JTMH Volume 24 | Reviews

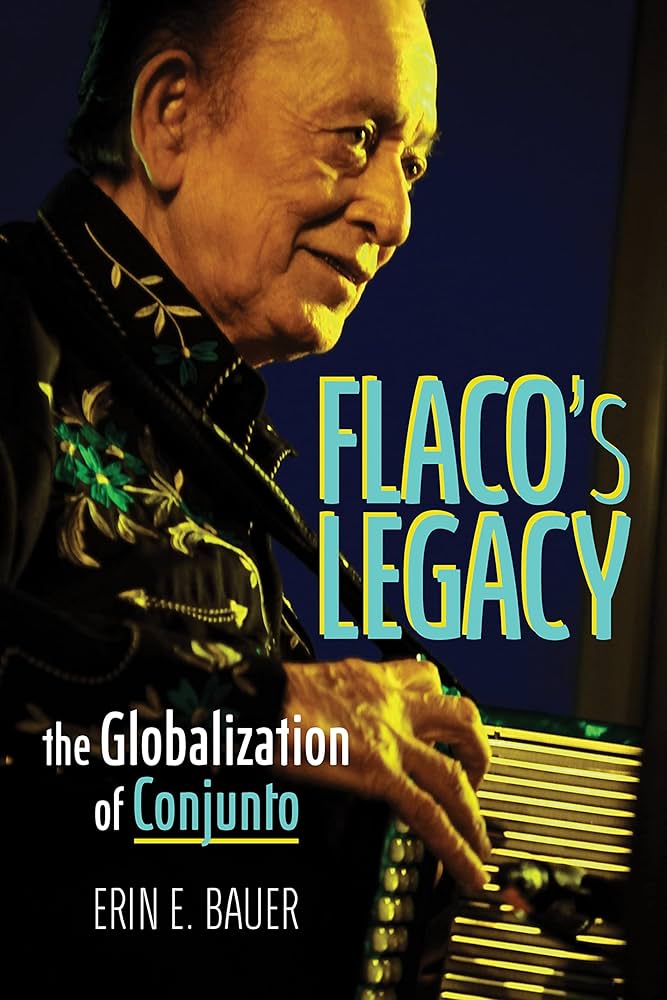

Flaco's Legacy: The Globalization of Conjunto

By Erin E. Bauer (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2023)

In spite of its significance within the context of Mexican American cultural expression as well as twentieth-century popular music, full-length monographs studying the Texas Mexican conjunto remain few and far between. With Flaco’s Legacy: The Globalization of Conjunto, Erin E. Bauer makes an important contribution to the still-growing body of academic writing about the genre through her sweeping, comprehensive snapshot of the conjunto scene, striking a balance between the technical aspects, given her expertise in musicology, and an insightful examination of the contemporary state of conjunto, presented in a more accessible manner.

Flaco’s Legacy takes us from conjunto’s sociohistorical origins in the borderlands to its presence on the global stage—and back again, as its spread inspired practitioners the world over to pick up an accordion and learn to play polkita rancheras like the best of them. Central to its analysis is the question of globalization, as encountered through media/migration, hybridization, and appropriation, vis-à-vis conjunto’s reach and influence internationally. Drawing from some familiar names in the field, including Arjun Appaduari and Nestor García Canclini, Bauer argues that globalization has led to the development of different styles of conjunto, “as distinctive local and global versions of Texas-Mexican accordion music exist simultaneously” (3), a process set in motion, in part, through Flaco Jiménez’s rise in commercial appeal, critical acceptance, and many collaborations with artists from a wide range of genres.

As perhaps the most widely known conjunto artist, it’s no surprise that Flaco figures prominently in Bauer’s study. He’s joined on these pages by Mingo Saldívar and the late, great Esteban Jordan, along with Eva Ybarra, Lydia Escobar, and other luminaries well familiar to conjunto fans. Readers who want a general history of more recent developments and popular performers in conjunto will appreciate the spotlight Bauer shines on these artists, too. Bauer writes about them lovingly, encapsulating biographic profiles along with a sorely needed scholarly analysis. Nowhere is this clearer than in her chapter devoted to women in conjunto, a far-too-brief and necessary intervention into the male-dominated world of Texas Mexican music. Bauer herself calls this “a preliminary entry in a long-neglected field of inquiry” (167), suggesting she will continue to pursue this worthy subject.

