JTMH Volume 23 | Robert Earl Keen

The Last Filling Station: Robert Earl Keen's Texas

Rich Kelly

As August turned into September in 2022, Robert Earl Keen was winding down his I’m Coming Home Tour. The six-month farewell run culminated in a surprisingly rainy three-day Labor Day weekend stand at John T. Floore’s Country Store in Helotes, Texas. Floore’s had been the site of Keen’s legendary 1992 Live No. 2 Dinner, a key moment in the Texas legend’s career and the Viva Terlingua! for a new generation of homegrown Texas Country artists Keen inspired to revive the progressive country era that had inspired Keen himself.1 Keen’s final show even featured one of those he inspired, Brendan Anthony, longtime fiddler in Pat Green’s band and current head of the Texas Music Office, presenting one of his heroes with an official proclamation from the State of Texas honoring the songwriter. In the week leading up to that final show, Keen wrapped up his performing career on his own terms.2 Sunday night he showed up spontaneously at Austin’s legendary Continental Club, established in 1955, with band in tow and asked management if they minded if he got up and played a few songs. He explained injuries and weariness were ending his touring career and he always really liked the place. Three days later he popped in a little further south on Congress Avenue for one last (unannounced) coffee house gig at Cosmic Coffee.3

As a young man, Keen explained, his hero had been rodeo hall of famer Phil Lyne. Lyne had retired from rodeo in 1972 at the age of twenty-five after winning his second consecutive world championship. Keen admired Lyne, who spoke at Keen’s final show, for walking away early to raise his daughters on his ranch while he still had his health. Keen’s back had given out the year before making performing painful, a problem that worsened with a series of allergic reactions to the medicines prescribed to treat the pain. While Keen remained a potent live draw, at the age of sixty-six, the beloved singer had little left to accomplish.4 Since his debut release in 1984, Keen has released twelve studio albums along with seven live albums. He is considered a major figure in the birth of one genre, Americana, and the founder of a second, Texas Country. In 2009, artists inspired by Keen recorded a tribute album, Undone: A Musicfest Tribute to Robert Earl Keen. His songs have been covered by dozens of artists ranging from superstar George Strait to country supergroup the Highwaymen to crossover juggernauts the Chicks. He has been honored with a BMI Troubadour Award and as a distinguished alumnus from his beloved Texas A&M University, and inducted into the Texas Heritage Songwriters and Texas Cowboys Halls of Fame. Keen boasts nine appearances on PBS Austin City Limits broadcasts and a pair of Texas Monthly covers. Long before he walked off that stage in Helotes for the final time in 2022, he had helped redefine country music in Texas and beyond.

Both the music scene that Keen emerged from and the one he largely inspired were rooted in notions of embracing an imagined historical Anglo-Texan identity in a time when urbanization and homogenization were radically transforming the state from a cotton, cattle, and oil culture into an urban and suburban high-tech center. During the 1960s, Archer City, Texas, native Larry McMurtry began a career that would make him the Lone Star State’s most revered author by wrestling with this issue. Between 1961 and 1966, he published “three short elegiac novels, all of which dealt in a small way with a large theme: the move from the land to the cities (or the small town to the suburbs).” Horseman Pass By, Leaving Cheyenne, and The Last Picture Show each approached the subject by way of literary metaphor. In 1968, McMurtry addressed the subject directly in his book of essays, In a Narrow Grave. In the introduction, McMurtry explains that even as a teenager, he realized he was witnessing the death of a “rural, pastoral way of life.” McMurtry and his early protagonists all were fascinated by their own distorted ideas of Texas’s agrarian past since “the myth of the cowboy grew purer every year because there were so few cowboys left to contradict it.”5

McMurtry also had no illusions about the future. “The city will win, of course, but its victory won’t be cheap—the country traditions were very strong.” To be young in Texas in the latter half of the twentieth century was to negotiate these two forces. McMurtry prophesied, “The descendants of the trail-hands will be driving beer trucks in the suburbs of Ft. Worth, Dodge City, Cheyenne and a score of other cities whose name once held a different kind of promise.”6

In his book Progressive Country: How the 1970s Transformed the Texan in Popular Culture, Jason Mellard argues young Anglo Texans responded to this transformation of their native culture by “performing the Texan.” “Texanness,” Mellard posits, is “in part, a performance, a set of strategies and gestures, some conscious, some not.” Young adults typically experiment with potential identities. They explore various social groups, modes of dress, speech, and music. For young Texans, this commonly includes identifying themselves with cultural markers associated with their home state such as cowboy boots; outdoor activities such as hunting, fishing and camping; and the state’s native music. Periodically, McMurtry’s beer truck drivers play out their mythological cowboy past en masse. The scenes that developed around Bob Wills and a host of singing cowboys in the 1930s and 1940s and the progressive and subsequent outlaw country scenes of the 1970s are two prominent examples of this phenomenon.7 At the turn of the millennium, “performing the Texan” through the celebration of Texas music and its attendant culture once again took center stage for a new generation of young Texans.8 Robert Earl Keen, the key figure in this revival, was first a fan himself, “performing the Texan” in his own right during the days of Willie Nelson, Waylon Jennings, and Jerry Jeff Walker. Inspired by these 1970s Texas icons, Keen toiled in relative obscurity for almost two decades before becoming a founding figure in the Americana movement and the undisputed patriarch of the Texas Country scene.9

Sharpstown, a suburb in southwest Houston, was literally a prototype of the new suburban Texas McMurtry wrote about. Built to accommodate Houston’s growing Anglo-middle class professional population, Sharpstown was one of the nation’s first master planned communities. In 1955, developer Frank Sharp set aside land for schools and retail outlets, as well as donating land for the construction of US Highway 59, ensuring a commuter route into Houston. In its early days, Sharpstown was thought to be the biggest suburb in the nation and boasted the state’s first air-conditioned shopping mall.10

It was into this aspiring utopia that Robert Earl Keen, Jr. was born on January 11, 1956. Keen was the second of three children of his geologist father and attorney mother. Keen was drawn to music from an early age, composing an ode to Larry’s Mexican Food Restaurant when he was just eight. Through his parents Keen was exposed to country and folk music such as Jimmie Rodgers. The minimalist approach of Rodgers shaped Keen’s style. “I loved his sound, just his guitar and voice.”11 Like McMurtry’s urbanizing Texans, the Keens strove to maintain their connection to the fading rural Texas culture. They often spent weekends at the family’s retreat near Columbus, a small Texas community midway between Houston and Austin on Interstate 10. There, the young Keen enjoyed spending his evenings watching and listening to the Czech and German polka dances.12

In middle school, Keen’s taste evolved more towards the popular rock music of the time, such as Cream and the Beatles.13 By high school, Keen’s brother Dan, nine years Robert Earl’s senior, turned on his younger brother to country music. Hank Williams and Buck Owens, along with Rodgers, were favorites of the Keen brothers.14 Keen found a kindred spirit in his “best friend since the third grade,” Bryan Duckworth.15 As teenagers, Keen and Duckworth would cruise Sharpstown listening to Rodgers, Bob Wills, Ernest Tubb, and other early country stars.16 Soon the pair added bluegrass music to their playlist, further embracing largely acoustic traditional forms of music. For Keen, this process of exploring his influences’ influences was his way of connecting to both his Texan identity and mythologizing a preindustrial past.17

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, Houston, as the headquarters for NASA and a key city in the oil industry, rapidly embraced modernity and the high-tech economy that came with it. Houston professional sports teams of the time boasted names reflecting this: Oilers, Astros, Rockets, Aeros, and Stars. Sharpstown High School, where Keen graduated in 1974, took as their mascot the Apollos. While Houston reached for the heavens, Keen and other Anglo suburbanites fixed their gaze squarely on the agrarian past. Country and bluegrass music came to represent this vanishing culture.18 Keen’s interest in country music mirrored a national trend towards country rock.

Ushered in by Bob Dylan’s 1967 release John Wesley Harding, mainstream rock acts such as the Byrds, Poco, New Riders of the Purple Sage, and the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band embraced country elements in a style dubbed country rock.19 Michael Coyle and Jon Dolan see this artistic choice as a protest of the commercial aspects of the music industry that was, ironically, highly profitable. “The turn of these new bands to countrified or folkified rock was meant to signify rejection of consumer culture and it proved a commercially substantial gesture.”20 In his history Stayin’ Alive: The 1970s and the Last Days of Working Class Culture, historian Jefferson Cowie argues the former hippies’ embrace of country music and imagery was a manifestation of their failed attempts to raise the consciousness of blue collar Americans. In the chapter “I’m Dyin’ Here,” Cowie surveys popular music of the late 1960s and early 1970s to argue that during this time well-meaning liberals turned to their rural roots in the form of country to reach out to the common working people they believed they could construct a utopia for and with. In a powerful deconstruction of Jackson Browne’s “For Everyman” (1973), Cowie sees Browne accusing liberals, overwhelmed by the task, abandoning the common man and seeking their own “peaceful, easy feelings” in solitary rural (or suburban) existences. This California brand of country rock, led by the Eagles, quickly abandoned its rustic qualities in favor of a smoother sound before drifting back towards rock by the mid-1970s.21 Texas, with its rural past so near and mythology so alluring, was particularly susceptible to this sort of logic. As Jan Reid explains in his genre-defining study The Improbable Rise of Redneck Rock, “The craze for nostalgia, to get away from it all, engulfed almost all popular forms of American expression, and in Austin, the musical retreat led naturally enough to country and western.”22 Larry McMurtry wrote about his own youth, “Intellectually I had long been a city boy, but imaginatively I was still trudging up the dusty path that led out of the country.”23 As the seventies dawned, Keen walked a similar path.

