JTMH Volume 24 | The Vietnam War Song Project

The Vietnam War Song Project: A Texas Discography

Justin Brummer

In 1973, Abilene-based country artist Troy Crane released the single “Springtime Down in Texas (Soldiers Last Dream in Viet Nam)” (Oak 35261). In its verses, a soldier dreams of strolling down the streets of Dallas and San Antonio, visiting Tyler with the roses in bloom, and heading to Fort Worth wearing his boots and big white hat, greeting friends with a “howdy,” and then back to Abilene to see his daughter again. But Crane soon revealed the reality:

I know I’ll never see Texas,

Have my little girl to hug me tight,

Cause I’m 65 miles north of Saigon,

I was only dreaming last night,

Hit in the chest with bullets,

Left here for dead on the ground.

By that same year, the United States government had signed a peace treaty with North Vietnam and withdrawn its remaining forces. They had been present since the Eisenhower presidency in the 1950s and had reached a peak of 543,400 in April 1969. The US service personnel death toll had reached 50,000, while various studies estimate over a million Vietnamese had died.1

The Vietnam War dominated world politics in the 1960s and early 1970s, influencing policy and diplomacy during a key period of the Cold War. This was also a time of major cultural change, impacted by the war, with references appearing in books, film, television, theatre, comics, and art. Popular music, in particular, reflected this change. On June 4, 1966, Billboard reported, “Few conflicts have evoked such a spate of musical production,” and that “since January, well over 100 Vietnam records have been released”.2

This essay forms part of the Austin-based Vietnam War Song Project (VWSP), an archival effort that offers an interpretative examination of every song relating to the Vietnam War.3 The breadth and scope are unique, including more than 6,000 songs identified to date, and examines under-represented areas of Vietnam War music from North America, Vietnam, and across the world.

The author of this article founded the project while working on his PhD in political history that covered the Nixon era of the Vietnam conflict. Inspired by the pervasive way the war is entwined in popular culture up to the present day, the author sought to collect all the songs created about the war. The goals of the project are, first, to collect key data, including genre, location, race and ethnicity, nationality, language, and period of the recording and artists, in order to reveal the many ways people were affected by the war. Second, to critically analyse the song lyrics, exploring the different historical, social, and cultural themes. Third, to build a physical and digital archive—collecting the physical music, including vinyl, cassette, CD, and video, and converting this media into digital form—creating a free, open, and accessible digital online archive, and thus protecting these vital cultural heritage materials.

The project offers a complete picture of the war in song, providing scholars, students, and the public with a unique resource. Embedded in the cultural architecture of war and society, Vietnam War music is a significant historical object of the 20th century. This piece will explore the key songs and themes related to Texas, revealing the state’s experience and engagement with the conflict.

Texas played a vital role in the development of popular culture representations of the war through a significant volume of songs, featuring prominent musicians across genres and covering key topics of the day. As stated In Billboard’s 25-page Texas spotlight from 1973, Bill Williams notes the state “has produced probably more raw talent in the way of artists, writers, producers and other categorized citizens of the music industry than any other state.” Williams went on to explain that there is “more motion in Texas on a Saturday night than in the trade winds of the various seas… They dig jazz… They idolize country… It has become a mecca for rock…and its Latin music is an art form of its own.”4

Furthermore, in Texas, the prominence of military bases, training, war production, enlistment, and political leadership ensured that the Vietnam conflict played a significant part in politics and culture. Thousands of soldiers from across the country were stationed and trained at well-known bases in Texas, including Fort Hood, while 95 percent of all helicopter pilots in Vietnam trained at the Primary Helicopter Center at Fort Wolters.5 US president Lyndon B. Johnson (LBJ), born in Stonewall, played a critical role in the development of the Vietnam War, and became a focus of media, political, and cultural attention, including dozens of songs. He even spent 490 days, nearly a quarter of his presidency, at the LBJ Ranch, dubbed the “Texas White House.”

With its large population, Texas also played a key role in fighting the war. With 2.7 million Americans serving in the Vietnam War, a 2021 Texas Workforce Investment Council study found 414,023 Vietnam veterans from Texas.6 According to National Archives statistics, Texas had one of the highest casualty rates, with 3,415 Texans dying in the war.7 Moreover, Texas continues to have a significant military culture, with the second largest veteran population behind California, standing at 1.4 million, or 6.5% of its population as of 2019, of which over 35% are Vietnam veterans.