With the globalization framework as a backdrop, Bauer casts a wide net. Artists and bands like Kenji Katsube, Dwayne Verheyden, Los Lobos, and Dutch rock band Rowwen Hèze also appear, introduced and contextualized through their relationships with conjunto. Certainly, fans of the genre are likely to be familiar with Katsube and Verheyden, at the very least from their presence at the Tejano Conjunto Festivals. While East Los Angeles’s Los Lobos primarily plays rock ‘n’ roll, they have nonetheless incorporated Texas Mexican conjunto selections into their repertoire throughout their five decades of playing, and serve as an example of a band connected to yet pushing the limits of the genre.

At other times, however, this expansive genealogy of conjunto seems tenuous at best. Rowwen Hèze names Los Lobos as a major influence, covering several of the Chicano band’s accordion-and-bajo sexto-led songs, and their inclusion here is merited largely upon the strength of these faithful renditions, albeit sung not in Spanish but in the band’s Limburgish dialect. Bauer references a fan of the band who suggests Rowwen Hèze’s “local global style” clearly resonates with their audience in ways similar to that of Los Lobos’ playing and performances; while both groups may share similar experiences and socioeconomic backgrounds, along with a love of the squeezebox, Bauer suggests this “seems to create a more appropriate cultural community than notions of common language, ethnicity, and location alone” (236).

Indeed, throughout her book, Bauer strives to assess conjunto as music, rather than through (or separate from, even) its relationship within Texas Mexican cultural practices and working-class identity. In several instances, this approach comes off as reductive, or, worse, dismissive, of the genre’s historical origins as well as its contemporary fans and followers. At its most effective, however, Bauer delivers nuanced, welcomed insights into cultural production and heritage preservation, as well as a detailed examination of the exotification, appropriation, and exploitation that can and often does occur within conjunto’s relationship with mainstream, popular music.

Underlying her analysis is a critique of authenticity. Bauer continually returns to the question of who can—and who cannot—claim inclusion with/in conjunto. If the avant-garde experimentalist, or the dancing cowboy playing country-and-western tinged rancheras, then why not the Limburgish-singing rockers, or the overseas visitors who found inspiration in the music? The process of globalization has expanded the genre’s reach and broadened the stylistic categories, allowing for jazz and rock-influenced performances alongside traditional forms of playing. Yet, even as a model of hybridity, what we may think of as traditional conjunto music nonetheless reflects variations in instrumentation and musicality intimately tied to regional experiences and historical periods. The range of styles and performative repertoires within the genre exhibit a wide range within Tejas alone, far beyond what Bauer seeks to convey, with distinctive variations in playing and even dance styles found amongst bands and their audiences from San Antonio and the I-35 corridor, Corpus Christi and the Gulf Coast, and the Lower Rio Grande Valley; whether or not these examples provide enough of a counterweight to the stylistic consolidation Bauer rightfully identifies having taken place on a global scale through Flaco’s widespread popularity remains debatable.

-Alejandro Wolbert Pérez

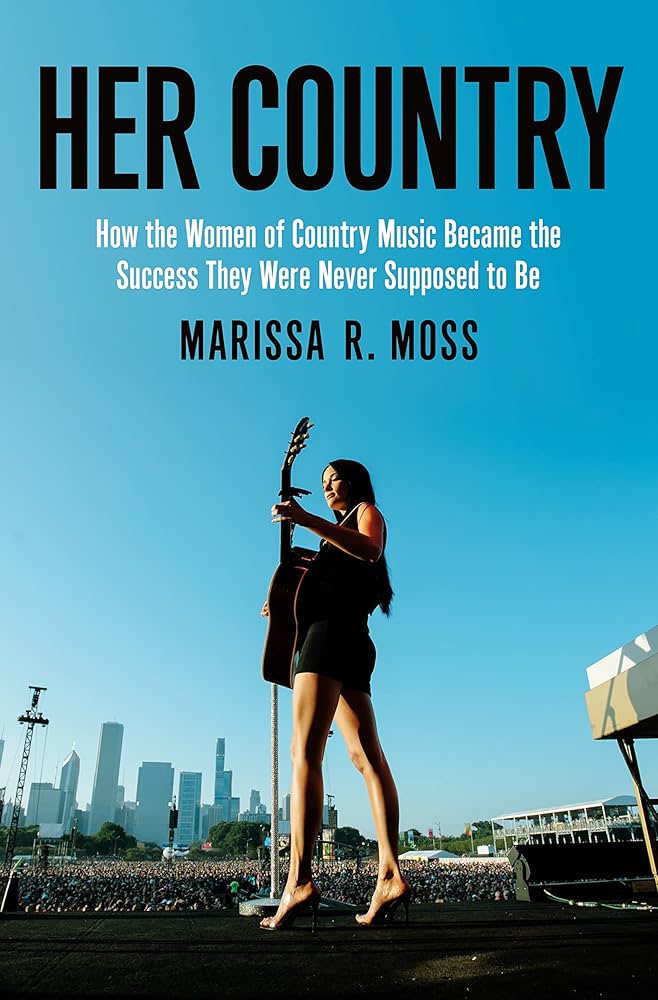

Her Country: How the Women of Country Music Became the Success They Were Never Supposed to Be