During high school, Keen's younger sister exposed him to Houston’s singer-songwriter scene. Still too young to drive, Kathy Keen established herself as a legendary foosball player in downtown Houston. Robert Earl served as her chauffeur.24 While his kid sister dominated the tabletop pitch, Keen stumbled upon his future. Keen recalls in the downtown bars “there was always some guy or some girl or some duo playing really cool guitar and vocal music.”25 Taxiing his sister, Keen heard Willis Alan Ramsey, Mance Lipscomb, Lightnin’ Hopkins, Talking Heads, and numerous forgotten performers playing simple, acoustic performances in coffeehouses and lounges all around Houston. He discovered Anderson Fair and other venues that featured singer-songwriters.26

Keen was exploring the remnants of Houston’s influential 1960s folk scene. This scene emerged from the Houston Folklore Society’s monthly Hootenannies. Real estate developer John A. Lomax, Jr. led the organization. Lomax had traveled with his father, who pioneered the practice of canvasing the South and recording folk songs in the 1930s. The senior Lomax had recorded hundreds of folk singers, including the imprisoned Lead Belly, while establishing himself as one of the founding fathers of the study of folk music.27 His son was an amateur folklorist who organized and performed in the Houston “hoots.” Exalted bluesmen Lightnin’ Hopkins and Mance Lipscomb were two of the stars of these Sunday performances. Future Texas songwriting legend Guy Clark was a regular. “John Lomax [Jr.] was always at Hermann Park, and we’d sit around in the summertime, just twenty or thirty people in circles singing songs,” Clark recalled. Soon a string of coffee shops and lounges began hosting the folkies, including the Jester Lounge, Sand Mountain, Anderson Fair, and Galveston’s the Old Quarter. Hopkins, Lipscomb, and local white musician Frank Davis were the scene’s biggest stars. Future country superstars John Denver and K.T. Oslin spent some time making the circuit as well.28

Three performers, unknown at the time, would become central figures in the progressive country scene of the 1970s. Guy Clark moved to Houston from Rockport, where he met Townes Van Zandt playing the small clubs. The two began a friendship that would last until Townes’s death on New Year’s Day 1997. The scene was key to the artistic formation of both artists who incorporated elements of the blues and folk they witnessed into their long and celebrated songwriting careers. Clark and Van Zandt also made the acquaintance of a rambling New Yorker who had reinvented himself as Jerry Jeff Walker after going AWOL from the National Guard to pursue the romanticized life of a wandering folksinger. These three were among the most revered songwriters of the progressive country scene that Keen would champion in the following decades.29

By the time Keen arrived, Clark had moved to Tennessee to write songs for a publishing house. Van Zandt and Walker had rambled on to resurface in Austin. All three still routinely played the small clubs in Houston where Keen first saw them.30 By 1974, Keen’s senior year of high school, his older brother had converted Robert Earl into a rabid progressive country fan.31 Centered in Austin and associated with the famed Armadillo World Headquarters, the progressive country scene Keen embraced as a fan was populated by “middle class youths who hailed from Texas’ cities, but as such they were rarely more than two or three generations removed from more rural times.”32 Like Keen, these young suburbanites in their blue jeans, boots, and pearl snap shirts longed to fulfill McMurtry’s prophecy, seeking to perform the Texan by drinking Lone Star beer to Willie Nelson and Jerry Jeff Walker. Performers and participants promoted a “strange mélange of western swing, honky-tonk, blues, Cajun, zydeco, and conjunto music, which became known in Texas as ‘progressive country music.’”33

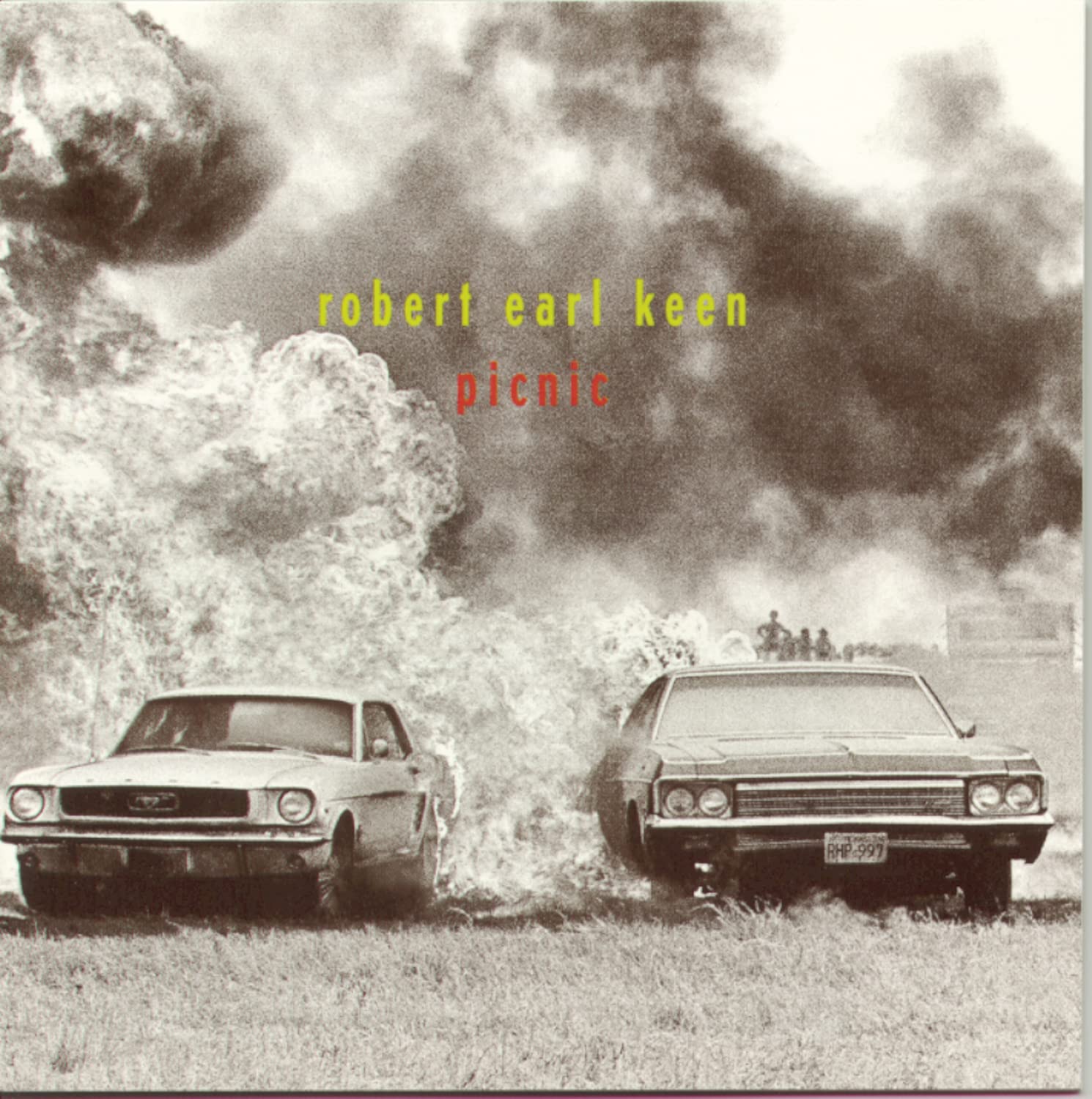

Keen engaged in the progressive country scene whenever possible, even foregoing his senior prom to catch Willie Nelson at Houston’s Half Dollar Club.34 In the summer after graduating high school, Keen drove his Ford Mustang to Texas Motor Speedway near College Station for a three-day celebration of Texas music and Texan identity. Willie Nelson’s second Fourth of July picnic featured a massive lineup including Kris Kristofferson, Waylon Jennings, Jimmy Buffet, Townes Van Zandt, and the Red Headed Stranger himself. Even Ricky Nelson and his Stone Canyon Band made the show, representing the California brand of country rock.35 Keen awoke from a debauchery- induced nap to discover that the drought-parched grass where he had parked had caught fire, and his Mustang had burned up. He lost a car that day but did get to meet a sympathetic Willie for a brief moment before Nelson had to go jam with Oklahoma great Leon Russell. Over the following decades, Keen incorporated the tale into his live shows, ultimately releasing it on 1996’s No. 2 Live Dinner and using a picture, presumably, of his Mustang fully engulfed in flames for the cover of 1997’s Picnic.36

In the summer of 1974, Keen picked up a gut-string guitar discarded by his little sister.37 Between high school and college, he went to work in the East Texas oil fields armed with his sister’s guitar and a book of songs. Among the first songs Keen learned to play was Nelson’s “Hello Walls.”38 Pleased to see their unfocused son dedicating himself to anything, Keen’s “notoriously cheap” parents shocked the budding musician by buying him an expensive Martin D-35 guitar.39 Touched by his parents’ support and driven to play music, Keen practiced his precious gift non-stop. Keen had routinely won prizes in school poetry contests and applied these skills to songwriting. The first “real” song Keen recalls writing was a Jimmy Buffet-style tune about working in the oil fields that has not survived. It was during this time Keen decided what he wanted to do with his life. He pondered a future as one of the “ants” working in the oil business. “I didn’t have any interest in following in [my father’s] footsteps, though. I was more interested in music, art, writing, and happy hour.”40