As one of the dominant musical centers in the US, and with a significant military culture, Texas produced more than 300 Vietnam War songs that stretch across country, blues, soul, garage rock, contemporary folk, and Mexican American music. These songs reveal a musical battle raging between the anti-war and the pro-government sides. But a closer look at the recordings identified by the VWSP also shows many sub-divisions between these two camps, untouched in the current literature on the war. This piece will explore these changing cultural perceptions of the Vietnam War though the rich musical history of Texas.

Country Music

Texas has been one of the dominant influences in the development of country music alongside Nashville, from Western swing pioneer Bob Wills to prominent figures from the 1970s outlaw country movement such as Waylon Jennings and Willie Nelson hailing from the Lone Star State.

Most Texas country war songs during the core years of 1964 to 1973 presented patriotic content. While anti-war songs in the contemporary folk and rock scene have received much attention in the media and in scholarly works, over 700 pro-war, patriotic, and anti-protest songs were released in the US across all genres, primarily in the early stages of the conflict. Opinion polls for most of the war showed vast support for presidential policy, especially across the Midwest and South, where country music dominated.8 However, from the late 1960s, with an increasing death toll, high economic cost, and reports of military failures (such as the 1968 Tet Offensive), mass public opinion started to turn against the war. As it became less unpatriotic to publicly criticize the war, a degree of anti-war sentiment started to appear in country songs.9

Patriotic, anti-communist, pro-soldier perspective: “It’s for God and country and you, Mom”

Honky-tonk pioneer Ernest Tubb, born in 1914 in Crisp, 40 miles southeast of Dallas, summed up the patriotic position in the title of his 1965 single: “It's for God, and Country, and You Mom (That's Why I'm Fighting in Viet Nam)” (Decca 31861). The narrator focuses on national pride and religion, using the flag as a symbol: “I'll still see Old Glory there, proudly rippling in the air, the same blessed flag that is watching over you.” It charted on Billboard for two weeks, peaking at number 48.10 The flag was used as a patriotic symbol to express support for the conflict in Vietnam, referenced in hundreds of songs from across the US, both well-known and obscure.11

Tubb’s song was composed by another Texas country legend, Red River Dave (real name David McEnery), who released his own version. Born in 1914 in San Antonio, he was known for his topical country songs and tributes on subjects from Patty Hearst to Marilyn Monroe and James Dean. He also released a string of Vietnam War songs, all containing patriotic, anti-communist, and religious sentiment, including “Keep That Star Spangled Banner Waving Somewhere” (Reveal R-10-67, 1967).12

Multiple artists framed the war in terms of a fight for freedom and defending US values, as summed up by Hank Thompson, a prominent honky-tonk and Western swing artist born in Waco in 1925. His song “I’m Gonna Practice Freedom” (Capitol 5344, 1965) argued that “many have died so that we might live.” Popular singing cowboy Stuart Hamlin from Kellyville, Texas, recalled John F. Kennedy’s 1961 inauguration speech, seen as a call to action for the greater good, with the single “What Can I Do for My Country,” in which the narrator notes “the valiant men who fought and died to keep our country free” (RCA 74-0525, 1961).

Two Texas songs present the perspective of women back home who accepted the absence of their partners, justified by the fight for freedom. Lois the Blue Lady, out of Mesquite, performed “While Your in Viet Nam” [sic] (Jamaka 640J-3688, 1965). She sings, “I know that you must go . . . freedom for all.” Janey Hart & Olin Berry from Austin released “Vietnam” (Back Forty 45-6813, no date, hereafter ND), arguing that “freedom’s price is never cheap” and that in Vietnam “aggression must be stopped, we have to draw the line.” These sentiments echoed later in songs about other US foreign interventions, such as Afghanistan and Iraq, and, for example, Toby Keith’s “Courtesy of the Red White and Blue: The Angry American” (DreamWorks 13905-2, 2002), discussed below.