By Marissa Moss (New York: Henry Holt and Co, 2022)

Marissa R. Moss’s Her Country: How the Women of Country Music Became the Success They Were Never Supposed to Be Country is a timely journalistic account that contributes significantly to the growing awareness of how the country music industry has purposely pushed musicians of color, white women, and LGBTQIA+ singers and songwriters to the genre’s sidelines. This carefully researched study traces the careers of three prominent female artists, Kacey Musgraves, Maren Morris, and Mickey Guyton, in contemporary country music. What all three have in common is that they hail from the musically diverse state of Texas, where they honed their craft. They came of age in the wake of country radio blackballing the recordings of the Chicks after lead singer Natalie Maines spoke against the Bush Administration’s invasion of Iraq in 2003. And they made the trek from the Lone Star State to Nashville, where they faced the gatekeepers’ amped up exclusionary tactics of keeping country music white and male while tapping into networks of support that fostered their distinct creative visions and commercial visibility.

Moss’s narrative begins in the recent past, explaining why the music of female country artists had disappeared from Billboard’s charts in the early 2000s despite the 1990s star power of so many women, such as Shania Twain, LeAnn Rimes, and Martina McBride. Locating the commercial invisibility of women in a number of crucial commercial and socio-political factors, the author underlines the significance of the Telecommunications Act of 1996, which enabled a single company to own multiple radio stations. This neoliberal consolidation of the radio industry magnified the patriarchal culture of the genre, especially after 9/11 when disc jockeys programmed mainly hypermasculine songs for radio play that, then, succeeded in hitting Billboard’s various country charts. Indeed, the 2015 scandal of Tomato Gate, when radio executive Keith Hill explained that disc jockeys purposely limit the airplay of women’s songs, clearly demonstrates that country’s white patriarchal perspective continues to govern.

Yet, at the same, time, Moss sheds light on the artistic and commercial networks in Nashville’s country music scene that are integral to creating a creative space for women, LGBTQIA+ musicians, and artists of color. As Moss explains, a significant indie underground scene developed in East Nashville at the Hotel Villa, a shabby house with cheap rent where many artists would come to live when they first arrived in Nashville. Referred to as the “Villa Crew,” Moss identifies this “thriving creative class” that emerged in 2008 and made room for “country-adjacent and independent Americana musicians,” and operated independently from Music Row (99, 152). Within this developing environ, songwriting collaborations, performance opportunities, and professional relationships resulted and had a direct bearing on expanding the sound and appearance of the genre. Throughout, Moss documents the pivotal moments when artists of this alternative Nashville scene breaking into mainstream country. Musgraves, for instance, collaborating with queer songwriters Brandy Clark and Shane McAnally in writing “Follow Your Arrow,” a song that acknowledges diverse sexual identities, was awarded Song of the Year by the Country Music Association.

It's important to keep in mind that Moss does not simply locate the commercial success of Guyton, Musgraves, and Morris within the conception of individualistic exceptionalism. Rather she situates their commercial success in relation to not only this alternative Nashville but to a growing infrastructure outside of country radio that has granted visibility to a diverse range of recording artists and songwriters. The author, for example, points to Leslie Fram’s format of “The Next Women of Country” on Country Music Television and Rissi Palmer’s Color Me Country and Hunter Kelley’s Proud Radio, radio programs that highlight BIPOC and LGBTQA+ artists and women musicians.

Yet despite these outlets, Moss continually underlines the misogynoir environment as well as the limits of white feminism that Guyton, in particular, and women artists of color, in general, have had to navigate. But this story ends on a celebratory note with Guyton’s commercial success of becoming the first Black woman to receive the Grammy nomination for Best Country Solo Performance for “Black Like Me” (2021), a response to the police murder of George Floyd from her 2021 album Remember Her Name. While Her Country is a strong rebuke of the racist, misogynistic, and homophobic practices of the country music industry, Moss’s chronicle brings to life the vibrancy of a multivalent milieu in which artists and fans deeply appreciate country music’s ability to embrace musical and cultural diversity and the infrastructure that supports it.

