JTMH Volume 24 | The Acosta Music Company

The Acosta Music Company: The Mexican Immigrant Luthiers Who Helped Shape the Tejano Sound

Todd Cambio

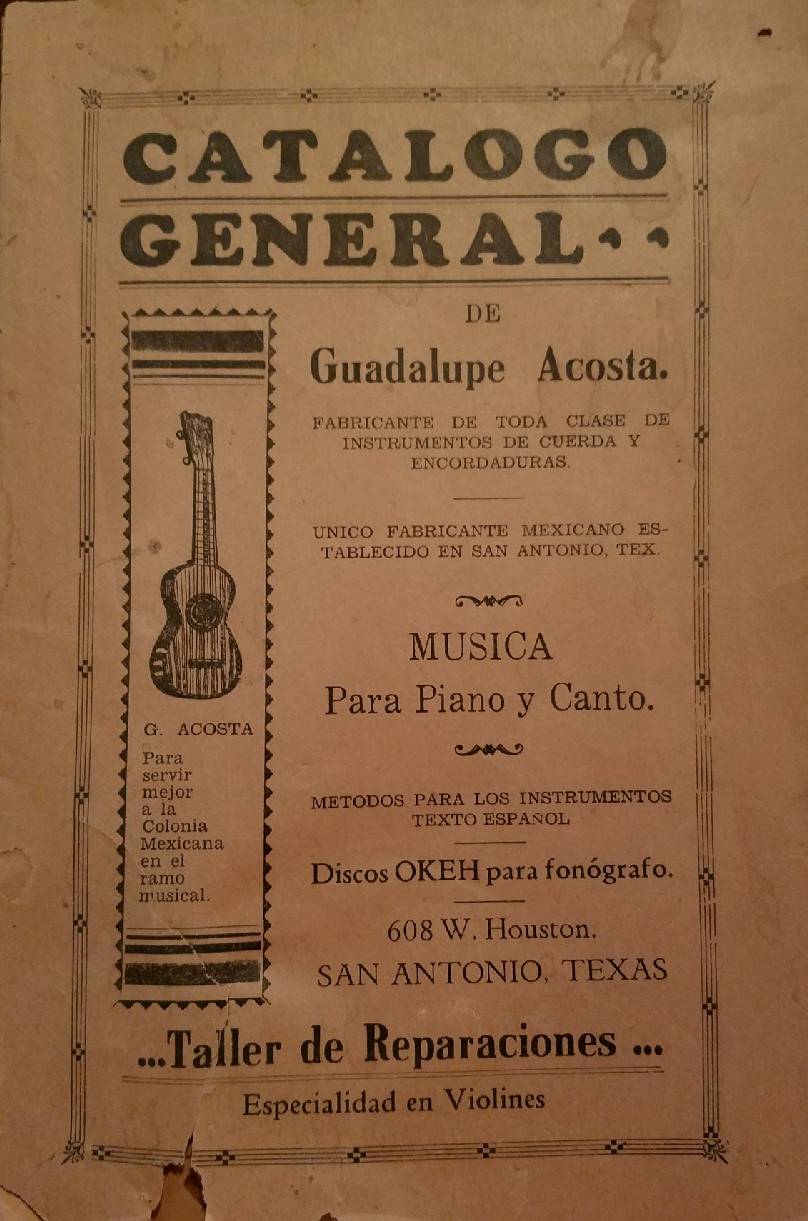

In 1920, Guadalupe Acosta opened a music store in San Antonio, Texas, with the motto “Para servir mejor a la Colonia Mexicana en el ramo musical” (To better serve the Mexican community in the musical realm).

Acosta’s shop was one of the first in Texas to manufacture instruments like bajo sextos, guitarra dobles, guitarra séptimas, mandolins, and bandolones. He also made strings for those instruments, which he shipped all over the United States. Acosta also sold accessories, sheet music, songbooks, and records at his store. He and his son Luis worked as talent scouts for early record companies, like Columbia and Vocalion, that were looking for Mexican musicians in and around San Antonio. Acosta made instruments for many of those musicians, including Lydia Mendoza, Santiago Almeda, and blues and jazz pioneer Lonnie Johnson. The influence that the Acosta family had on the distribution and dissemination of early Tejano music cannot be overstated.

Guadalupe Acosta was born in Lagos de Moreno, Jalisco, on December 12, 1885. He was the youngest of eight children and had been trained as a guitar maker by his father, Domingo Acosta. Domingo Acosta was described by his grandson Miguel Acosta as “an Indian” who was married to a Spanish woman, Vincenta Silva. Domingo was the first person in the Acosta family to learn lutherie, the trade of manufacturing stringed instruments. Domingo Acosta built instruments in a shop that was located on his property, behind his house, in Lagos de Moreno. He was a talented luthier who exhibited a cello he had made in Mexico City. In addition to cellos and guitars, which he made in the traditional Spanish style, Domingo also made a number of traditional, uniquely Mexican instruments like the bajo sexto, guitarra séptima, Mexican harps, and bandolón.1

It was common practice for the Spanish to teach different trades to the indigenous population of Mexico in their conquest of the territory. In 1538 the bishop Vasco de Quiroga chose trades for each of the villages in the state of Michoacán and set up vocational schools. The town of Paracho, which in the Tarascan language means “home of instrument makers,”2 was assigned the guitar, with the Spanish variety serving as its model.

Guitar making was not exclusive to Paracho. In 1568 an ordinance was passed in Mexico City stating the following:

No carpenter, no engraver, no joiner, no maker of musical instruments shall set up shop in this city or in its environs without passing the prescribed examination. . . . An instrument maker by examination must show that he knows how to construct the organ (without pedals), the spinet, the monochord, the lute, the various different kinds of viol and the harp: and he must know not only how to make these instruments but also must be able to demonstrate the correct method used in playing them.

The examination shall be given under the supervision of the alcade, and of the municipal supervisor of construction. A fine of ten pesos shall be levied against anyone who opens a shop without first passing his examination. . . . Special care shall be exercised to make sure that no one presumes to make the various classes of viols unless he knows how to attend to the most minute details and can fashion a truly presentable instrument. . . . Every four months an official examiner shall overlook the stock of instruments carried by an instrument maker, and shall confiscate all of those which are of faulty workmanship.3

These stringent guidelines were put in place to ensure that quality instruments could be provided to the market in Mexico. By 1598 the indigenous population of Mexico was making instruments that were of a similar quality to those produced in Spain. While the vihuela was considered the instrument of the elite, the guitar was the instrument of the common people. The guitar was not deemed acceptable to be played in church, so it took to the streets and was often played by women.4

Domingo taught his trade to his sons, including Guadalupe. He died when Guadalupe was 14 years old (around 1900), and his eldest son Bonifacio inherited his house and business. Guadalupe continued to work for his brother building instruments. He also worked as a carpenter, building furniture and houses, and as a musician. He was an excellent musician who played the bajo sexto and double bass in a variety of groups. According to his son Luis, Guadalupe played in saloons and brothels in a band that consisted of bajo sexto, trumpet, drums, and double bass. The band played a mixture of waltzes, marches, and paso dobles and sang corridos that reflected the events of the day. Guadalupe also played in the town square and for serenades or “gallos.” At the beginning of the Mexican Revolution he played in a band for Pancho Villa.5

Guadalupe’s primary instrument was the bajo sexto, a 12-string bass guitar which is equipped with six pairs, or courses, of strings that are tuned entirely in fourths. From high to low the strings are tuned F-C-G-D-A-E. The first three courses are unison courses, while the lower three bass courses are octave courses. Today the bajo sexto is used to accompany the accordion in conjunto music, laying down the boom-chang rhythm for the dancers and inserting occasional fills. In the late 1800s and early 1900s the bajo sexto played a more prominent harmonic role in the music. Luis Acosta described its role as “piano ambulante,” which he translated as “the left hand of the piano.”6