As a recording artist, Keen is inextricably linked to his alma mater, Texas A&M University. He recalls being ambivalent about where to attend college. Despite coming from a family of University of Texas Longhorns, he simply followed his best friend out of Sharpstown to College Station.41 Keen switched his major to English after realizing how much math and science was involved in an animal science degree. In his early years in College Station, the primary thing Keen learned was there was no supervision in college. “I could spend all my time watching TV,” Keen recalls.42 “I got kicked out of school a couple of times. They never really offered any assistance; they just booted you. The second time I got kicked out, I found a pamphlet offering study help, but it said they were meeting at the Dixie Chicken. That really wasn’t what I needed!”43

While Keen neglected his studies, he focused on his music. New friends expanded his musical horizons. “We ran into some kids who were from very rural areas,” Keen explained. “We were from Houston, you know, so we were city slickers, but these kids were from places like Pampa and Levelland [Texas]. They loved country and bluegrass and western swing, and they’d be playing fiddle and mandolin, and it was great.”44 Keen and Duckworth rented a run-down house on Church Street across from the Texas A&M campus in the North Gate section of town which became the nexus of a collection of young Aggies united by their interest in country, western swing, and bluegrass music.45 The house and its front porch became a key focus of identity formation for Keen and his friends as they reenacted the age-old ritual of performing the Texan. The house on Church Street has long since been torn down and is now a parking lot.46

The rotating group of musicians who congregated at the house soon coalesced into an attempted bluegrass band dubbed the Front Porch Boys. The group was limited to playing flea markets, church suppers, and other small shows that did not require a public address system.47 The band lacked the instrumental virtuosity required to play bluegrass standards, so Keen turned his attention to writing original music inspired by more contemporary artists such as Willie Nelson, Guy Clark, Jerry Jeff Walker, and Jimmy Buffet.48

In mainstream music, enormously popular bands playing bloated stadium tours to crowds that at times topped 100,000 fans characterized the summer of 1976. Disco music was ascendant with Abba’s “Dancing Queen” taking the prize as the year’s top single. In the second slot was Queen’s epic, operatic “Bohemian Rhapsody” followed by the easy listening smash “If You Leave Me Now” by Chicago.49 Dylan’s Rolling Thunder Revue brought America’s greatest songwriter to massive venues with a cast of dozens, a far cry from his hushed-man-and-guitar early outings.50 The Recording Industry Association of America certified The Eagles Greatest Hits as the first platinum record.51 A few bands, having mastered a magic musical and marketing formula, notched staggering album and ticket sales. Music had been standardized. Modernism was triumphant.

Yet some fans questioned the dominant musical consensus. In New York City’s unfashionable Bowery, the Ramones released their eponymous debut album. They thought it was a retro homage to simpler surf rock and roll, but others saw it as a postmodern deconstruction of the entire rock genre. The Ramones shared the CBGB stage with musical revolutionaries Television, Talking Heads, Patti Smith, and others.52 A few miles to the north Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five became the first hip-hop group to play a major venue, taking the Avalon Ballroom’s stage in Harlem that September.53 An ocean away, a few dozen Manchester youths stared slack-jawed as a ridiculously hostile, pale twenty year old calling himself Johnny Rotten glowered at them. On that single night in July, the Sex Pistols would send the founders of Joy Division, New Order, the Buzzcocks, Simply Red, the Smiths, the Fall, and the revolutionary Factory Records scrambling to launch their music careers.54 In this light, Keen’s rejection of mainstream country is part of a larger rejection of standardized music and a postmodern search for a more personal musical experience.

Down in College Station, 1976 was a pivotal year for Keen as well. One day a journalism and German major passing the porch stopped to listen. Keen invited the young man onto the porch and offered a guitar. The student, Lyle Lovett, made a deep impression on Keen. Typically, Keen spent his summer working in the oil fields, but in 1978, he stayed in College Station to raise his grade point average. Keen and Lovett ended up taking an American literature class together and grew inseparable. Along with their musical tastes, the two shared a suburban Houston upbringing, with Lovett hailing from Klein. Lovett impressed Keen with his musical professionalism. Lovett booked Austin-based singer-songwriters such as Willis Alan Ramsey and Nanci Griffith as part of the Basement Committee, a wandering coffeehouse concert series. Lovett was also already writing and performing his own songs in public. He was dedicated to being a professional musician and developed a solo show which inspired Keen to make music more than just a hobby.55 Keen graduated from Texas A&M with a degree in English in 1978, a year before Lovett. Determined to advance his musical career, Keen journeyed to Austin in 1980 to buy a public address system for the Front Porch Boys. Upon returning to College Station, he learned the band had broken up in his absence.56 Familiar with the capital city from frequent college trips to catch music shows, Keen moved to Austin with his newly acquired PA and immediately began performing anywhere that would have him for tips or discounted meals.57

Lacking a full set of originals, Keen covered his influences such as Jerry Jeff Walker, Willie Nelson, Merle Haggard, Bob Dylan, Richard Thompson, and Loudon Wainwright.58 He found facing an audience alone with just his guitar “incredibly liberating.” Normally shy, Keen was a different person on stage, filling time between songs with the jokes and stories that would remain a staple of his live performances.59 These elements became a major source of Keen’s appeal. Michael Kilian recalled hearing Keen for the first time on a cassette in a friend’s truck. “I thought he was terrible. There really wasn’t much about him I liked, until I saw him live. Then it was just fucking awesome.”60 Another early college-aged fan, Brian Zintgraff, enjoyed Keen’s live shows because the singer was “relatable. The way he told a story was funny. The way he engaged the audience was not how anybody else did it. His thirty-second interlude or story is hilarious. When Jerry Jeff Walker stops singing, he’s going to yell at you if you make a song request.” Zintgraff felt that “Robert Earl was having more fun than most of the people there.”61

Keen landed a job as an oil proration analyst for the Texas Railroad Commission. In just a year and a half he saved enough money to send his parents on a European vacation before quitting his nine-to-five job to pursue music as a career. Keen’s low-level gigs rarely paid more than $25, which meant paying the bills was always a struggle. He routinely worked odd jobs to make ends meet, spending time in construction, as a courier, overnights at the IRS, and other “flunky stuff.”62

The progressive country scene in Austin had cooled by the 1980s. Even the Armadillo World Headquarters shuttered its doors on New Year’s Day 1981. The 1980 film Urban Cowboy boasted a soundtrack that dominated country radio play, ushering in both a city slicker cowboy fashion craze and pop-infused country radio hits.63 While Willie and Waylon still routinely charted singles, the stripped-down bluegrass and western swing style Keen favored was largely out of fashion. The hot acts in town were the blues rockers such as the Fabulous Thunderbirds, Lou Ann Barton, Paul Ray and the Cobras, and ascendant guitar hero Stevie Ray Vaughan. Other live music fans, intoxicated by a San Antonio Sex Pistols gig, began building a small but notable punk scene at Raul’s, a Mexican American bar across Guadalupe Street from the University of Texas.64 Considering Keen’s singer-songwriter aspirations and his remarkable gift for storytelling, these developments were a blessing, allowing him to hone his songwriting and performance craft in front of small, quiet audiences instead of having to compete with the large and raucous country scene of the 1970s.65

Amidst the ashes of the cosmic cowboy movement, a new generation of folksingers emerged playing mainly around Houston and Austin. Keen and his college friend Lovett fell in with these likeminded songwriters, befriending such talents as Steve Earle, Nanci Griffith, Lucinda Williams, Mandy Mercier, and Eric Taylor.66 Keen and his kindred spirits came to idolize expatriate Texans Townes Van Zandt and Guy Clark. The pair of best friends lived primarily in Nashville, where their widely admired compositions appeared on major stars’ records, but the aspiring songwriters back in Texas were far more interested in Van Zandt’s and Clark’s poor-selling but critically lauded albums.67

Ultimately, each of these artists would decide to leave Austin to escape what Earle described as the city’s “mañana attitude.” Earle warned Keen that Austin had “too many pretty girls and too much cheap dope.”68 Even before leaving Austin in 1985, Keen pushed to cultivate an audience outside of Texas. As early as 1981, Keen played small gigs in Chicago, New York City, and Berkeley’s esteemed folk mecca Freight and Salvage.69 The Kerrville Folk Festival also provided an avenue for Keen to showcase his songwriting to a wider audience. Founded in 1972, the eighteen-day Hill Country campout focuses on songwriting and rejects the star system with nationally known artists swapping songs around campfires with novices. Created by Rod Kennedy, the festival has gained an international reputation and fostered the careers of songwriting talents such as Butch Hancock, Jimmie Dale Gilmore, Joe Ely, Guy Clark, Townes Van Zandt, Steve Earle, Terri Hendrix, Lovett, Keen and many others.70 The Folk Festival immediately captured Keen's imagination. “I just packed up my little ’63 Dodge Dart with everything and went out there with a pillow and guitar and slept on the ground,” Keen remembered fondly more than three decades later.71 In 1983, Keen won the festival’s prestigious “New Folk” award, joining previous winners Earle, Griffith, Tish Hinojosa, and his old friend Lovett.72 Keen’s dream of making a living performing his own songs was taking shape.