-Stephanie Vander Wel

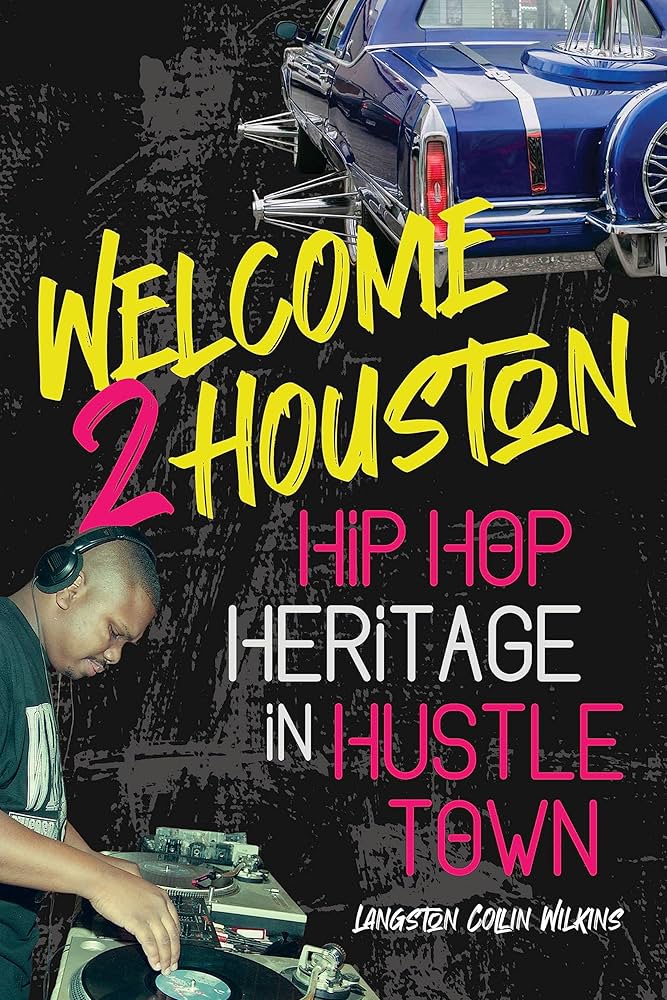

Welcome 2 Houston: Hip Hop Heritage in Hustle Town

By Langston Collin Wilkins (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2023)

“But it’s like this: the South got something to say. That’s all I got to say.” Rapper Andre 3000, one half of Atlanta hip-hop duo OutKast, issued his now-famous declaration at the 1995 Source Awards in New York City. In the face of a loudly jeering crowd, Andre’s defiant acceptance speech for OutKast’s “Best New Group of the Year” award has come to signify a shift in hip-hop’s balance of power: away from its feuding East-West coast epicenters, and towards a new capital in the American South. In some ways, however, that shift had already started; Andre was yet just another messenger. Houston’s rising icon of the city’s singular hip-hop sound—Robert Earl Davis, better known to the world as DJ Screw—had already made his Source magazine debut in an artist interview a few months prior. Screw’s slow-styled influence on the genre, accompanied by new Houston rap stars, continued to rise in the ensuing years. Despite years of resistance, the hip-hop industry was finally taking notice.

In Welcome 2 Houston: Hip Hop Heritage in Hustle Town, ethnomusicologist and native Houstonian Langston Collin Wilkins unpacks the layered meanings of hip-hop identity and heritage in the nation’s fourth largest city. Born as a doctoral dissertation, Wilkins expands on his academic labor—with added content on Houston’s “underground” and Christian rap scenes—to publish his compacted study within University of Illinois Press’s African American Music in Global Perspective series. Like the series in which it lives, Welcome 2 Houston is a labor of interdisciplinary methodologies: employing oral history, musical-lyrical analysis, theories in sound and spatial studies, and an ethnomusicological framework. A self-identified fan of the genre, Wilkins provides an in-depth study of hip-hop music as cultural practice, examining the layered aesthetics of local stylings as the broader manifestations of Black Houstonians’ place-making processes.

Wilkins interviewed more than 25 subjects—rappers and industry folks; mostly young Black men and, glaringly, few women, as he admits—fleshing out a six-chapter study of the city’s manifold neighborhoods tied to hip-hop histories. Highlighting the connections between place, identity, and music, Welcome 2 Houston is patterned on a familiar triad of Black Houston space: the Northside, the Southside, and the Southwest. Rap luminaries from the city’s “sides” typify the most familiar narratives of Houston hip-hop: the Screwed Up Click Kingdom of the Southside; the Northside’s rap institutions, Rap-A-Lot and Swishahouse; and the Southwest as the center point for new-century rap movements with stars such as Tobe Nwigwe and Travis Scott.