In another family perspective, Mrs. Dorothy Gorman of Fort Worth, the mother of a soldier fighting in Vietnam, released “Happy Birthday, Son” (Sound Town 500, 1968). The singer sends wishes to her son Gerald Wayne Gorman. Gorman said that when she felt down about her son being away, she remembered that he was there “to fight for your country, the land of the free/to make it a better place for you and me,” and thus “I am proud of you son.” The Associated Press covered the story, reprinted in local publications such as Bryan, Texas-based The Eagle, which noted, “Because he observed his anniversary in Vietnam, a Texan at war is having his 21st birthday greetings broadcast over radio stations to thousands of listeners.” According to the article, “Texas broadcasters tried the record on the air and soon a national record distributor made an offer to distribute.” It was reissued on the Hollywood-based national label Tower Records (391).13

Rodeo Jim Peters, born in Oklahoma in 1934 but based in Kirbyville, Texas, a rancher and prominent rodeo cowboy in Southeast Texas, presented the pro-soldier patriotic position from the perspective of a soldier fighting in the war in “G.I. Sam in Viet Nam” (Mountain 1051, ND).14 His buddy from Texas was dying in a foxhole, his “blood flowing for you and me,” and asked him to take a message to “my home in Texas, where my mother waits for me.” The dying soldier requested that his parents “take my spurs and saddle from the peg upon the wall/For I will not be returning for the roundup.” To his sister, he sent the message: “Her brother is a Texan, and not afraid to die.”