The least commercial radio station in Austin at the time was 90.5 KUT. Operated by students and staff at the University of Texas, KUT played an eclectic mix of decidedly non-Top 40 cuts. Keen became fixated on the Saturday morning Folkways program and began to wonder if he made a record if the show’s host might play it.73 At the time, making a record without label support was a daunting task. The equipment necessary to record music with enough fidelity for a commercial release was enormously expensive and not readily available. Record producers and engineers with sufficient expertise typically worked with labels in high-dollar studios as well. In the 1980s, however, the cost of making a record had fallen to the point where independent record labels had proliferated across the nation. The ubiquity of these, often tiny, alternatives to major labels is perhaps the most significant development in music of the decade. For example, both alternative rock and hip-hop hinged on independent label support. Even with this expansion of opportunities for non-label acts, self-produced records remained a rarity.74

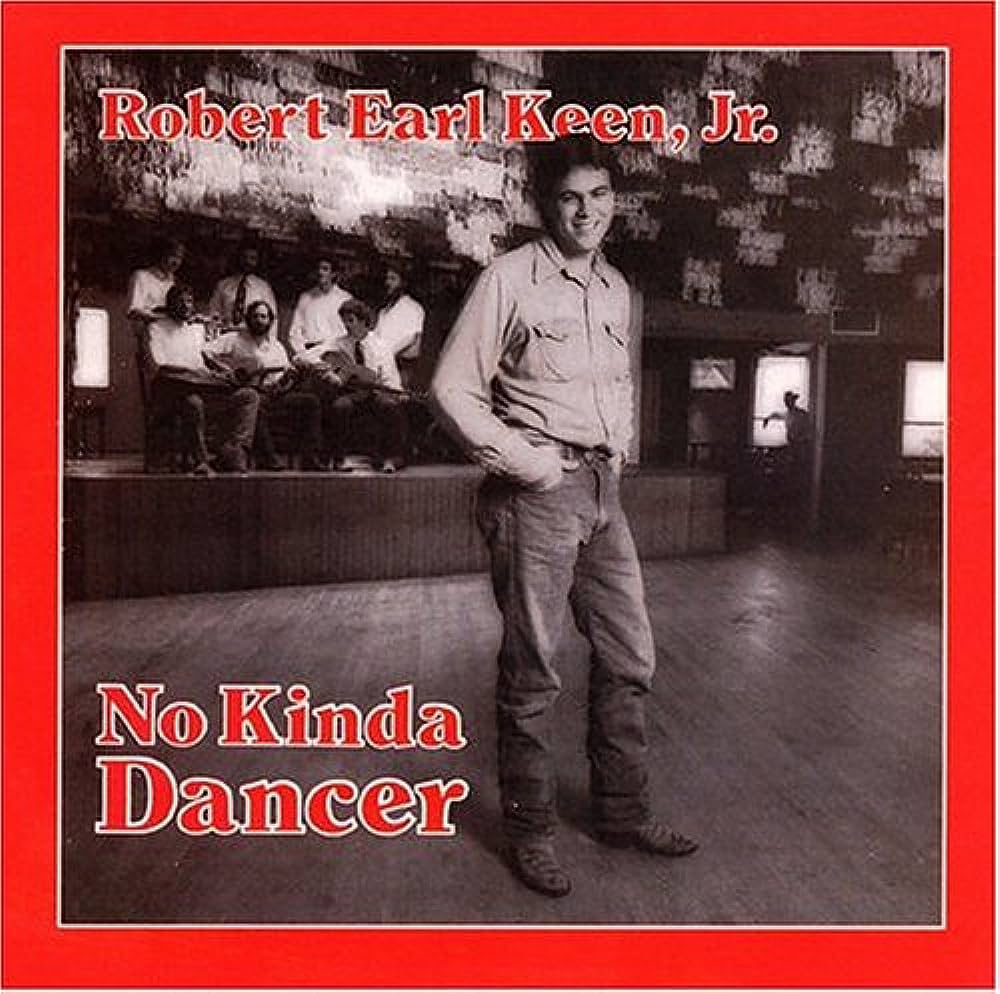

Guided by a book called Making Your Own Record, a gift from Lovett, Keen tapped friends and fans to support his debut release.75 The ambitious artist drafted a prospectus explaining his plan and sent it to potential investors with a request for $100 from each. Keen’s believers, supplemented by a $2,000 loan from a supportive Aggie banker, provided the needed capital, and Keen headed to the studio.76 Acting as his own producer, Keen booked time at a local studio and enlisted his musical family, including Griffith and Lovett, to play on the recording. Having produced his own album, he now needed to find label help for distribution and, hopefully, a little promotion. He shopped the record and was happy to lease his debut to Philo, an imprint of folk, blues, and bluegrass under the independent Rounder Records.77 Released October 1, 1984, under the name Robert Earl Keen, Jr., No Kinda Dancer drew scant attention, although it did win Keen the Austin Chronicle’s Best Songwriter Award for 1984.78

Billboard Magazine, which offered one-sentence reviews of records released on independent labels, no matter how small, noted, “Engaging acoustic instrumentals and intelligent lyrics support Keen's impressive vocals.”79 Keen was initially pleased with this assessment of No Kinda Dancer, but he later realized that the phrase “intelligent lyrics” was simply a Nashville euphemism for a songwriter “going nowhere” and whose music would never be played on the radio.80

The album kicks off with the title track, which features a narrator recalling a night spent at the sort of Bohemian Texas smalltown dances Keen used to frequent on his family’s weekend trips to Columbus. Keen's date talks the singer into waltzing despite his protestations. His first recorded piece is about an outsider connecting to rural Texan traditions, a theme that runs through not only his work, but the work of those he would come to influence.81

The second track proved to be the most enduring and influential. One afternoon at the Church Street house Keen played an unfinished composition for Lovett, who was duly impressed. Sometime later, Lovett, despite only having heard the song once, played it back for Keen adding Lovett’s own final verse.82 “The Front Porch Song” has come to symbolize the halcyon days when Keen and Lovett developed the musical talents and sensibilities that transformed Texas music, but the song itself is actually a celebration of the remains of a more agrarian Texas that surrounded them.83 The track is acoustic, featuring only stringed instruments. A choppy, percussive rhythm guitar keeping time replaces drums while a stand-up bass follows the guitar through alternately descending and ascending chord changes. Paul Sweeney’s mandolin solos between verses add to the rustic charm. Even before the lyric begins, the song unmistakably evokes Texas’s past.

The first verse relates the porch to an “old bull” in the rural South Texas hamlet of Agua Dulce whose “work is never done.” Keen then turns his attention to the enchilada plate served in a pre-Depression grand hotel. The third verse takes the listener to a movie palace whose last feature was the 1962 film Giant.84 Here Keen makes a subtle connection to McMurtry’s Last Picture Show, whose young characters escape to the town’s movie theater for the privacy to make out with their girlfriends.85 The closing of the theater referred to in the novel’s title symbolizes the end of the characters’ innocence as well as the dying of a way of life.

Lovett’s verse introduces the Church Street house landlord, Jack Boyette, “a weathered gray-haired seventy years of Texas / Who’s doing all he can not to give into the city.” Boyette lets Keen slide on his rent in exchange for help with his cattle. In a Texas Monthly piece on great Texas songs, Lovett explained how Boyette “would walk right in, make himself at home. But Robert treated him like he belonged there, and he’d go help him move his cattle or build a fence. I admired that.”86

The song finishes by reprising the first verse, suggesting a conflation of the bull, the old rancher, and the young songwriters themselves with an aside. “I’ve known a whole lot of old bulls in my life and their work is never done.” Thirty years later, this early composition still holds a special place for the Texans. Keen humbly credits his friend. “The song didn’t breathe until Lyle got to work on it.”87 For Keen, the song is a connection to his college days where he forged his own identity through Texas’s rich musical tradition. “I suppose the porch does have a meaning of its own now. It’s our Walden Pond—it takes you back to a simpler place, to where you can just hang out and be yourself around friends.”88

To Keen’s musical descendants the porch on Church Street is a Garden of Eden, the birthplace of a new epoch in Texas music during a time of innocence. It represents the simpler mythological past both Keen and McMurtry imagined in their pursuit of their lost Texanness. The song, which has been profiled in Texas Monthly, holds a special place for Aggies. For Keen and Lovett to not only emerge from the smaller College Station but to so publicly embrace their Aggie identities stoked an unrivaled passion among A&M alumni for the two songwriters.

The rest of the album established themes Keen and those he inspired would address over the coming decades. His dark, incisive wit is on display in “Swervin’ in My Lane” and “The Armadillo Jackal,” the former with a descant written and sung by Nanci Griffith. The most idiosyncratic tune on the album is the gothic “Christabel,” a supernatural tale of an ageless succubus who seduces a passing motorist. The occult themes did not establish a trend in Keen or later artists’ work, but “Christabel” and “The Armadillo Jackal” do stand as Keen’s first two recorded cinematic narratives which transcend the standard boy and girl romantic formula. These story songs, with their vivid characters and relatively complicated plots, became, along with his darkly comic work, Keen’s trademarks.

No Kinda Dancer also established a major theme in what would come to be called Americana music, and it emphasized the most significant lyrical difference between the genre and its Nashville counterpart. Both Nashville and Americana music frequently focus on rural America and its denizens. Nashville music tends to celebrate contemporary rural America as a bastion of good values and idyllic living. Mainstream country songs often proclaim the virtues of smalltown life, implying or explicitly claiming it as superior to a more urban, modern lifestyle. Nadine Hubbs explores the lyrical content of Top 40 country in her study Rednecks, Queers, and Country Music, concluding, “country music is . . . the sound of working people, small-town America, and an idealized simpler time.”89 In the first half of the decade, hits championing rural life over the corrupt city consistently topped the country chart. In Dolly Parton’s “Tennessee Homesick Blues” (1984) the narrator flees New York City to eat grits and gravy before loading up the hounds and catching a coon with dad in the backwoods. Don Reid’s “Child of the Fifties” (1982) bemoans the new America filled with income taxes and TV reruns. John Anderson’s “Swingin’” (1983) rode a catchy chorus built around the singer’s southern drawl to number one. Hank Williams, Jr., an artist associated with the outlaw country movement, turned rural resentment into a cottage industry by the early 1980s. Singles such as the platinum hit “A Country Boy Can Survive” (1982) and “This Ain’t Dallas” (1984) stoked white rural resistance to an urban world perceived as increasingly alien.