Building on theoretical frameworks of space and place, including a nod to French sociologist Henry Lefebvre’s Marxian ideas about social production of space, Wilkins analyzes these residential areas, operating as distinct hip-hop localities—especially in the Northside-Southside turf wars of the 1990s-2000s—as collective representations of Houston hip-hop culture. In them, he finds several through lines of a “pervasive identity.” Emerging as singular topics in chapter studies, Wilkins explores activities that define Houston’s stamp on the genre, including “reppin’ the hood”; customizing candy-painted cars, or “slabs”; and recreational consumption of promethazine syrup, or “lean,” among other social activities associated with “the streets.” Indeed, as Wilkins points out, similar to the genre’s NYC origins, such spatial clashes and distinctions, including the lauded late-1980s South Bronx-Queens borough beefs, typify long-standing traditions in the genre’s hypermasculinized and turf-oriented origins.

While these phrases represent generalized tropes in hip-hop culture, Wilkins interrogates them to discover a deeper meaning in the heritage-making process of Houston hip-hop. In an early section, for instance, he explores how rappers engage in “reppin’ the hood,” invoking street names such as Fondren and Main, or Bellfort and Scott—intersections famously namechecked in popular songs by Houston rappers Z-Ro and Scarface, respectively—to emphasize their sense of locality and identity-making in the hardened, overpoliced, and occasionally violence-plagued areas of the city dissevered from economic and political power. As a foundational example, Wilkins explores the significance of “MacGregor Park,” one of the city’s first rap records, by Houston’s Robert Harlan—a Third Ward native better known by his alias as the L.A. Rapper. Neither from L.A. nor a prolific rapper, “MacGregor Park” was one of Harlan’s two known singles before fading into local obscurity.

A century-old park nestled on the east side of Highway 288, a local freeway forged in the postwar liberal politics of urban renewal, Third Ward’s MacGregor Park was, and remains, a center point for Black Houston life. Harlan’s 1985 electro-hop single, as Wilkins points out, alludes to nearly all major cornerstones of local rap heritage: street name shout-outs, from Griggs to OST; nods to recreational drink and smoke; and the park-hang primacy of customized cars and sexualized young women, or “freaks,” that accompanied them. In later eras, MacGregor Park continued to serve as a central meeting place and public display of customized slabs and trunk-rattling sounds of slowed music—via DJ Darryl Scott’s mixtapes and his famous 1980s Sunday parties at the park, a style later mastered by the Southside’s DJ Screw—as the city’s defining hip-hop sound. It’s a sound that eventually trickled like the stagnant pace of the city’s car-jammed freeways to dominate 1990s-2000s Houston rap.

Delving into a musicological perspective, Wilkins points out that hip-hop’s pre-war blueprint, blues music, immersed in the Black folk traditions of orality and improvisation, also invoked such street-reppin’ themes and lyrics, connecting inner-city Black Houston over generations to the dualities of vibrant life and quotidian violence. Such local examples include the music of midcentury Houston bluesmen Lightnin’ Hopkins and Juke Boy Bonner, the self-described “ghetto poet” of the Northside. Expanding on this, it would be interesting to comparatively analyze Bonner’s lyrics next to Willie D, famous Northside rapper and ex-Geto Boy, both of whom depict casual violence in the Fifth Ward, real or imagined, contributing to popular imaginations of the “Bloody Nickel.”

Like any academic study, discipline-specific jargon can sometimes muddle the book’s readability. Brief chapter sections such as “Subcultural Capital” and “Indigenization of Hip-Hop in Houston Streets” feel disconnected rather than providing a clear roadmap for understanding ideas about space, territoriality, racial/residential segregation, and identity formation, etc. Further, a lack of artist diversity leaves something to be desired in a study examining the many spaces of Houston hip-hop. Namely, the absence of Latinos and women, considering the impact of artists such as South Park Mexican or Beyoncé, to name only two of many, in shaping rap (and rap’s mainstream crossover) from Houston. This last critique likely stems from some needed updating from Wilkins’ original decade-old study, including some city statistics that might feel more relevant in current-decade numbers.

Still, however, Welcome 2 Houston accomplishes what many studies on Houston hip-hop music have mostly failed to do: define and explain a shared hip-hop heritage, based on a nuanced study of the city’s built environment and the spatial-racial politics that have defined working-class Black Houston life. And it's everyday rappers, not just celebrities, that receive much of Wilkins’ ink and analysis. Nor has the sacred-secular divide been seriously considered in existing literature, a subject expertly tackled in the book’s final chapter. True, in fact, of most hip-hop studies. Welcome 2 Houston is a welcome and much needed regional hip-hop study from someone who clearly cares about and lives the culture. Often, the most rewarding reads.

-Alex La Rotta