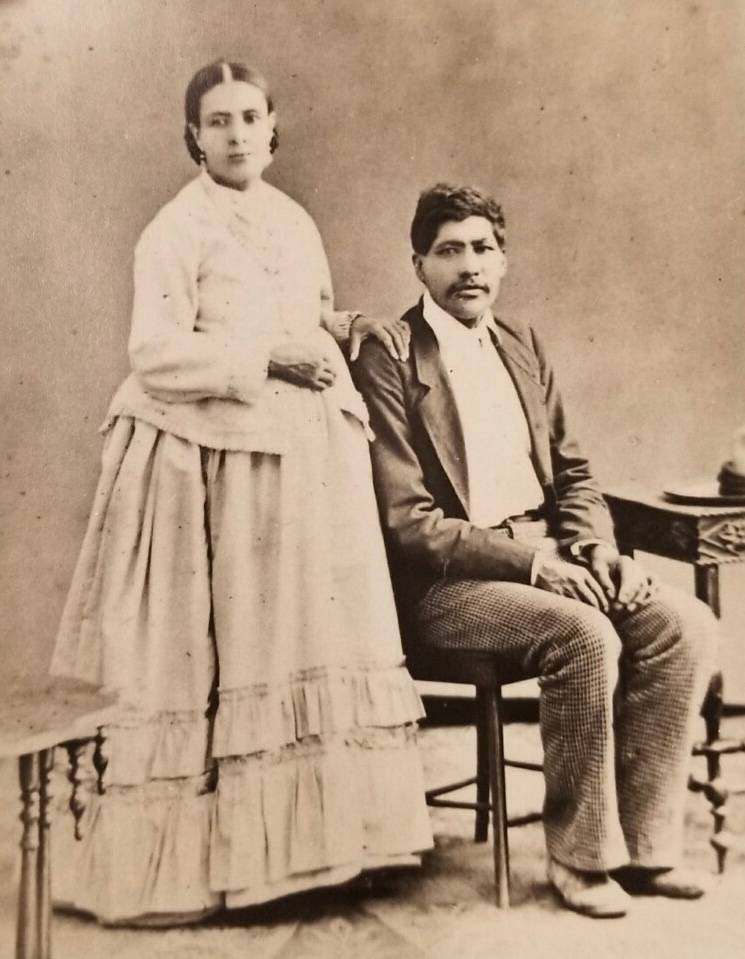

Guadalupe Acosta married Felisia Olvidares in 1903. They had their first child, Domingo, on May 6, 1904. Their second son, Luis Acosta, was born on May 4, 1906. At the age of 15 months, Luis contracted polio and was stricken by infantile paralysis. As a result, he lost the use of his left leg. When he was young, he got around on a small cart, similar to a skateboard, using his hands to propel himself. Later in life he would use crutches, and he eventually had his leg amputated due to diabetes and used a wheelchair.

In 1915, as the revolution intensified and violence escalated in Jalisco, Acosta and his family migrated north, first to Aguascalientes, where his daughter Refugia, nicknamed “Cuca,” was born. Luis Acosta would later tell one of his nephews that the family was in very dire straits during this time. They had no money; they were starving and there was much uncertainty in their lives. He described them as refugees from the revolution. From Aguascalientes they moved north to Nuevo Laredo, where Guadalupe found work as a carpenter and musician, building a few instruments on the side.

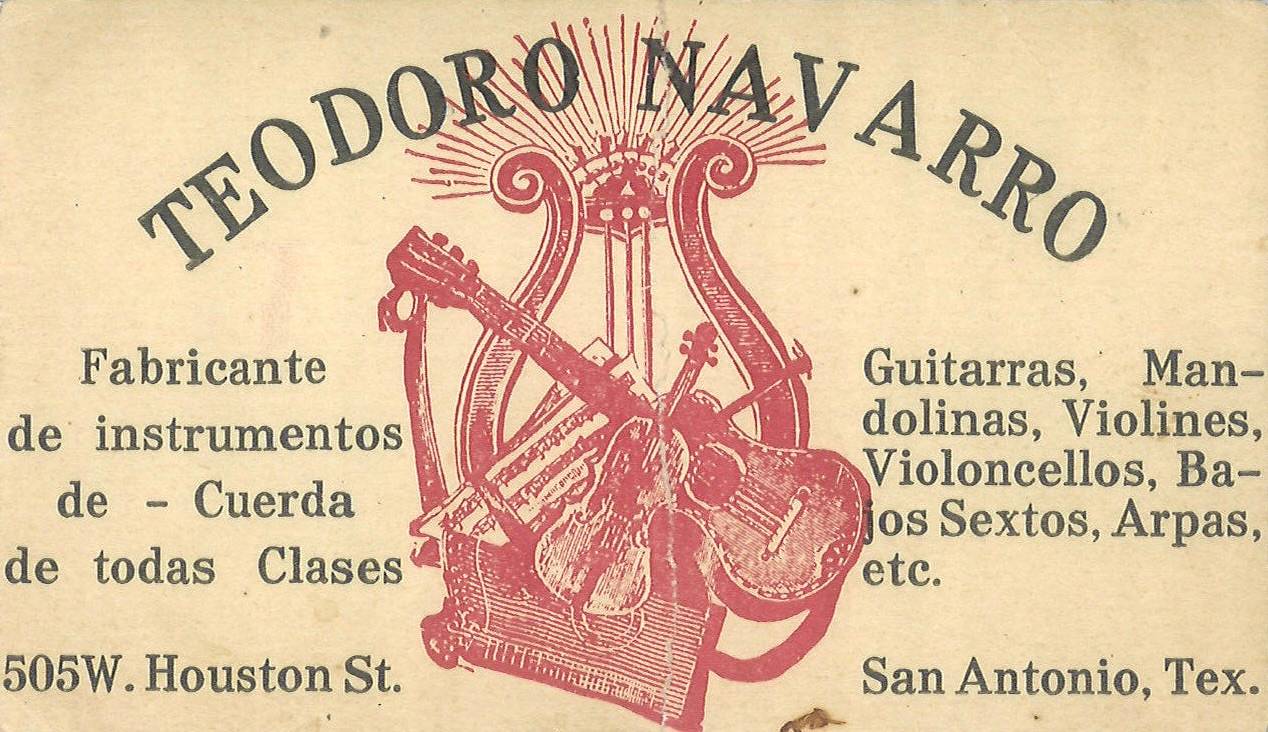

At some point during this time, Guadalupe met Teodoro Navarro, a luthier from Zacatecas who had also left his home due to the revolution. Navarro settled in San Antonio and opened a small shop at 505 W. Houston Street. Navarro encouraged Acosta to come to San Antonio and work for him. He said that he could sponsor him but would not be able to sponsor his family. Guadalupe would have to leave his family in Nuevo Laredo while he worked in the Navarro shop. Guadalupe arrived in San Antonio in 1917 and went to work for Teodoro Navarro, who paid him $12 to $15 per week. The shop made guitars, mandolins, violins, cellos, bajo sextos, and harps.