Keen’s lyrics also frequently address rural themes, but their praise is almost universally limited to the agrarian past. He does not show contemporary rural life as desirable and certainly not as a lifestyle fit for aspiration. Keen clearly articulates these ideas on his debut. “No Kinda Dancer” does present a rural dance as a charming, quaint setting, but the narrator is an outsider, hence his insistence he lacks the skills to dance to the music. “Willie” features Keen contemplating “a print I got from grandma / a real West River cowgirl in her day.” While the western scene clearly fascinates Keen, he is just as clearly an outsider pondering a Texas heritage from which he feels separated. Keen also takes the opportunity to comment on the exploitation of his heritage. “And now the western feeling has become another sideshow / A selling out the bygone days gone by.”90

“Young Lover’s Waltz” tells a love story of “a boy called Caballo” wooing a girl at a dance featuring Bob Wills and the Texas Playboys. The presence of Wills both allows Keen to directly cite one of his major influences and fixes the setting in the first half of the 20th century. Interestingly, like Keen in the first track, the farm boy Caballo and his “blue girl” “weren’t much on dancing that old ballroom style,” although unlike Keen, the pair did not hesitate to try.91 “Death of Tail Fitzsimmons” is a rousing acoustic string band instrumental, which recalls an earlier epoch in Texas music even without lyrics. The instrumental, like all the album’s tracks, is recorded in a minimalist style. Due to the limits of the facilities and the budget, elaborate production effects were not an option. Even if they were, Keen’s stage act and musical sensibilities at the time suggest he would have chosen the bare, stripped-down sound the album features. Each of these songs presents McMurtry’s fading agrarian Texas past in nostalgic terms but keeps both Keen, as the narrator, and the listener at a distance in time. As much as Keen may admire and yearn for Texas’s past, he never confuses it with the present.

The ninth track on the album turns its attention to contemporary rural Texas. Keen has described “Rollin’ By” as “the kind of song [Lovett] would write.”92 Lovett liked the song enough to include it on Step Inside This House (1998), an album featuring Lovett covering his own influences. Keen’s vision of a “busted old town on the plains of West Texas” is bleak. The town has been reduced to a dry river, a closed drug store, an abandoned mission, and a closed down drive-in, a second nod to McMurtry’s Last Picture Show. Keen takes care to point out the “grave where the old cowboys lie,” an acknowledgement that the characters from the earlier songs have faded away. Keen does not belong in the town, having simply pulled into “the last filling station” off the highway where “semis roll through like stainless steel stallions.” Soon enough Keen, gazing on the ruins of the once mighty agrarian Texas past, is “back out on the highway goin’ hard, goin’ fast, goin’ by.”93

Keen’s lyrics in songs such as “Young Lover’s Waltz” and “Willie” distinguished themselves from mainstream country by being firmly rooted in the belief in McMurtry’s preindustrial utopia. For progressive country songwriters, this rural utopia was, at times, presented as a place to escape to in the present as seen in songs such as Michael Martin Murphey’s “Cosmic Cowboy Pt. 1” (1972) or Guy Clark’s “LA Freeway” (1972). Keen rejected the fantasy that an agrarian escape was a possibility. Contemporary rural life had little to offer college-educated young Texans on the verge of the twenty-first century.

From the beginning, Keen’s personality shone through. His songwriting and determination impressed Tracie Ferguson, who regularly booked the fledgling performer in the front room at Gruene Hall for singer-songwriter shows. One night in 1984, Ferguson brought a friend to hear Keen’s stories and songs at an Austin venue, Emma Jo’s.94 The friend, Kathleen Gray, was impressed with Keen’s wit. On December 10 of that year, Griffith performed for the nationally renowned Austin City Limits PBS television program. After the show, a group of musicians and friends retreated a few blocks south to the Texas Chili Parlor. Keen and Gray drank and chatted until last call. Keen asked Gray out and, for their first date, took her to ride the children’s train around Zilker Park. In June 1985, Gray moved in with Keen.95

After a half decade in Austin, Keen became restless. He had come to see the future “Live Music Capital of the World” as a “double edged-sword.”96 The luxury of being able to play music regularly and subsist sapped the will to find a broader audience. A chance meeting with Earle, where Earle imparted his “mañana” warning, encouraged Keen to try his hand in the higher risk-higher reward music market of Nashville, as Earle himself had.97

Keen moved to Nashville in 1985, followed shortly by Kathleen. The two married, and Kathleen thrived. She saw life with Robert Earl as an adventure, but the two struggled to support themselves. “I got great jobs but the hardest part was not having any money. . . . We didn’t pay any attention to it . . . we just had a great time together.”98 Keen quickly learned that while he had made money playing in Austin, Nashville was a different kind of scene. “I had to go audition to play three songs at songwriter night at the Bluebird Cafe. For free. And I was just totally indignant about it, like, ‘Are you kidding me?’”99 Keen was reduced to odd jobs to pay the bills including running Nashville’s legendary Hatch Show Print shop, digging ditches, temp work, and even landscaping country superstar Steve Wariner’s yard in a torrential downpour.100 For Keen, the low point came while he was digging a ditch and recalled his father had warned him this would be the result of pursuing music as a career.101

Musical stardom eluded Keen in Nashville. What had worked in Austin, Houston, and other Texas venues was poorly suited for Nashville. Austin and Nashville draw frequent comparisons and one illustrative feature is the nature of the live music scene audience. In Nashville, most artists are performing in the hopes that an influential figure in the recording industry will be impressed enough to champion the artist to a label.

Therefore, playing two or three songs during lunch to a handful of disinterested diners for no pay makes sense. The incentive is that one of the few people in the room might be an artist and repertoire person or an assistant to someone important who will talk up the artist. Performers attempt to showcase what might sound like a radio hit sung in a radio-friendly voice.

In Austin, particularly in the 1980s, a showcase of this sort would have been an absurd fantasy. In a market with virtually no label presence, the performer played almost exclusively at night in venues dependent on alcohol sales. The artist’s goal was to connect with as large an audience as possible and build a following. Performers gave little thought to winning over one fan that would unlock the key to stardom. Sets were long, and artists developed live shows designed to cultivate a sustainable party atmosphere that might encourage fans to buy some music, mention the artist to friends, and show up at the next show. Keen’s talents, as well as his evolution to fit the Austin scene, made him a poor candidate for Nashville stardom.

Even Keen’s successes in Nashville turned to failure. When a Waylon Jennings-funded foundation awarded Keen free studio time, the critique was devastating. “They couldn’t believe somebody would even submit this as a song. There’s no hook,” Keen recalled to Jan Reid.102 Keen’s songwriting had won over small rooms in Austin and his future wife, but Nashville record labels were interested in hit radio songs. “I was trying to write what I thought were hit songs, and they were terrible. I'd demo them, and pitch them, and I knew they were terrible.”103 Keen’s dream of finding his place in country music was unraveling.104 His frustration was complicated by the success of his friends.

By the early 1980s, Tony Brown had worked his way up to producing records for MCA in Nashville. His musical bona fides include playing keyboards for Elvis Presley and Emmylou Harris’s Hot Band.105 Harris first gained wide attention for her work with Gram Parsons on 1974’s Grievous Angel. Released shortly after Parsons’s death from a drug overdose, the album earned Harris her own recording contract, which she parlayed into eight Top-10 country albums between 1974 and 1981. She was widely admired for her eclectic material and country rock roots, which gained her significant adoration in progressive and alternative country circles.106 As a member of her Hot Band, Brown became convinced there was an audience for a more thoughtful, less pop-oriented country sound. As a producer, Brown determined to make this vision a reality.107

Dubbed the class of ’86, Brown’s discoveries challenged mainstream country music’s status quo. Under Brown’s production, Texans Earle, Griffith, Lovett, and fellow Hot Band alum Rodney Crowell each charted hit albums over the next two years. Joined by other artists such as Ohioan Dwight Yoakam, who revived the upbeat rock-infused Bakersfield sound of Buck Owens, and North Carolina new traditionalist Randy Travis, Brown’s roster appeared to mark a dramatic broadening of sonic possibilities in country music’s formulaic capital city. In the end, commercial country music proved too resistant to Brown’s vision to change significantly, but the artists he helped launch would each go on to successful careers and become important foundations for offshoots of country music such as alternative country, Americana, and Texas Country.108 Through Harris and Crowell, Brown had become acquainted with the circle of Texas ex-pats who spent their free hours at Guy and Susanna Clark’s Nashville home. Brown successfully mined Clark’s social circle to produce what appeared, at the time, to be a country music revolution.109

Crowell was already an established artist when Brown produce Diamonds and Dirt (1987), Crowell’s fifth release. Unlike Crowell’s earlier efforts, Diamonds and Dirt established Crowell as a superstar, sending each of the five singles to number one on the country charts and earning a gold record for the album. Among the chart toppers was “She’s Crazy for Leaving,” which Crowell co-wrote with his mentor Clark, the last of Clark’s three number-one songwriting credits. Crowell and Brown’s collaboration presented a more mainstream sound than Earle’s, Griffith’s, or Lovett’s efforts.110

