lou Adler. Immediately following, they'd been contracted to do a tour with B.B. King. Kenny Cordray got injured in a car accident, so Billy Gibbons (of ZZ Top fame) took his place on the ill-fated tour. While on tour as part of the Children, Gibbons learned "Francine," a song which later gave ZZ Top their first bona fide hit reaching number 69 on the Billboard charts.

Steve Perron: That [tour] was when I got back into the drug scene pretty heavy. . . . At the end of that tour I was pretty well knocked out and depending on Adler to come through for the band. We did have a hit single and I've written maybe 700 songs and had 200 of them published and two of them were hits under Adler. He did get the job done as far as promo and all . . . but he never really gave us a chance.

Lou Cabaza: After I quit the band, Steve and Kenny wrote “Francine” and Billy [Gibbons] picked that up. They finally got their royalties but it took quite awhile.

Miles Perron: That song sounds a little inappropriate, but “Francine” was about a girl my dad knew when we was in junior high. Dad and Billy Gibbons were very good friends. Billy Gibbons considered my dad the best songwriter that he personally ever knew. That's what I was told anyway. So Billy was always looking to Dad for ideas.

Galen Niles: How Billy Gibbons learned “Francine” was Cordray injured his arm or something like that, couldn't go on tour with the Children. They had a tour backing up BB King. They asked Billy, “Hey will you go on tour?” He said, “Sure.” And he learned “Francine” which was on the Children's set list. And that's where he got it. It became ZZ's first successful hit.

Miles Perron: Bill Ham went to bat for my dad, after he died, with Lou Adler. Ham had a lot on his plate and didn't need to do that. So it meant a lot. Billy was involved in that as well. Billy was always really sweet to my mother. Anyway, they went to Lou and said, you've got to make this right. You need to get some money to Steve Perron's widow. I remember walking in, sometime around their album Eliminator, and my mother was holding a letter and crying. She had finally gotten paid.

End of an Era

The Children fizzled out, amidst mismanagement, drugs, and tragedy. This tragic aspect potentially explains why so few people know or talk about the group today.

Cassell Webb: Drugs—it was part of that life. There's just no way around it. That era of time—the psychedelic era—it wasn't as long as people think. Two or three years—that was really it. And if you were lucky, you went one way. And if you weren't . . . you went another.

Lou Cabaza: Steve was my best friend but the drugs ended up taking it away. I had to fight to get credit on “From the Very Start,” which I did with him, and I know it was the drugs. On the other side, I hate to say it, but the drugs were somewhat responsible for the vitality of the music. It took your mind completely somewhere else. And that's what the psychedelic era was completely all about. I stopped though—I got saved. For a lot of guys it didn't work—they did the wrong thing and they were dead. A friend would take a step to the side and never get back up. And the ones that did, they weren't very successful. People blowing their brains out with acid.

Phil Krumm: I loved acid. Loved it. I had a lot at the appropriate time, back in the ‘60s, when it was the good stuff. I learned all my psychic lessons and had great respect for it. It never hurt me. . . . It was never anything but nice to me. No matter the environment, a bunch of wonderful people or a bunch of monkeys—it always pulled me together. That was the initial effect I got from it—togetherness. It said . . . “you're very sane. Don't worry about it.” I loved it. I loved acid.

Cassell Webb: It transitioned into other things. You could see it flowing. Started as psychedelics then the hardcore people came in and took things over—pills, heroin. You saw them coming in the backdoor. The harder drugs. You could see that very early. I saw Jim Morrison at the Whiskey. One time I saw him absolutely together. Seven months later, he was on the floor.

Johndavid Bartlett: I can testify to Steve Perron's talent and vision. His and Cabaza's both. There's no telling what would've happened to Steve, had he lived. That's the demon side of it. The hellhound on your trail. That's why I came back from LA. I dreamed it, actually. Dreamed of hellhounds.