In addition to working in the Navarro shop, Guadalupe continued to work as a musician and as a carpenter. He saved his money and returned to Nuevo Laredo to see his family whenever he was able. His son Miguel was born in Nuevo Laredo on May 18, 1918. The family immigrated to San Antonio in 1920. Guadalupe’s wife, Felisia, put the children in a wagon and pulled them across the border. She covered young Luis’s legs with a blanket so that the immigration officials would not notice the condition of his leg. If they had, he would not have been allowed into the United States as people with disabilities were not permitted to immigrate into the country.7

The family initially took shelter in a hay barn near the Spanish Governor’s Palace and San Pedro Creek. Soon Guadalupe was able to purchase an abandoned shoeshine parlor at 514 W. Houston Street, near the present-day Alameda Theater. This shop was across the street from the shop of Teodoro Navarro, which was at 505 W. Houston. Luis described the building as narrow but very long. It had no insulation but was equipped with a small stove. The front part of the building was converted into a shop and the family lived in the back.

Guadalupe was joined in his lutherie work by his son Luis, who was then 14 years old. Luis was very intelligent and had gone to school in Nuevo Laredo. According to his family, Luis spent much of his time reading whatever books and magazines he could get his hands on. He could speak with people at length on a variety of subjects and was a very well-read, self-educated young man. It was not long before Luis took over the business operations of the shop, negotiating with customers and corresponding with people around the world.

Guadalupe’s eldest son Domingo worked as a musician in and around San Antonio. Domingo originally played the violin, but at a certain point he was in an accident and injured his hand. At that point he switched to the double bass. Domingo played bass in a variety of settings, from the San Antonio Symphony to orquesta típicas and jazz bands. He was regarded as one of the best jazz bassists in the state and was nicknamed “Chief” Acosta. He also played with Emilio Caceres, who billed himself as “the hottest violinist in the world.” Early in his career Domingo gave a good portion of his earnings to his parents to help the family get settled in San Antonio.

In 1926, as the family and business became established in San Antonio, Guadalupe was able to purchase a home at 2214 W. Travis Street. He and Felisia had three more children while living in San Antonio, Francisco (Frank), Jesus (Jesse), and Santiago. He also moved the shop to a new location at 526 W. Houston Street. At some point in the late 1930s, he moved the shop to its final location at 608 W. Houston Street. Initially instruments were made at the shops on Houston Street, but as the business expanded to include the sale of sheet music, records, and accessories, production was moved to a shop that Guadalupe had built behind his Travis Street home.

Guadalupe and Luis Acosta were joined in their work by Martin Macias. Macias was born on June 29th, 1898, in Zinapecuaro, Michoacán. Macias said that he learned the trade of lutherie from a Spaniard in Morelia, Michoacán. It is unclear when Macias began working with the Acostas. He is listed in a 1929 San Antonio City Directory as a “clerk at Acosta Music.” In a 1985 interview with Francisco Gonzalez, Miguel Acosta said that Martin Macias worked in the Acosta shop for 14 years. He described his father, Guadalupe, as Macias’s padrino, which translates to godfather, but in this case it is more likely akin to a sponsor or mentor. Guadalupe Acosta helped Martin Macias get established in San Antonio by giving him reliable work, in the same way that Teodoro Navarro had helped Acosta get his start. Miguel Acosta said that he only learned to build instruments from two people, his father, Guadalupe; and Martin Macias. The musician Jesus “Chucho” Perales remembered meeting Martin Macias in the early 1940s, “while he was working in the Acosta shop.”8 In addition to working in the Acosta shop, Macias began making instruments under his own name at some point in the 1920s or 1930s.

A catalog from approximately 1929 gives tremendous insight into the activities of the Acosta shop, and the musical tastes of San Antonio during that time. The catalog lists the various instruments that they made at the shop, with ranges in prices based on the woods and ornamentation. Bajo sextos ranged from $20 for a plain one made of poplar, to $50 for instruments made of walnut, mahogany, or Spanish cedar, in an extra-large size in the style of León, Guanajuato, with black and white rope binding around the top and back. Strings for the bajo sexto were available in bronze or copper for $2.75 and steel for $2.50.

Twelve-string guitars were listed as guitarra dobles. These types of 12-strings were tuned like a standard guitar, though sometimes tuned down a step or two. They had six pairs of strings, and each pair was tuned in unison. On a modern 12-string, the first two pairs are tuned in unison and the bottom four are tuned in octaves. The guitarra dobles ranged in price from $17 for an instrument made of poplar to $35 for one made of mahogany, Spanish cedar, or walnut, with black and white purfling around the top edge. A set of strings cost $2.

Guitarra séptimas were available with either eight or eleven strings and ranged in price from $14 to $35. The guitarra séptima is a seven-string guitar on which some string courses are doubled and some are single. The manner of stringing is largely up to the player. Originally, they were 14 strings but as time went on players began stringing the treble courses as single strings, which resulted in a ringing clarity. This practice recalls baroque players who would leave single strings on the first and sometimes second courses. These single strings are called chantarelles. The guitarra séptima was very popular at the end of the eighteenth and throughout the nineteenth century, but its popularity began to wane in the 1920s.

Six-string guitars ranged from $10 to $20. No custom strings were available for the six-string guitars. The catalog advertised Gold Seal strings for $.75 per set or Black Diamond strings for $1.05. The mandolins ranged from $10 to $15. Eighteen-string bandolones ranged in price from $18 to $35. They also made Hawaiian guitars for $35, and ¾-size double basses which ranged in price from $70 to $150, and Zacatecana harps for $35. Accessories were available for all the instruments the Acostas made as well as for violin, cello, saxophone, clarinet, and tenor banjo. They sold a wide variety of sheet music for waltzes, one steps, fox trots, paso dobles, and polkas.

A photo of Guadalupe Acosta in his shop around 1940 gives an idea of the variety of instruments he and his workers produced. In the case in front of Acosta there are several mandolins and violins. Though he may not have made the violins, Luis Acosta specialized in repairing them for local musicians, including members of the San Antonio Symphony Orchestra, and he also rehaired violin bows. A bandolón and an upright bass (likely made elsewhere) are in the foreground. Behind him, in the glass cases, there are several six- and 12-string guitars. The 12-strings appear to all be guitarra dobles, which were very popular in San Antonio at the time, though that would change in the coming decades. A photo of Lydia Mendoza hangs on the case behind Acosta. There are also several commercially made instruments in the cases, such as ukuleles, banjo ukuleles, and a bowlback mandolin.

The production of strings for instruments is a unique aspect of the Acosta shop. Because many of the instruments they manufactured were very specialized, strings from large-scale commercial string companies were not available. As a result, they made their own sets. Guadalupe Acosta was the person in the shop who specialized in making strings, though Martin Macias made his own when he opened his own shop. This is likely a skill that Guadalupe learned from his family while living in Lagos de Moreno. The making of a musical instrument string involves winding an outer wrap around a solid core. The core could either be made of animal intestine (usually cat, sheep, or pig, with each variety giving a different tone) or wire (usually steel). The wrap could be a thinner piece of gut, or very fine silver, copper, nickel, bronze, or steel wire. The material used and the thickness of the core and wrap is dependent on the intended instrument, the placement of that particular string, the desired tension of the string, and the desired tone. Determining the gauges of wire is a science and an artform, one that is completely separate from the art of lutherie. The machine that winds the string spins both ends of the core wire, while the string maker wraps the core with the thinner material evenly with constant pressure. The string cannot be too tightly or loosely wrapped, or it will not have the proper tension and it will not produce the proper sound.

Guadalupe Acosta made steel strings for bajo sexto and guitarra doble and gut strings for violin, harp, and guitarron. Acosta’s early string machine was run off a foot-powered treadle, similar to an old sewing machine or spinning wheel. The core was pulled tightly and attached to hooks on both ends of the machine. The thin wrap was tied into the loop end of the core, which would later be attached to the bridge or tailpiece of the instrument. Guadalupe used his feet to push a pedal up and down, which in turn spun pulleys on either end to which the core of the string was attached. As the core spun, he would feed the wrap evenly along its length. A great amount of care was taken for each string. Strings were assembled as sets and packaged. In later years the machine would be outfitted with an electric motor.