Earle’s 1986 MCA rock-inflected debut Guitar Town shot to the top of the country charts. It still regularly appears on the Rolling Stone Top 500 albums list. Earle followed with a string of successful albums combining his love of country, bluegrass, and metal that have made him an oft-cited influence among songwriters and artists seeking to create music to challenge mainstream country.111

Griffith had released four independent albums before working with Brown at MCA. These early efforts earned Griffith songwriting credits on major stars’ albums, including a cut on Dolly Parton’s Real Love (1985). Two of Griffith’s songs from Last of the True Believers (1986) charted for Kathy Mattea over the next year with “Love at the Five and Dime” reaching number three and “Goin’ Gone” topping the country chart in 1987. These successes established Griffith as a songwriter and earned her a major label deal. In 1987, Griffith’s Lone Star State of Mind peaked at number 23 on the country charts with the title track cracking the Top 40. The final track on the first side is Griffith’s version of Keen’s “Sing One for Sister.” The next year Griffith covered Keen’s “I Would Change My Life” on Little Love Affairs (1988). Griffith’s covers of her friend’s songs are indicative of other artists’ respect for Keen as a writer.112

Keen’s closest musical companion took a circuitous path to national stardom. Lovett, whose confidence had inspired Keen, had stayed in college seven years because he preferred to describe himself as a college student rather than a struggling musician. Tired of playing the same handful of clubs around Texas, Lovett accepted an offer from Billy Williams, a musician he met while playing in Luxembourg. Travelling to Williams’s base of Phoenix, Lovett used Williams’s band to record a demo cassette. In 1984, Lovett abandoned the blues rock-filled bars of Texas to try his luck in Nashville. While shopping the cassette around town, Lovett made a point to drop one at Clark’s publishing company with a note explaining his admiration for the Texas songwriter. Amazingly, the tape made its way to Clark. Even more amazingly, Clark actually took the time to listen. Clark was remarkable for his willingness to tout unknown songwriters such as Earle and Crowell, and he added Lovett to the list despite having never met him. Clark explained, “I was making everyone listen to it. I was just obsessed.” When the two finally met in person, Clark remembered, “I took one look at him and pegged him for a French blues singer. I went on and sat down and then finally lights and bells went off. That’s the guy who left me all those incredible songs.”113

Clark’s boosterism landed Lovett a publishing deal and the chance to make a record at MCA with Brown. Lyle Lovett (1986) found both critical and commercial success. Hitting number 16 on the country chart, the Nashville establishment embraced the album’s quirky songwriting and its jazz- and rock-informed country sounds. The album also features Lovett’s slow, reflective version of “The Front Porch Song,” another major label songwriting credit for Keen. As Lovett’s star rose with an even more well-received follow up, Pontiac (1987), Keen found himself relegated to Lovett’s entourage. Keen struggled with being both happy for his friends and also feeling left behind.114 The differences between Austin and Nashville hurt him. In Austin, musicians had supported each other and worked together, while in Nashville, “everybody went off on their own, and it was a real-life lesson."115 Aside from Keen’s “intelligent lyrics,” which one A&R person described as “Jerry Jeff, Billy Joe Shaver, same old shit,” Keen’s voice was found wanting.116 Critics frequently described Keen's baritone as flat and nasal. Even more problematic for Nashville labels, his “voice can roam so far off key that whiskey jiggers rattle.”117 When asked who the next big thing to come out of Texas would be in the early 1980s, Kerrville Folk Festival founder Rod Kennedy singled out Keen, despite Lovett’s and Griffith’s recent major label signings, but Keen found himself left out of Nashville’s Class of 1986.118

In January of 1987, Keen’s car broke down in Missouri after a show in Kansas. After spending the last of their money to get the car fixed, the Keens arrived in Nashville to find thieves had raided their apartment. While freezing on the roadside in Missouri, Keen had watched as Earle’s tour bus zoomed by. “It seemed like an omen, because Steve was the guy who talked me into going to Nashville in the first place!” Four days later, the Keens left Tennessee, an episode Keen later put in verse sentimentally in “Leaving Tennessee” and comically in “Then Came Lo Mein.” Keen’s failure in Nashville, particularly in light of his colleagues’ success, left him bitter, depressed, and seriously considering giving up his musical dreams.119 Despite his apparent failure, Keen left Music City with crucial ingredients of his future success and the foundation of the legend Texas fans constructed around him. Keen had signed a publishing deal with MCA Nashville that supplemented his income. Perhaps more importantly, he had impressed booking agent Keith Case enough to be signed to Case’s agency. Case booked Clark, Van Zandt, and other singer-songwriter acts into intimate listening rooms and made Keen a staple of that circuit.120

Ironically, Keen’s failure to find a permanent place in Nashville is part of what made him so influential to a rising generation of Texans. While Clark, Van Zandt, Lovett, and Earle were all considered major influences, they lacked the immediacy of Keen to fans in Texas. Younger fans viewed the progressive country era as a rejection of the music and values Nashville represented. Despite the fact that major labels had backed virtually every recognizable name in the earlier scene, fans viewed progressive country as a homegrown Texan antidote to the more commercial Nashville sound.121 Central to the myth of Willie Nelson is his rejection of a successful songwriting career in Nashville in favor of making the music he wanted in Austin.122 Despite the fact Nelson left by choice and Keen left out of desperation, the two artists’ stories mirrored each other and lent credence to the notion that escaping Music City for the Lone Star State freed each to make a more authentic brand of music specifically tailored for Texans.

Keen’s relative anonymity, as compared to his more successful cohorts in the Class of 1986, propelled Keen to regional superstardom in a simpler way as well. While Keen’s major label colleagues toured widely, playing high-dollar venues before hushed crowds, Keen was forced to play frequently around Texas in a more diverse set of venues at much lower ticket prices. This material reality meant Keen’s growing college-aged fan base could see Keen often at affordable prices, greatly increasing the fans’ sense of ownership in Keen. Lovett, Earle, and others, regularly touring internationally, played any given market in Texas infrequently and were able to charge significantly more when they did. Consequently, even young fans who enjoyed these bigger stars’ music were unlikely to get to see these national acts. This immediacy was a necessary element in forming a neo-progressive country Texan identity for a postmodern generation who demanded a more personalized commodity.123

The Keens retreated to the Texas Hill Country town of Bandera, where Kathleen’s parents lived. The Grays helped the couple buy a dilapidated vacant home and gave Kathleen a job in a nursing home they owned.124 Keen worked construction and battled depression over the supposed end of his music career. His new surroundings did not help. “I had never really been to Bandera, and came down here on a day when it was cold, 30-mile-per-hour wind, all blue sky, and no sun at all. There were about two cars parked on all of Main Street and tin cans bumping down the middle of the road. I thought, ‘I have come to the end of my life.’” Soon, freed from the need to fit into the Nashville mold, Keen began to write new songs.125 After five months of “sitting around with my head in my hands,” Gruene Hall’s Mary Jane Nalley called and offered Keen a regular spot in the venerable dance hall’s front room. Keen equivocated, reasoning, “‘I didn’t want to overexpose myself. Maybe I’ll play once.’ It was possibly the stupidest thing I have ever said.” Coming to his senses, Keen called back and agreed to play twice a week through the summer of 1987. Joined by his fiddle-playing childhood friend Duckworth, Keen resurrected his career in the oldest continually operated dance hall in Texas.126

By 1988, Case had begun booking Keen not only around Texas but also around the country, including shows opening for Guy Clark.127 Soon Keen felt his live show was strong enough to record for his second album. After Rounder Records countered Keen’s paltry request of $9,500 with an offer of $3,000 to produce the record, Keen turned to Sugar Hill for his second release.128 Founded in 1980, North Carolina-based Sugar Hill Records specialized in bluegrass and folk and, like Keen himself, became a pioneer in the Americana genre in the 1990s.129 Having recently released Van Zandt’s At My Window (1987) and Clark’s Old Friends (1988), the label was a a natural fit for Keen.130

Keen chose the Sons of Hermann Hall in Dallas, a 200-seat listening room, as the venue for The Live Album (1988). The album features only acoustic stringed instruments including Keen’s guitar, Roy Huskey Jr.’s upright bass, and Johnathan Yadkin switching between fiddle, mandolin, and guitar. Billboard Magazine found Keen “droll and immensely personable” on his sophomore effort.131 The Houston Chronicle praised the release, observing that the album “showcases Keen's sensitive songwriting, his hilarious wit and his easygoing approach to performing.”132 Writing in the Austin American-Statesman, Casey Monahan, who would go on to head the Texas Music Office from 1991 to 2015, appreciated Keen’s “lyrical web . . . thick and gooey . . . like the enchiladas he sings about in ‘This Old Porch.’”133 The reverence for and disconnect with Texas rural past is even more present on The Live Album than on No Kinda Dancer.134 Keen begins the album with “I Wanna Know,” a track co-written with Fred Koller. In the lyric, Keen implores an elder to tell him about the past. The chorus makes plain Keen’s fascination with an earlier time. Keen asks an old-timer to “share some memories” to “take me back to a time I’ve never seen.” In the chorus he questions whether the new friend’s father owned an automobile or a two-horse carriage, if he rode a railroad, and what he thought the first time he saw a plane.135 From the first track of the album Keen makes clear that while he is interested in an earlier time, he does not pretend to be a part of it himself, highlighting the difference between his lyrics and Top 40 country, which tends to be written from the point of view of rural Americans.