Miles Perron: Dad was sending off tracks to Lou Adler for songwriting. Crystal Gayle was trying to buy one of his songs, one from the Adler deal, I believe it was “Such a Fine Night.” Then Dad died and the deal never materialized. Had my dad not had all the drug stuff, I'm pretty positive he would've made it big, if not as a performer, as a writer at least.

Cassell Webb: When Steve and Benny, all those guys, got so involved in drugs and LSD, you knew it was numbered. It's not something I was that heavy into. I took different roads . . . in the same place. I wasn't that into drugs. I was so used to taking care of people in bands. I did quite a bit of that.

Galen Niles: Treiber was on Lake McQueeny in his speed boat. He hit a log or something, flipped him over, and it killed him. He was one of those casualties. Rock music had a lot.

Lou Cabaza: Kenny Cordray, his son ended up killing him. Then turned the gun on himself.

Johndavid Bartlett: The airy part of the Texas psych scene, like the Children and Golden Dawn, that stuff was a huge influence for prog bands. I look at the Texas psych scene as one of the great creative moments in human history. It was a time when all bands interacted in one way or another. We were all in the same places. There was a community. That's what fed that creative bubble. Some of the recordings are unbelievably great. And the Children were one of those bands. A great live band, a live experience they were trying to capture in the studio. They didn't have the technology or even the ears to necessarily capture it. But it came close.

Cassell Webb: The Children fizzled, everything fell apart, my life changed. I always remember it, respect everybody in it. Lost so many people, cried so many tears. Steve with his problems, lost two drummers, Kenny Cordray. It's hard. Never could get people to totally accept our band, due to changes in the culture, where music was going. It was the good, the bad, and the ugly. And it got very, very ugly. We all stand in those corners at times. A lot of this area of time is very life changing for me and very sad . . . but very open as well. I still have many fabulous, loving friends from that era.

After the Children

The Children were one of the great Texas bands of the late ‘60s, with their live performances legendary among those in attendance and their music tracing the scene's evolution from garage to psych to ‘70s style rock (with a capital R). If the story ended here, their legacy would be secure, if only limited to devotees of San Antonio history, garage rock, and psych rock. The story continued, however, with various members of the band achieving success in the wider music world. The Children provide a direct link between Billy Gibbons, Natalie Cole, Blondie, the Fall's Mark E. Smith, and Pavarotti.

Cassell Webb, in particular, surfaces as one of the major musical figures ever to emerge from San Antonio, worthy of a place in the Alamo City pantheon, alongside Doug Sahm, Augie Meyers, and Flaco Jiménez. The fact that she's barely known in her hometown is both puzzling and appropriate. As she emerged into her own career, she transcended her hometown. From progressive country to post-punk to modern classical, Cassell Webb has engaged with music on a world stage, working with the finest and most innovative artists while pursuing her own outstanding solo career.

After the Children's demise, Webb began singing backup for a who's who of Austin's burgeoning cosmic country scene, including Jerry Jeff Walker, B. W. Stevenson, Townes Van Zandt, and Willie Nelson. She later became manager of Jimi Hendrix's Electric Ladyland Studios in New York City, where she began a romantic and artistic collaboration with Craig Leon, famed producer of the Ramones, Blondie, and Suicide. Together, they moved to Europe, where Cassell released numerous records under her own name and continued production work with Craig Leon, including work with post-punk group the Fall and opera star Luciano Pavarotti. More recently, Nommos, an album they recorded in Willis Alan Ramsay's Austin studio in the late 1970s, has gained notoriety amidst a resurgence of interest.

Progressive Country and the Armadillo World Headquarters

Finding herself in the right place at the right time, Webb transitioned from folk to garage to psych and finally to Austin's emerging progressive country movement, centered around the Armadillo World Headquarters. Ever the survivor, she entered a new phase of her career.

Cassell Webb: At that time, there was a whole conglomeration of a lot of different styles. A lot of people came together. . . . People were saying things they hadn't been able to say before—you can hear it in the lyrics and in the presentation. Finally, folks weren't afraid to just go in and do it. That's how it was made. This was happening all over, but it was the first time in Texas—this little area, a tiny area—near Sixth street in Austin.