Many of Guadalupe Acosta’s grandchildren remember him sitting on the porch of his Travis Street home, making strings in the evening while he listened to mass or the rosary being read on the radio. They remember the whirr of the electric motor and his methodical movements as he wound one string after the other. His granddaughter Grace Sandoval (daughter of Refugia or “Cuca”) remembers being sent to purchase wire for the strings at the local molina, where tortillas were made, and at the San Antonio Candy Company. It is possible that the tortilleria had the fine wire to remove the raw, flattened tortilla from the press. The candy company likely used the wire in its manufacturing process as well. Grace also remembers her grandfather packing up the strings and mailing them all over the country.

Luis took on a variety of duties at the shop. He corresponded with customers at the shop and outside San Antonio, and he operated a small printing press at the shop to produce catalogs, songbooks, and promotional materials. He was also the contact person for northern record companies who traveled to San Antonio to record local Tejano musicians, and he recommended musicians for these recording sessions.

The first of these sessions was organized by the OKeh Records, which was a subsidiary of industry giant Columbia. OKeh had pioneered these remote recording sessions, under the direction of Ralph Peer, in cities like Chicago, St. Louis, Atlanta, New Orleans, and San Antonio, to find musicians who were outside of the talent pool located in New York. Ralph Peer was one of the first people to realize there was a market for music outside of the popular and classical music that was the focus of the larger labels like Victor and Columbia. As a result, OKeh was one of the first labels to record American vernacular music like jazz, blues, and hillbilly. They were the first to go to Texas in search of talent. Eventually other labels, including Columbia and Victor, began to follow suit. Columbia purchased the OKeh label and Victor hired Ralph Peer as an executive and producer.

It was a common practice for record companies to contact local businesses that sold records and phonographs and ask about talent in their area. One example was Polk Brockman, whose family owned a furniture store in Atlanta which sold OKeh records. Brockman convinced Ralph Peer to record Fiddlin’ John Carson, the first hillbilly artist to record for OKeh. After successful sales of the Fiddlin’ John record, Peer began pursuing talent in related genres, eventually leading to the legendary Bristol Sessions, an early landmark country music recording session. Another example is H.C. Speir, who owned a music and record store in Jackson, Mississippi. Speir worked as a talent scout for a variety of labels including OKeh. He was responsible for launching the recording careers of blues artists like Charlie Patton, Son House, Skip James, the Mississippi Sheiks, and Robert Johnson. In San Antonio, Guadalupe and Luis Acosta played that role for Mexican American artists.

The first recording session in San Antonio took place from March 3 to 14, 1928. It was an eclectic session capturing a variety of blues, jazz, and old-time musicians. Some of the artists who were recorded were fiddlers Oscar Harper and Prince Albert Hunt and blues singer Texas Alexander. It was also one of the first sessions to devote significant time to recording Mexican American musicians and groups. The first three days were dedicated solely to these groups. The most significant Mexican American group to be recorded at that session was the Cuarteto Carta Blanca, which was composed of members of the Mendoza family, father Francisco, mother Leonor, and daughters Maria and Lydia. The 12-year-old Lydia played mandolin on these recordings. The family was paid $7 per side, with no offer of royalties, a total of $140 for the 20 sides they recorded.

Another important artist who recorded at that session was the blues and jazz guitar pioneer Lonnie Johnson. Johnson was one of OKeh’s star performers, and he had accompanied the recording team from New York. They had previously completed a session in Memphis on their way to San Antonio. In San Antonio Johnson made some solo recordings and worked as an accompanist to the singer Texas Alexander. The two recorded three songs together right before the Quarteta Carta Blanca recorded their second session. It is likely that they passed each other in the hall or had some interactions during the time between sessions. Lonnie Johnson remained in San Antonio through the spring and summer of 1928, playing frequently at the Japanese Tea Garden. While in San Antonio, Lonnie Johnson purchased a 12-string guitar from the Acostas. In 1960 Johnson told the British blues researcher Paul Oliver, “I bought that 12-string guitar in San Antonio. . . . They only make 12-string guitars in San Antonio. The Mexicans and Spanish that’s all they use.”9 He would return to New York with the guitar and go on to use it on a variety of blues and jazz records with artists like Victoria Spivey, Eddie Lang, Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, and the Chocolate Dandies.

Okeh returned to San Antonio in 1929 and 1930. Guadalupe Acosta’s orquesta recorded during the 1930 session, as did Juan Gaytan and Francisco Cantú, both of whom are pictured with guitarra dobles made by the Acostas. The guitars can be identified as Acostas because of the style of bridge, which was a design unique to the Acostas.

Luis also worked with the Vocalion, Decca, and Bluebird labels during their recording field trips to San Antonio. Pedro Rocha and Lupe Martinez, who recorded for Vocalion in 1929, were photographed with an Acosta guitarra doble and guitar. During the 1920s and 1930s the guitarra doble was the most popular type of guitar in San Antonio, as older instruments like the guitarra séptima and bajo sexto fell out of favor. Both were considered old fashioned, and the bajo sexto was considered too rustic or crude, reminding people of the life they had left behind in Mexico rather than their new lives in the United States.

A popular place for musicians to perform was the Plaza Zacate, or Haymarket Square. During the day, the plaza was an enormous farmers market full of people who drove in from the country to sell their wares. At night, after the farmers had gone home, the plaza would transform into a flea market and a series of baratillos, inexpensive food stands selling tamales, tacos, or chili con carne. The plaza was a gathering place for people to socialize and be out and about. According to Lydia Mendoza, there were a number of bands that would perform at the plaza. Most of them were guitar trios who would stroll along, playing from group to group or for cars that would drive through to get a bite to eat. She said that in the early 1930s the accordion had not yet made its presence known in the Plaza Zacate. The Mendoza family would play in the plaza at a friend’s food stall. They did not stroll or run after cars that had pulled in.10

It was around 1932 when Lydia started playing the 12-string guitar. Lydia’s first 12-string was actually an Acosta bajo sexto which had been converted by Guadalupe Acosta to be used as a 12-string.11 She also made some changes to the way the guitar was strung.

Well, when we arrived in San Antonio, all those musical groups had their twelve-string guitars, guitars like the one I’ve got. But their strings were tuned differently: it’s logical that a twelve-string means that it has to have two firsts, two seconds, two thirds, two fourths, two fifths, and two sixths. All pairs tuned the same, like the mandolin which is tuned that way . . . . It has a very interesting tuning. So I thought: “I’m going to tune my guitar another way.”

That’s when I got the idea of tuning one string high and one low, and the next . . . and so forth. That’s why the sound of my twelve-string is very different. It occurred to me to string it up in a different way. I imagined it would sound more beautiful. For example, the third string is at a certain pitch. If you combine it with a first string, the first string will be higher in pitch than a first string in its normal place. You raise its tuning so it will be at the same pitch as the third. It will sound the same, only an octave higher. The end effect is a different sound. And that’s how I have tuned my guitar. That’s how I have developed my own ideas; to the limits of my own intelligence, see?12

While Lydia’s tuning may have been unique in San Antonio, it was the standard 12-string guitar tuning for players outside the city. Players like Huddie “Lead Belly” Ledbetter and Willie McTell tuned their 12-string guitars with the top two or three treble strings tuned as unison courses and the remaining bass courses tuned in octaves. The arrangement is similar to that of a bajo sexto, which has both octave and unison courses.