Artists record live albums for two reasons. The first is live recordings tend to be cheaper than studio efforts. The second is an attempt to capture the energy and excitement of a performer’s live show.136 Keen’s second track on The Live Album established the artist’s on-stage persona that made his live shows legendary. Storytelling on concert albums is not uncommon, but typically it occurs before the song, allowing fans to hear the song itself as often as they like without hearing the story attached to it repeatedly. On the live version of “The Front Porch Song,” Keen engages in an extended retelling of the events surrounding the song’s composition between the second and third verses, as was his regular practice. The laughter of the crowd establishes the atmosphere of Keen’s live show and the story itself connects him to Lovett, who was a major star at the time, and Texas A&M University, whose students and alumni formed a significant portion of Keen’s early fan base.137

The album also includes stories before “Copenhagen,” a tongue-in-cheek ode to snuff, and in the middle of “The Bluegrass Widow.”138 The latter, a song made entirely from stringing the names of classic bluegrass songs together, is interrupted by a story of the Front Porch Boys finishing second in a bluegrass festival in Crockett. Keen claims, “The other two bands finished first and third respectively.”139 Songs such as these, with their comic anecdotes filled with regional references, helped make Keen a favorite among college-aged fans in the years to come while the album’s more serious material, most notably “I’ll Go on Downtown,” gained him admiration in folk circles.

The spring of 1989 was a prolific period for Keen. Aside from releasing his second record, he was one of three founding partners in Austin-based Watermelon Records, and appeared for the first time, albeit as one of many in a song swap, on Austin City Limits.140 Capitalizing on this momentum on one of his regular trips to Nashville, Keen spent two days recording a studio follow-up to The Live Album. After sitting on the completed album for five months, Sugar Hill released West Textures on November 10, 1989. Keen’s third album was the first to receive significant attention in the local press, earning four stars and being praised as “a testament to the songwriter’s honesty and eloquence.” Keen’s voice, too ordinary for Nashville, was recast as “undeniably human.”141 Keen’s warbling baritone now enhanced his “honest, eloquent” lyrics because, as Talking Heads’ David Byrne once explained, “The better a singer’s voice, the harder it is to believe what they’re saying.”142

In Monahan’s interview with Keen about the new record, both the journalist and the artist discussed the album’s potential success in terms of getting Nashville artists to cover the tracks. Two ballads, “Leaving Tennessee” and “Love’s a Word I Never Throw Around,” were considered strong candidates. Keen’s latest, Monahan claimed, placed the artist in the rarified company of esteemed songwriters such as Clark, Van Zandt, and Butch Hancock. Keen was hopeful his new writing would help him shred his “frivolous” image and be taken “seriously” by Nashville as a songwriter. In the 1980s and for much of the 1990s, success for writers such as Clark and Van Zandt meant publishing royalties earned from appearing on major label records. These artists did not draw well and had little chance of radio exposure performing their own songs. Keen and Monahan’s conversation makes it clear West Textures was not expected to build a following for Keen, but rather to raise his profile in the country music business. Neither Statesman piece even mentioned the album’s second track, a modern-day gunfighter ballad called “The Road Goes on Forever.”143

“The Road Goes on Forever” came to be Keen’s most widely known and enthusiastically received song as well as “quite possibly the best-known anthem in Texas music since Jerry Jeff Walker introduced both Gary P. Nunn’s ‘London Homesick Blues’ and Ray Wylie Hubbard’s ‘Up Against the Wall (Redneck Mother).’”144 Keen’s magnum opus tells the tale of Sherry, a cocktail waitress who falls for a small time drug dealer, flees to Miami, and murders a cop to save her new man.145 Her beau, Sonny, takes the fall, and we last see Sherry driving down Main Street in a new Mercedes. The lyric’s eight verses, each ending with, “the road goes on forever and the party never ends,” play out like a “little movie,” what Jan Reid called “an Elmore Leonard novel boiled down into a five-minute essence of hard luck, love and betrayal.”146

According to Keen, the song was less a result of inspiration than desperation. Sugar Hill producer Jim Rooney felt the album’s original batch of songs lacked an “anchor” track and suggested Keen cancel the session. Not wanting to lose the studio time, Keen spent that evening working up the song.147 “I just started with this woman that worked with Kathleen and she was with this guy that was real rough. No matter what good luck landed on them, they would manage to screw it all up.”148 Rooney was impressed enough with Keen’s “hapless, updated Bonnie and Clyde,” and the recording session continued.149 Keen claimed his interest lies primarily in narrative songs such as “The Road Goes on Forever.”150 His home state inspired these musical stories. “The sense of place here, for me, has always been about openness—not only the landscape, but the people. It always seems a little more edgy, a little more frontier-like.”151 Keen’s narratives played out like “little four-minute movies” and were rich with subtext, characterization, and implied endings.152

After three albums and a decade of playing music professionally, Keen had established himself as a rising star in the folk scene, routinely selling out small listening rooms such as the University of Texas’s 150-seat Cactus Café.153 Nashville-based booking agent Case sent Keen across America, and even to Europe, in 1990, and again in 1991, opening for Guy Clark and Townes Van Zandt. These shows thrilled Keen because they gave him an opportunity to watch two of his idols, the audiences “would sit there completely quiet” for the entire show, and he would sell $700 to $800 a night in merchandise.154

Clark, a tireless mentor of rising songwriters, got along well with Keen, but Van Zandt “was just aloof.” In fact, one reason Case put Keen on the tour was Van Zandt’s inability to rent a car due to the legendary folk singer’s itinerant, addiction-plagued lifestyle. As he had for his sister two decades earlier, Keen served as Van Zandt’s driver, but the passenger did not socialize and impressed Keen with his ability to sit perfectly still for long periods of time. Still Keen was grateful to see Van Zandt “in the last great period when he was relatively sober” before the composer of “Pancho and Lefty” and “If I Needed You” succumbed to health problems stemming from his various addictions on New Year’s Day, 1997.155

By 1991, in San Antonio, near his Bandera home, Keen had begun to consistently sell out the small venues he headlined thanks largely to airplay on Hill Country radio stations KRIO and KFAN: Texas Rebel Radio. The San Antonio Express-News even declared Keen “the Guy Clark of the 90s.”156 Keen pointed to this period as a turning point in his career. A member of Case’s staff, Denise Stiff, dreamed up a “World Tour of San Antonio” for Keen, which consisted of five shows in five different venues around the Alamo City, including Gruene Hall and Floore’s Country Store. Keen recalled the first gig of the series at El Patio Mexican Restaurant on October 16, 1991.157 “I could barely get to the front door, and I asked some guy at the back of the line ‘What’s the deal?’ And the guy said ‘This guy Robert Earl Keen is going to play.’ So I said, ‘You’ve got to be kidding me.’ There were at least 1500 people there. And it was truly the power of radio.”158

In the singer-songwriter circle Keen inhabited, his peers had also benefited from radio play, but from other artists’ covers of their work. Clark’s claim to fame largely rested on two Jerry Jeff Walker covers, “Desperados Waiting for a Train” and “LA Freeway.” Van Zandt’s most famous compositions were “If I Needed You,” a 1981 hit for Don Williams and Emmylou Harris, and “Pancho and Lefty,” which topped the country chart for Willie Nelson and Merle Haggard in 1983. Now it was Keen’s turn to play songsmith for more well-known artists. Keen attended a song swap in 1991 featuring John Hiatt, Guy Clark, Lyle Lovett, and Joe Ely. Lovett invited Keen onstage to play a song. Ely recalled, “I had never met him before, but he played ‘The Road Goes on Forever,’ and as soon as he finished it, I said, ‘I’m recording that. I don’t care what you say.’ Then he played me another one, ‘Whenever Kindness Fails,’ and I said, ‘I’ve got to do that one, too!’” True to his word, both tracks appear on Ely’s 1992 MCA release Love and Danger.159 In 1995, the country supergroup the Highwaymen made Keen’s “The Road Goes on Forever” the title track of their second album, allowing Keen to hear his early heroes Willie Nelson, Johnny Cash, Waylon Jennings, and Kris Kristofferson cover his composition.

While Keen’s early 1990s rise in popularity in his home state left a new generation of Texas Country musicians dreaming about being Keen, Keen was dreaming about being something else. Rod Bleetstein had begun his radio career at progressive country station KHIP in Monterey Bay, California, in 1985. Soon after he joined, he and the station embraced Nashville’s class of 1986, regularly playing Keen’s confederates Lovett, Griffith, Earle, and other genre-challenging country artists. Disappointed that mainstream Nashville music weathered the challenge, Bleetstein continued to promote the sort of outside-the-box country he loved.160 In the summer of 1994, after working with Keen for a year, Bleetstein found himself at a party with staff from the Gavin Report, a music industry trade magazine that published a wide variety of subgenre charts. Bleetstein pointed to the success of alternative rock as a format and suggested there was room to market alternative country. Excited to learn many at Gavin held similar musical tastes, Bleetstein went home that night and outlined a proposal for what would become the Americana chart.161

Bleetstein and Gavin premiered the chart, a crucial step in defining a set of artists as a genre, on January 20, 1995. The issue’s cover features Keen, prominently placed among Joe Ely, Lucinda Williams, Emmylou Harris, and six, nestled between his old friends Griffith at number two and Lovett at number seven. Bleetstein’s articles explained Americana music would appeal to “disenfranchised country listeners” the same way grunge had recently won over alienated rock fans. Americana would also include classic country legends such as Johnny Cash, George Jones, Waylon Jennings, and Merle Haggard. “It’s steel guitars, mandolins, and acoustics rather than synthesizer and line dance mixes,” Bleetstein declared. Keen, the first featured artist to be labelled Americana, predicted, “It’s gonna blow the dust off all the diamonds in the rough.”162 Keen was delighted. “Finally, after years without a label for my music, I had a flag to rally around. . . . Lyrically, it’s tougher, funnier, and more surreal, with narrative endings that would never pass muster in a focus group.” After years of struggling to explain his style of music, he finally had an answer. “When a stranger asks what kind of music I play, I look them square in the eye and say, ‘I play Americana.’”163