The Armadillo, when it opened, I was there. I would work at the Armadillo quite often to make extra money. Worked in the stage crew. The door opened on all kinds of music. Every night a different genre. And Austin started coming alive.

I was a folk singer. To make it, you had to scramble, do things in the short term—gigs and such. Then B. W. Stevenson showed up, Freddie Krc, Rod Osborne, great musicians, great friends. The whole crew. Great band. And there I was singing country folk music again. It was like going back to folk music to me. Rock and roll is folk music. It's what you're walking in, it's what I'm walking in.

We all got on a train [to LA] after we'd played with B. W. for a while. And that was when we met Guy [Clark] again. Tommy Lapluna and Al Schwartz, brilliant engineer. And we did that [B. W. Stevenson] record with him. That was quite a challenge. It was that real smooth, B. W. kind of voice. He was a great singer, walk in and do it in two takes. But he was a real heavy drinker. Sometimes he was right on top of it, and sometimes you'd think, are we gonna get through this job at all?

I started writing songs, hiding them in the background. I'd done psychedelic, now country and my own music secretly in the middle of all of it. I started working with Guy, Townes Van Zandt, Willie, and B. W. Stevenson. When I was working with Guy Clark, I met Craig. We met each other over a pool table in San Antonio. He said, “You have great ears.” I said, “Well, here they are.” Al Schwartz said that to me also.

Craig Leon: I was doing a lot of country. I don't care about genres. Country, folk, punk, classical. It's all the same to me. It’s all just making noise out of sound. Anyway, I did a record with Rodney Crowell. We had a country hit or two on that album. He hooked me up with one of his friends, Guy Clark. We were doing Guy's album in Texas and, in the studio, Cassell and Bonnie Bramlett, from Delaney and Bonnie, they did backups. That's where I got to know Cassell, who told me she wanted to get out of Texas.33

Electric Ladyland

After doing backup vocals for many years, Cassell Webb found an opening—a way out—towards her own career as solo artist and producer. Her journey took her to NYC, where she produced an album with her old friend Doug Sahm in 1981.

Craig Leon: RCA wanted me to find another Texas artist. Lenny Waronker said, “If you can find Doug Sahm, tell him he contractually owes us a record . . . and he should make it with you.” I knew Cassell was from San Antonio and she had a connection to Doug. I told her, if you can find Doug, you can help me produce. Two or three days later, Cassell shows up in the studio with five guys in full baseball uniforms. It was the Sir Douglas Quintet! They were part of a softball league in San Antonio. They were playing in the park and she dragged them straight over. We went to New York and Doug stayed at our flat in the village. He ran up a $10,000 phone bill calling DJs all over the country saying “Hey, how are you out there in Montana? I'm making a new record.”

Cassell Webb: I took Doug Sahm to record up there. Said, “You got to meet these people up in New York and make a record.” The band hadn't played together in four or five years. Border Wave, that was Doug's comeback. I learned a lot from him. He just loved music so much. He'd write songs and write songs and put them on the wall and made plans of where to play. Doug and I were such great friends. Doug would spend all night on the telephone. You couldn't believe the conversations. “What do you mean, Bob Dylan?” and click, he hung up. And then, “You tell that kid in the Ramones it's Doug.” Click. Absolutely brilliant.

When I moved to New York, I ended up running Jimi's studio, Electric Ladyland, for almost a year. The Hendrix family was taking over. I was up there right after he died. I found a gold record behind a black wall. It was Are You Experienced? Most people thought I was a bit strange to give it back, but I called his parents and said, “I've got this record—it's yours. I want you to know. It's in the back.”

I'd actually first met Jimi when he did these two concerts in San Antonio. Me and my boyfriend sold him a guitar. Got some great photos of him at the Satin Doll [San Antonio bar]. Kurt and I, we went into that gig, I was carrying the guitar for him. Jimi wasn't that huge then, but just a great musician.

Nommos