In March of 1934 Lydia Mendoza went into the recording studio, this time with the Bluebird label, to record with her family band, now named Quarteto Monterrey. She switched from mandolin to violin, while her sister Maria played mandolin, one that was made in the Acosta shop. Lydia made her solo recording debut on March 27, 1934, with her masterpiece “Mal Hombre,” a song which she first learned from chewing gum wrappers that she would buy as a girl while living in Monterrey. She would go on to have a very successful career, recording hundreds of records with a variety of labels and becoming one of the few Mexican American artists to be recognized by mainstream American audiences. In 1977 she performed at the inauguration of President Jimmy Carter. In 1982 she was awarded a National Heritage Fellowship by the National Endowment of the Arts, the first Texan to receive this honor. In 1999 she was awarded the National Medal of Arts by President Bill Clinton, and in 2013 she was commemorated with a United States Postal Service stamp. She played at least three different Acosta 12-strings early in her career.

Around 1932, at the age of 14, Miguel Acosta started working in the shop. By this time Miguel was an accomplished musician. He had learned to play the bajo sexto from his father at the age of 11. By his teens he was playing with his father at parties and dances in San Antonio. During the Depression, in addition to working in the shop, Miguel played bajo sexto in a Works Progress Administration (WPA) orquesta with his father. In the 1920s and 1930s he played in guitar trios, accompanied fiddlers, played in small ensembles, and serenaded people in their homes. He also played in many tent shows of the time including Carpa Garcia, Carpa Cubana, and Carpa Jackson in Robstown, Texas. When he was 15, Miguel played with Rosita Fernandez on a radio show on WOAI. He was hired to work as a strolling troubadour at the Gunter Hotel in 1937 concurrently with Robert Johnson’s historic recordings for Vocalion at the hotel. During the late 1930s and 1940s he recorded as an accompanist with many musicians including Eva Garza, Gaytan y Cantu, and Benjamin Martinez. Miguel was not credited on any of these recordings.

The group of Guadalupe, Luis, and Miguel Acosta, along with Martin Macias, was responsible for reaching a peak of production for the shop, and it was a very important time for the development and evolution of the bajo sexto.

While the guitarra doble dominated the 1920s and early 1930s, a change was soon to come. On October 21st, 1936, in San Antonio, the Bluebird remote team recorded an accordion player named Narciso Martinez. Martinez was known as el huracán del valle (The Hurricane of the Rio Grande Valley) due to his fast playing on the two-row button accordion. Just as impressive was Martinez’s accompanist, Santiago Almeida, who showed an equal amount of dexterity on the bajo sexto. The records made by Martinez and Almeida are credited as some of the earliest in the genre known as conjunto, which was born from a cross-pollination of German, Polish, and Czech immigrants, and Mexican Americans. Not only did the European immigrants introduce Mexicans and Mexican Americans to the accordion, but they also introduced them to their dance tunes, like polkas and schottisches.13 In conjunto the accordion is ever present. In the early days of conjunto, accompaniment was provided by either guitar or bajo sexto. After Martinez and Almeida made their debut, the relationship between the accordion and bajo sexto was cemented. In the earliest photos of the duo, Santiago Almeida is playing an Acosta bajo sexto.

Soon demand for the bajo sexto outstripped that of any other instrument that the Acostas produced. Mickey Acosta (son of Miguel) told me, “In the old days they would make a dozen six-string guitars followed by a dozen 12-strings (guitarra dobles). Eventually nearly everything they were making was bajo sextos.”

The bajo sexto is a folk instrument which is thought to have originated in Central Mexico. It was originally made by rural luthiers in Michoacán, Zacatecas, Jalisco, Guanajuato, and San Luis Potosí. The instrument was used in bands as accompaniment to the violin, trumpet, flute, or other solo instruments, in addition to accompanying corridistas or ballad singers. Initially the instrument was looked down upon by high society as it had originated with the lower classes. Eventually, though, it was embraced by elites as a nationalist symbol, something of pure Mexican origin. The bajo sexto was used in an upper class orquesta típica under the direction of Italian musician Carlo Curti. In 1884 Curti’s orquesta was chosen by President Porfirio Díaz to represent Mexico at the 1884 World’s Fair in New Orleans. Due to its newfound association with the upper classes, the bajo sexto began to lose some popularity during the time of the revolution.14 As the revolution intensified and people began to flee their homes in central Mexico, luthiers like Guadalupe Acosta, Martin Macias, and Teodoro Navarro brought their ideas of the instrument with them. They initially built very traditional models, which mirrored the instruments that were made in Mexico, but they began to slowly make changes in their designs.

It is difficult to ascertain the specifications of the bajo sexto designs these luthiers brought with them from central Mexico to San Antonio, as antique instruments from both Mexico and San Antonio are quite rare. The 1929 Acosta catalog mentions “an extra large size in the style of Leon, Gunanajuato, Mexico.” One thing that I have noticed, after examining some of the early instruments that did survive and the photographic record of musicians, is that the bodies of the early instruments tended to get larger as time went on. Two bajo sextos made by Herculano Carillo in San Luis Potosí around the turn of the twentieth century had body lengths of 19¾ inches and a lower bout width of 14 inches. The earliest known Acosta bajo sextos (like those in the photos of Santiago Almeida) had a body length of 20½ inches and a lower bout width of 15½ inches. These were the same measurements that Martin Macias used for the vast majority of his bajo sextos. By the late 1940s and early 1950s, the Acostas were making bajos that had a body which was 21½ inches long and 16 inches wide at the lower bout. Larger body sizes were a general trend in the guitar world at large during this time.

Though body size increased, there were some critical elements of the bajo sexto that remained the same. Most importantly, the scale of all the instruments I surveyed was the same, 25½ inches. Another example was the shape of the neck, with a nut width varying very slightly, between 21/16 inches and 2⅛ inches, and a neck depth that was slightly over one inch at the first fret. Though the body shape and size might vary, the feel of the neck and tension of the string would remain the same. Another integral feature which remained largely unchanged was the bracing of the spruce top of the instrument. All the instruments surveyed had four lateral braces running perpendicular to the grain of the top, with three braces under the bridge running parallel to the grain of the top. These braces helped to counteract the tension that the strings created on the top by the bridge. Each maker varied in their placement of other braces that ran parallel to the grain. Carillo used three additional braces in front of the bridge and none behind. Acosta used one in front of the bridge and one behind, running along the center seam of the top. Macias used three in front and three behind.