As the modernist musical consensus gave way to postmodern pluralism, the music charts reflected this change. In 1976, the summer Keen met Lovett and began seriously considering a career in music, Billboard Magazine, the industry standard in song and album rankings, featured charts covering just five genres of American music: jazz, soul, country, easy listening, and rock.164 Less than two decades later in 1995, the year Gavin premiered the Americana chart, Billboard recognized fifteen different musical styles.165

Genres are constructs of radio stations, promoters, and record labels. Artists do not need defined genres to create music; the music business needs genres to sell music. The dramatic increase in the number of genres acknowledged by the music industry suggests radio stations and record labels had come to recognize the diversity of musical tastes in the US market and were attempting to cater to what were once seen as niche musical styles. Through the act of defining and formally recognizing these genres, the national music industry was formally acknowledging what Texas Country fans had been embracing for years: a new generation of fans desired a more personalized musical experience. Both Texas Country and Americana fans had made a conscious decision to elevate a relatively obscure musical subgenre above nationwide, mainstream artists. By making this choice, fans created an identity for themselves, which they defined in opposition to the acceptance of a broad musical consensus. The limited commercial appeal of their chosen music was not seen as a failure but an authenticity-generating necessity. As the growth in charts shows, this phenomenon was not limited to Americana, but a growing number of musical genres and subgenres were rapidly creating in music the pluralism associated with postmodernism.

Keen spent the 1990s establishing himself as a major figure in the rising Americana movement while simultaneously inspiring artists such as Jack Ingram, Cory Morrow, Pat Green, and Randy Rogers to create the musical genre known as Texas Country.166 He assembled a respected touring band and become one of the state’s top live draws. In 1997 Keen’s role in forging a new music genre landed him a contract with Arista’s Austin imprint. Keen had spent years trying to find a niche for his brand of Texas-based, roots-inspired “intelligent lyrics.” In the end, he, and his musical peers, created their own. One night at the Executive Surf Club in 1998 I asked Robert how he categorized his music. He flashed his mischievous grin and gave me a line I had heard him use from the stage several times. “It’s music for people who don’t like country music.” Keen’s music is not in opposition to country music or rural America; it simply views this world through a slightly different lens. This shift in perspective opened up the music that inspired Keen to an entirely new audience and allowed him to overcome years of frustration to become one of the most influential and beloved Texas performers of his generation.

Notes

1. Christian Wallace, “Behind the Scenes at Robert Earl Keen’s Final Show,” Texas Monthly, December 2022.

2. Wallace, “Behind the Scenes.”

3. Peter Blackstock, “Robert Earl Keen packs Cosmic Coffee for a surprise final Austin show,” Austin American-Statesman, August 31, 2022.

4. Christian Wallace, “Bus Fires, Voodoo Candles, and Rodeo Legends: Inside Robert Earl Keen’s Epic Final Tour,” Texas Monthly, December 2022.

5. Larry McMurtry, In a Narrow Grave: Essays on Texas (New York City: Dial Press, 1968), xiii.

6. McMurtry, In a Narrow Grave, 27-8.

7. Jason Mellard, Progressive Country: How the 1970s Transformed the Texan in Popular Culture (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2013), 6.

8. Skip Hollandsworth, “With Envy,” Texas Monthly, June 2002, 84-87, 119-121.

9. Jan Reid, “The Cult of Keen,” Texas Monthly, April 1996, 84-88.

10. Chris Lane, “The Changing Face of Houston: Sharpstown Then and Now,” Houston Press, September 15, 2014.

11. Nick Forster, “Episode #1643 Robert Earl Keen/John Fullbright,” eTown.org, October 26, 2016, 59:01.

12. Jan Reid, “The Cult of Keen.”

13. Shermakaye Basse, “TH Moment: Robert Earl Keen,” Texas Highways, June 2009, .

14. Skanse, "Robert Earl Keen: A Man Apart,” Lone Star Music, September/October 2011.

15. Robert Earl Keen, Jr., “The Bluegrass Widow,” No Kinda Dancer, Philo, 1988, LP.

16. Michael Hall, “On the Porch with Robert and Lyle,” Texas Monthly, July 2015.

17. Skanse, “A Man Apart.”

18. Matt Kemp, “Robert Earl Keen: Confessions of a Front Porch Picker,” Acoustic Guitar, January 15, 2016.

19. Bill C. Malone and Jocelyn R. Neal, Country Music U.S.A. (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2010), 386-7.

20. Michael Coyle and Jon Dolan, “Modelling Authenticity,” in Reading Rock & Roll: Authenticity, Appropriation, Aesthetics, ed. Kevin J.H. Dettmar and William Richey (New York: Columbia University Press), 30.

21. Jefferson Cowie, Stayin’ Alive: The 1970s and the Last Days of the Working Class (New York: The New Press, 2012), 182-187.

22. Jan Reid, The Improbable Rise of Redneck Rock (Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 2004), 14.

23. McMurtry, In a Narrow Grave, xiv.

24. Peter Sagal, “Not My Job: Singer Robert Earl Keen Gets Quizzed On Cats,” National Public Radio, March 7, 2015.

25. Forster, “Episode #1643 Robert Earl Keen.”

26. Skanse, “A Man Apart;” Forster, “Episode #1643 Robert Earl Keen.”

27. Benjamin Filene, Romancing the Folk: Public Memory and American Roots Music (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2000), 47-75.

28. Tamara Saviano, Without Getting Killed or Caught: The Life and Music of Guy Clark (College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 2016), 69.

29. Saviano, Without Getting Killed or Caught, 72-77.

30. Saviano, Without Getting Killed or Caught, 72-77.

31. Jan Reid, “Lyle Lovett and Robert Earl Keen: Cosmic Aggies,” in Pickers & Poets: The Ruthlessly Poetic Singer-Songwriters from Texas, ed. Craig Clifton and Craig Hillis (College Station, TX: Texas A&M University Press, 2016), 167.

32. Jan Reid, Improbable Rise, 13.

33. Travis D. Stimeling, Cosmic Cowboys and New Hicks: The Countercultural Sounds of Austin’s Progressive Country Music Scene (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011), 4.

34. Skanse, “A Man Apart.”

35. Danny Garrett, Weird Yet Strange: Notes from an Austin Music Artist (Fort Worth: TCU Press, 2015), 128.

36. Robert Earl Keen, “The Road Intro,” No. 2 Live Dinner, Sugar Hill, 1996, CD.

37. Doug Freeman, “Robert Earl Keen: Inside REK’s inner sanctum, the ‘Scriptorium,’” Austin Chronicle, January 30, 2015.

38. Kemp, “Confessions of a Front Porch Picker.”

39. Skanse, “A Man Apart.”

40. “At Home in Texas—Robert Earl & Kathleen Keen,” Comanche Trace (blog), April 1, 2010.

41. “At Home in Texas.”

42. Gray, “One More Image.”

43. “At Home in Texas.”

44. Kemp, “Confessions of a Front Porch Picker.”

45. Skanse, “A Man Apart.”

46. Andy Langer, “A Bit of Banter Between Robert Earl Keen and Lyle Lovett,” Texas Monthly, May 28, 2013.

47. Kemp, “Confessions of a Front Porch Picker.”

48. Freeman, “Inside REK’s inner sanctum.”

49. “Songs from the Year 1976,” March 29, 2023.

50. “Still on the Road: 1975 Rolling Thunder Revue,” June 22, 2019.

51. Paul Grein, “Chart Watch Extra: Where ‘Thriller’ Ranks,” Chart Watch, November 20, 2012.

52. Legs McNeil and Gillian McCain, Please Kill Me: The Uncensored Oral History of Punk (New York: Grove Press, 1996).

53. Jeff Purcell, “All Hands on Deck,” The Guardian, February 26, 2009.

54. Peter Hook, Unknown Pleasures: Inside New Order (New York: HarperCollins, 2013), 30-35.

55. Reid, “Cult of Keen.”

56. “At Home in Texas.”

57. Gray, “One More Image.”

58. Jim King, “Robert Earl Keen and Jim King of the Road,” YouTube Video, 5:25, September 27, 2012, accessed February 1, 2017.

59. Skanse, “A Man Apart.”

60. Michael Kilian, in discussion with the author, Austin, Texas, February 21, 2017.

61. Brian Zintgraff, in discussion with the author, San Antonio, Texas, February 20, 2017.

62. “At Home in Texas.”

63. Mellard, Progressive Country, 183-90.

64. Barry Shank, Dissonant Identities: The Rock’n’Roll Scene in Austin, Texas (Hanover: Wesleyan University Press, 1994), 102.

65. Skanse, “A Man Apart.”

66. Freeman, “Inside REK’s inner sanctum.”

67. Don McLeese, “Robert Earl Keen—Straight Outta Bandera,” No Depression, October 31, 1998.

68. McLeese, “Straight Outta Bandera.”

69. Jim King, “Robert Earl Keen and Jim King of the Road.”

70. E. R. Barefield, “The Kerrville Folk Festival and the Path to Kerr-Vision,” The Journal of Texas Music History 11, no. 1 (2011): 22-38.

71. Forster, “Episode #1643 Robert Earl Keen.”