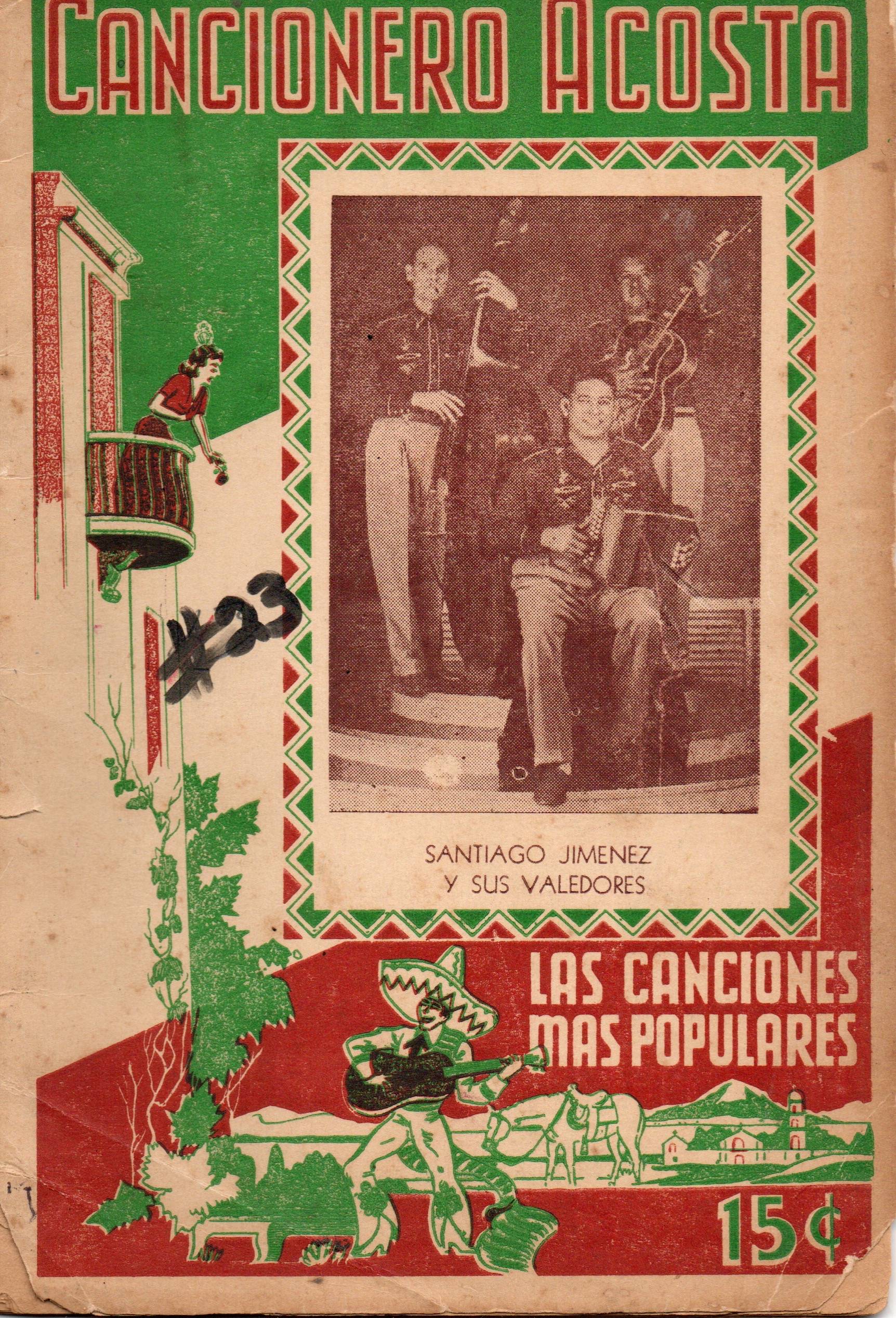

In the 1930s Luis Acosta started to print cancioneros, or songbooks, which contained both traditional and popular songs of the day. The songbooks featured the photo of a popular musician on the cover. He sold these in the store individually for $.15 and offered yearly subscriptions for $1.50. Only a few examples of these cancioneros have survived, and they are very insightful as to the range of services that the Acosta shop provided and which songs were popular during the time. These cancioneros played an important role in the circulation of songs. Santiago Jimenez, Jr. told me that his family had a few of the Acosta cancioneros and that he remembered studying them as a boy, trying to learn each song.

Both Luis and Miguel Acosta brought a youthful and creative energy to the shop. Luis, who was somewhat confined to the shop due to his handicap, relished challenging woodworking projects. In 1940 he created a striped guitar made of alternating pieces of walnut and cottonwood. The guitar was a play on patterns, very artistically designed and wonderfully executed. He was featured with the guitar in the local newspaper, the San Antonio Light. A caption under the photo read, ''Luis Acosta makes his guitar the hard way. This Instrument contains 4100 small pieces of wood. Acosta, a San Antonio instrument manufacturer, spent six hard weeks fitting the tiny pieces into a well-toned instrument. He didn't make it to sell; he just made it for the heck of it. Woods include black walnut, cottonwood, spruce and mahogany.''15 The guitar is a testament of his skill, patience, and artistry.

Another unique and incredible instrument that came from the Acosta shop, which either Luis or Miguel made, was a 14-fret super-jumbo checkered guitar. Mickey Acosta told me that his uncle Luis had made the guitar. Yet there are several photos of Miguel playing the guitar in the early 1940s. The body and neck of the guitar are made up of one-quarter inch alternating squares of spruce and Brazilian rosewood laid out in a checkerboard pattern. These checkers are glued to a mahogany substrate to give the wood some structural integrity, the same technique used on the striped guitar. The attractive pattern, which extends to the neck and sides, is playful for the eyes of the viewer. There is a triangular band across the back, which breaks up the checkered pattern. The back of the guitar recalls the shell of an armadillo, which was sometimes used as a back for South American stringed instruments like the charango.

In addition to being a visual feast that incorporates a Mesoamerican motif, the checkered guitar also incorporates features which were becoming popular in the guitar world at large. One noteworthy feature is that the neck of the instrument has 14 frets to the body, as opposed to 12 which was the tradition. The additional frets on the neck allow one to play higher notes with greater ease. This feature became popular in the late 1920s and early 1930s. Another unique feature is the width of the body, which is a whopping 17 inches, a feature that Gibson Guitars used on their Super Jumbo guitars beginning in 1938. This guitar shows that the Acosta brothers were paying attention to guitars beyond the traditional instruments that their father and his contemporaries were making. They were incorporating their traditions, but they were not bound by them. It is a uniquely American piece.

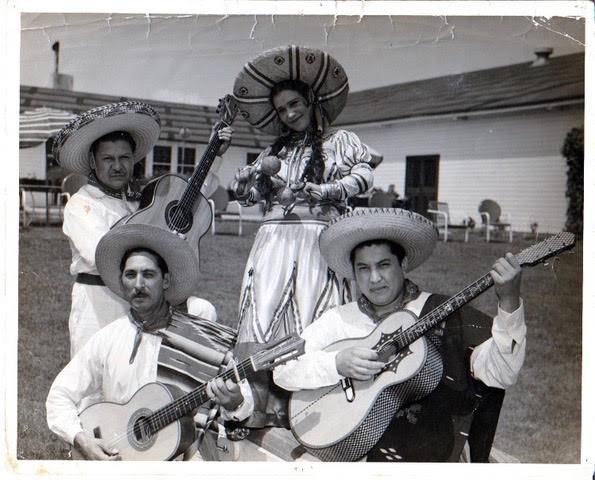

Because Miguel was a working musician, he often made instruments he could play in performance. He created instruments that were very utilitarian but also aurally and visually pleasing for the listener. A perfect example is the double neck six-string/bajo sexto, which he made for himself in the early 1940s. The guitar also created a spectacle which helped to attract listeners, especially when he was playing for tips. In the only surviving photo of the guitar, Miguel is playing for tourists along with three friends at the San Antonio train station.

As the US entered World War II, affairs changed dramatically at the Acosta shop. Wood for instruments was hard to come by, and wire used for string production was also unavailable. Young men had to serve in the armed forces or work in essential services. Martin Macias left to work in agriculture and for a time Miguel went to work painting delivery trucks. In 1945 Miguel, who now had four children, enlisted in the US Army and trained as a paratrooper. Miguel arrived in Germany two weeks before the Germans surrendered, after which he was part of the occupation forces stationed in Berlin. Before long Miguel’s musical talents were recognized and he was assigned to work as an entertainer for the troops and officers. During this time he made a series of records on a type of home recording machine which recorded onto acetate discs. The records still exist and his repertoire is very enlightening. In addition to swinging versions of Latin songs like “Cuatro Vidas” and “Nosotros,” Miguel also recorded “Carioca,” a popular song from the 1933 Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers film Going Down to Rio. Miguel and his partner also recorded the Texas standard “Steel Guitar Rag” as well as a hot boogie-woogie. Much like the instruments he was making, Miguel’s music was not bound by tradition or expectations.

After he returned from the war, Miguel trained as an electrical technician under the GI Bill. Initially he went to work at Kelly Air Force Base in San Antonio, but the pull of his parents and the shop was too strong, and Miguel went back to building instruments, though with some new skills under his belt. One of the first instruments he created upon his return was another double neck six-string/bajo sexto, but this one was electrified. It was equipped with two D’Armond pickups in the two sound holes and was wired with a toggle switch to select pickups, and a volume knob for each pickup. The entire instrument was a testament to Miguel’s skill at inlay and design, with inlays around the volume knobs and the entire perimeter of the instrument. Between the bridge and sound hole, he inlaid “Acosta. 1947”, to give no doubt as to who made it or when it was made. This instrument was made 11 years before the Gibson Guitar Corporation would make their first electric double neck six/12-string guitar. It was a bold, futuristic instrument rooted solidly in tradition. His son Mickey told me that he thought the guitar was a way for his father to deal with his PTSD from being stationed in Berlin at the close of the war. Though the major fighting was over, Miguel witnessed a lot of destruction and brutality in Germany. He certainly poured his heart and soul into that instrument, which is a masterpiece.

During this time Miguel also designed a guitar with a built-in internal amplifier. Though the guitar does not survive, a schematic does. It is yet another example of Miguel’s innovative work.

After the war the Acosta shop saw major changes. Martin Macias had gone on to start his own shop in a two-story stucco building at 1130 Division Avenue. He no longer worked for Guadalupe and would now be his competition. Luis focused on managerial duties at the Houston Street store, selling instruments and accessories like strings, records, sheet music, and songbooks, and repairing violins. The only instruments he made during this time were castanets, which he carved by hand. Luis stayed at the shop and had a bed and bathroom in the back of the building. He would go to his parents on the weekends for dinner and to socialize with family and friends. Production of instruments was moved to the Travis Street location and was performed by Guadalupe and Miguel.

Miguel continued to play music in and around San Antonio during this period, and in the early 1950s his daughter Sylvia started performing with him. Sylvia sang and played guitar. She said that everyone around town liked her father for his outgoing personality. He was quite well known for his musical abilities. She said that most of their gigs were for “society people” at venues like La Villita, the Fort Sam Houston Officers Club, the San Antonio Country Club, the Gunter Hotel, and various conventions. They performed in elaborate outfits which were made by Miguel’s wife Octavia, who was a very talented seamstress in her own right. Sylvia performed with her father until she was married in 1958.

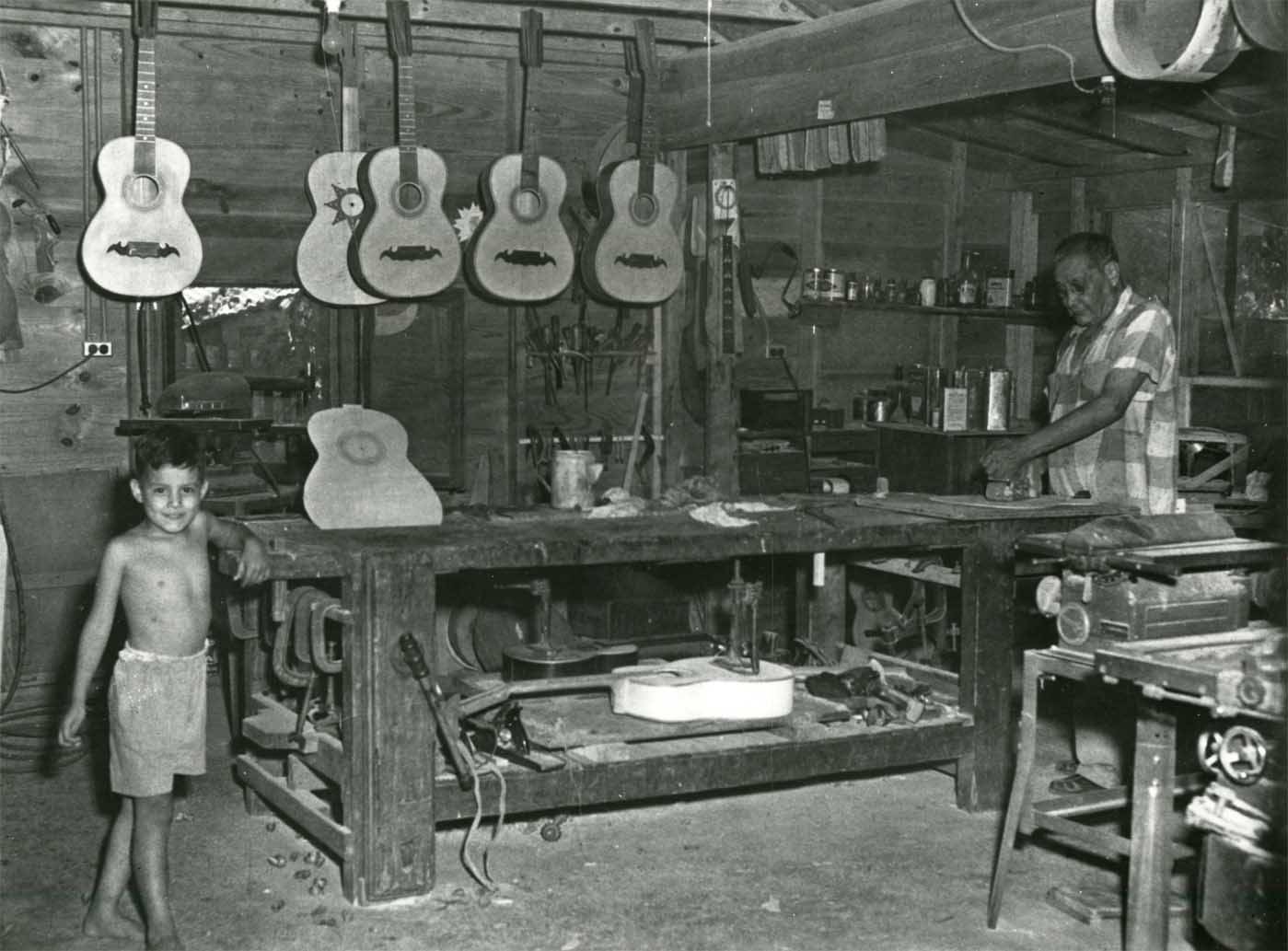

A 1954 photo of Guadalupe Acosta working in his Travis Street workshop demonstrates Mickey Acosta’s point that as conjunto became more popular, demand for the bajo sexto outstripped the variety of instruments that the family had made. Five unfinished bajo sextos hang from the ceiling of the shop. A dusty bandolón hangs in the background. Another bajo is under the bench while the glued bridge dries. There is a small six-string being glued under the bench as well. Their method for gluing bridges was to use a jack from a Model T Ford as the clamp, and the weight of the bench to counter the jack. It is a very unorthodox method by today’s standards, but it proved effective. Of all the Acosta instruments I have studied and evaluated, none of them had a loose bridge. At 70 years old, Guadalupe is at his bench using an electric sander to sand a spruce top. Many other power tools are visible, including a table saw, a joiner, and a drill press. Guadalupe’s grandson Rudy stands shoeless and shirtless, smiling at the photographer.

Determining the number of instruments that the Acostas produced is somewhat difficult, but it is certainly a great number. From interviews and photographs we know that the instruments were mostly built in batches of five or six in an assembly line fashion. In a 1984 interview with Jim McNutt, Miguel said that each member of the crew would be assigned a different part of the guitar to work on. One person would bend sides for six guitars, another would work on six necks, another on six tops and backs, while a fourth assembled parts.

The photos of the Acostas working in the shop show this type of assembly line work. In a 1937 group of photos from the San Antonio Light,16 Guadalupe Acosta bends guitar and bandolón sides on an electric iron that he has clamped in a vice. It is a household electric clothes iron, but the corners had been filed off and rounded so that it could bend curved shapes. There are sides for three guitars and two bandolóns. Around the corner of the same bench, Guadalupe’s son Luis is working on rough neck blanks. He has a bandolón neck in the bench vice and is using a frame saw to cut away material to round the heel. Four completed necks sit before him on the bench. In another photo, further down the same bench, his brother Miguel uses a chisel to carve the heel of a neck of a guitarra doble body. Four more necks sit on the table in front of him. The back has not yet been attached to the instrument, and one can see how the guitar is fan braced. In a fourth photo their younger brother Jesse works at the same bench, gluing the top onto the neck and sides of a six-string guitar.

Guadalupe Acosta said that it took about 12 days to make a guitar.17 During much of that time the guitar sat idle while glue or varnish was drying. For this reason, several instruments were built at the same time. We can assume that at their peak production in the 1930s, they were making a batch of six guitars every two weeks, which is approximately 150 guitars per year. In the early days when the crew consisted of Guadalupe, Luis, and Martin Macias, the production decreased slightly to approximately 75 to 100 instruments per year. In later years, as the workforce consisted of an older Guadalupe and Miguel, approximately 60 to 100 instruments were built. By the late 1960s and early 1970s, at which point only Miguel was actively making instruments, he was likely making 25 to 50 guitars a year. The shop was open from 1920 until around 1972, when it was torn down due to urban renewal. In that 52-year span, it is safe to assume that the Acostas produced thousands of instruments.

After the Acostas closed their business in 1972, Miguel began playing more music, sometimes two or three gigs in a day. He continued to produce instruments at a shop he had built behind his home, but the number of instruments he made dramatically decreased. Many of them were fun projects which he made for himself. During this period he made a guitarron that he played with a mariachi group. He also made a guitar in the shape of a fish and an 18-string bandolón. He would take special orders but the pace at which he built was much more leisurely.

Luis Acosta passed away in 1975 due to complications from diabetes. Guadalupe Acosta passed away on August 12, 1979. He was 93 years old.

In 1984 Miguel Acosta was introduced to Jim McNutt, a graduate student at the University of Texas at San Antonio. McNutt began the process of documenting Miguel’s life and work. He conducted extensive audio interviews with Miguel, took dozens of photographs, and filmed Miguel building a bajo sexto. The material that Jim McNutt gathered is an invaluable resource. It is likely the most extensive documentation of a luthier of Miguel’s generation, and it illuminates the way guitars were made, especially in the Spanish tradition, and the tools that were used prior to widespread availability of power tools.

Rudy Gallegos, a San Antonio luthier and musician who knew Miguel Acosta, told me that Miguel would often visit the Macias shop, where Martin Macias’s son Albert took over after Martin passed away in 1983. Miguel and Albert would talk shop and play music, continuing the collegial relationship that existed between the two families since the early 1920s. Miguel Acosta passed away on November 3, 1998.

Though none of the Acosta family carried on the building of acoustic guitars and bajo sextos, many of Miguel's sons spent some time working in the trade. His sons Mickey, Sonny, Louis, and Jimmy all spent time working for C. Bruno, a large musical instrument importer based in San Antonio. Their work consisted of inspecting instruments which had been imported from Japan and making adjustments to make them more playable before they were shipped off to music stores around the country. They also worked in the repair department of Caldwell Music in San Antonio. In the early 1970s Miguel’s eldest son Mickey started his own music store, Acosta Music Company, where he repaired and sold band instruments and guitars. Because of his skill and experience, Mickey was a very well-known repair person in San Antonio. In addition to repairing instruments, Mickey built electric guitars and wound magnetic pickups. He also worked as a machinist at Kelly Air Force Base. Mickey closed his store in 2014 and passed away on January 5, 2021.

The importance of Guadalupe Acosta and his sons in the development of Tejano music in South Texas cannot be overstated. Much of their legacy was overshadowed by their former worker Martin Macias, who is often credited with having developed the modern bajo sexto. The time that Martin Macias spent in the Acosta shop working alongside Guadalupe, Luis, and Miguel has largely been ignored or unknown, but it is critical in understanding Macias’s success as a luthier, and the evolution of the bajo sexto as it arrived in the United States.

In May of 2023 I was visiting Santiago Jimenez, Jr., and I showed him the Acosta Cancionero that had a picture of his father on the cover. It brought back a flood of memories as he told me about learning all the songs inside the book when he was a child. I asked him if he remembered the Acosta shop or Acosta’s instruments. He said he remembered going into the shop and interacting with Luis. Then he said, “We were always a Macias family. We didn’t have any Acostas.” I also asked him what kind of bajo he was playing with his father in Chulas Fronteras, the 1976 Les Blank documentary film. Jimenez said, “Oh! That’s an Acosta. That was a nice bajo!”

Then I asked, “What kind of bajo is Flaco playing in the picture of him and your dad in the early 1980s?”

“Oh! That was an Acosta! That was a nice bajo!”

It was a very telling interaction.

Though the work of Guadalupe Acosta and his sons has faded somewhat from public memory, their descendants have done an amazing job of preserving their legacy. The family has saved a treasure trove of instruments, photographs, and ephemera that were left over from the days when the shop was going strong. The cache of material in the Acosta Family Archive, along with the documentation done by Jim McNutt and the photos and videos preserved by UTSA, gives us an incredible insight into this family that played such an important role in the development and distribution of Tejano music.

Notes

1. Miguel Acosta, interview by Jim McNutt, 1984, University of Texas at San Antonio Digital Collections.

2. Ralph F. Graves, “Paracho—The Guitar Capital of Mexico,” El Ojo del Lago (website), 2013.

3. Robert Stevenson, Music in Mexico: A Historical Survey (Crowell, 1952), 92.

4. Luis Díaz-Santana Garza, “El bajo sexto: Símbolo y unificador cultural en la frontera México-Estados Unidos,” Acta Musicologica 88, no. 1 (2016): 49-61, Project MUSE.

5. Luis Acosta, interview by Chris Strachwitz, May 19, 1974, Arhoolie Collection.

6. Luis Acosta, interview.

7. Grace Sandoval, daughter of Refugia Acosta, in discussion with the author, December 2022. All conversations and interviews conducted by the author occurred from 2014 to 2023 at various venues, homes, and events in San Antonio, Texas, and by telephone. Subjects include Grace Sandoval, Francisco Gonzalez, Mickey Acosta, Michael Acosta, Sylvia Acosta-Rodriguez, Louie Acosta, Albert Acosta, Omar Leos, and Santiago Jimenez, Jr.

8. Jesus “Chucho” Perales, interview, Street Talk Magazine, n.d.

9. Lonnie Johnson, interview by Paul Oliver, Philadelphia, 1960, Paul Oliver Archive of African American Music, Oxford University.

10. Yolanda Broyles-Gonzalez, Lydia Mendoza’s Life in Music: La Historia de Lydia Mendoza (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006), 9.

11. Lydia told this to Francisco Gonzalez, who in turn told it to me.

12. Yolanda Broyles-Gonzalez, 79.

13. Manuel Peña, Música Tejana: The Cultural Economy of Artistic Transformation (College Station: Texas A&M University Press), 90-91.

14. Garza, “El bajo sexto.”

15. San Antonio Light, March 20, 1940, vol. LX, n. 47, Section B.

16. San Antonio Light, April 6, 1937, vol. LVII, n. 77.

17. “Faces of San Antonio,” San Antonio Express News, May 12, 1963.