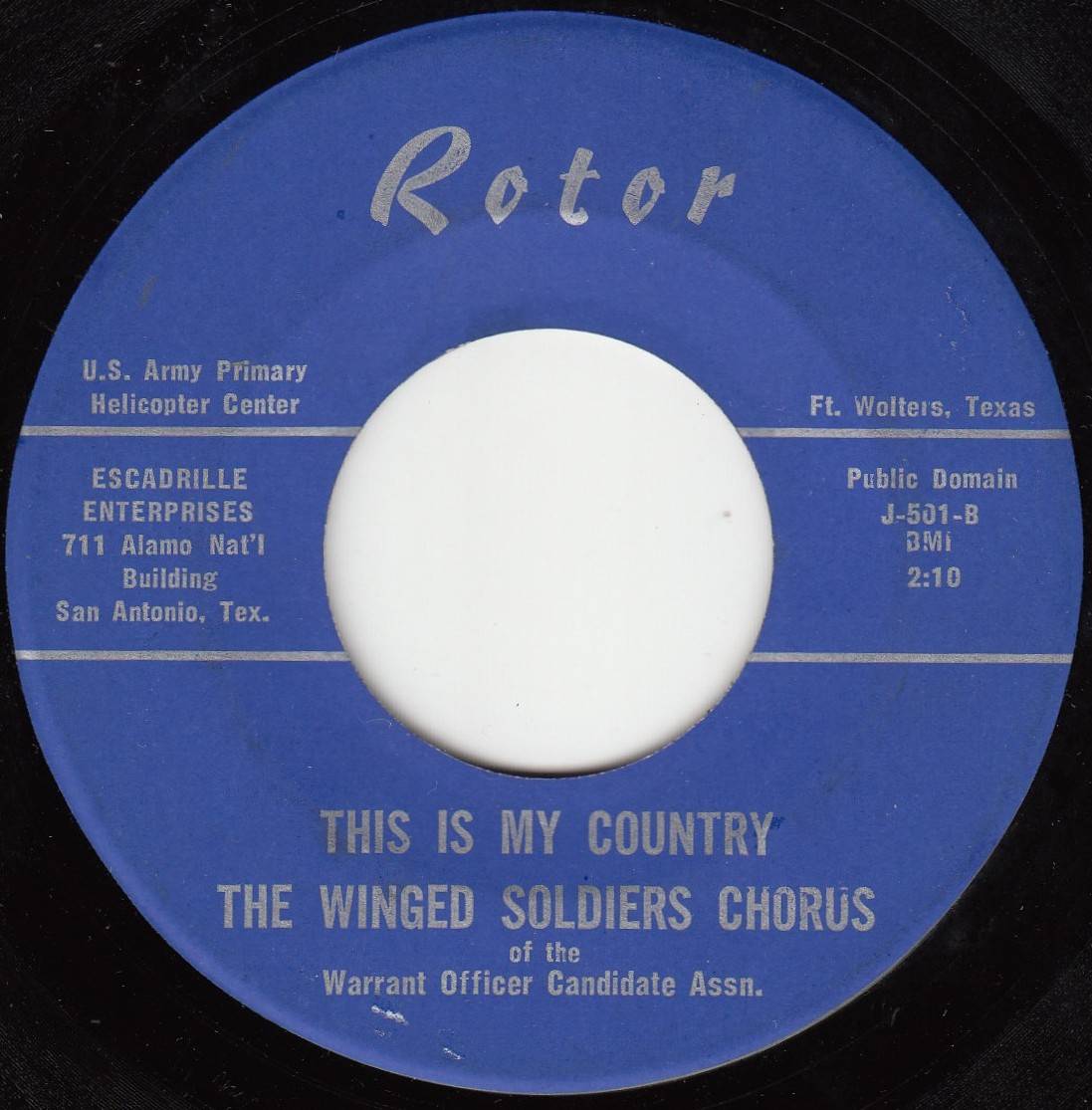

Unsurprisingly, many songs emphasize the perspective of those fighting the war. Advances in technology including the portable tape recorder produced hundreds of songs on tape from US soldiers in Vietnam (“In Country”) or recently returned to the US, on a level never seen in previous conflicts.15 Most songs dealt with army life, furloughs, missions, visiting the Saigon bars, and loyalty towards their country and fellow soldiers. PFC (Private First Class) Dale S. McWright from Dallas released “My Brother” b/w “The Marine Hymn” in tribute to his brother PFC Edward McWright who died in Vietnam on November 15, 1966. He recalls receiving the telegram: “I’m sorry son, your brother’s dead.” McWright declares that his brother “fought for his country . . . that’s why I’m here.” After recording this song, he returned to Vietnam, and was also killed in action, during the Battle for Hue, on February 17, 1968, receiving the Bronze Star Medal.16 Meanwhile in the US, the Winged Soldiers Chorus at the US Army Primary Helicopter Center at Fort Wolters released the patriotic country/fanfare single “Winged Soldiers” b/w “This Is My Country” (Rotor R-001, 1966), which highlights the prominence of Texas, with thousands of trainees and soldiers based in the state before heading to Vietnam.

Another common theme of the patriotic country genre was referencing previous conflicts as a symbol of continuity of patriotism and justification for doing one’s duty. Dee Mullins, from Grafford, Texas, released “War Baby” (SSS International 707), about a baby born during World War II, growing up in the Vietnam War era. He says: “In 1942, 43, and 44, our country was fighting in the Second World War,” and then onto Korea: “In 1951, 52, and 53, there were people being denied their freedom,” followed by Vietnam: “Now in 1967 . . . another defenseless country is fighting for their land.” At the end, he poses the question: “War baby, are you ready to go?”

This theme continued in presenting the continuity in fighting communism, and protecting an independent, non-communist South Vietnam. Buster Doss, born in Jefferson, Texas, in 1925, noted World War II, Korea, Cuba, and East Berlin in “Looks Like We’re Gonna Fight Again,” released in Waco (Wizard 1654, 1962). Doss warns against “lots of puppets, and old Moscow pulls the strings.” The song “Bound in Chains,” produced in Odessa and performed by Gene and The Lackeys, notes “people . . . have the right to be free” from “godless men.” The Big Texan and his Cherokee Tophands from Temple released the single “The Viet Nam Story/Marines to the Rescue” (Big Five 6652, ND), which highlighted the story of a young South Vietnamese girl as told by a US soldier who says, “I’m needed, part of a mission to free her people.” These Texas country songs provided a key representation of the patriotic, pro-government, anti-communist, and pro-soldier perspective found throughout the US, particularly in the South and rural heartland, and country music scenes.

Anti-protest perspective: “Love it or leave it”

A key representation of the anti-protest theme came from Capt. Kris Kristofferson, born in 1936 in Brownsville, who served as a helicopter pilot in West Germany. He composed the song “The Viet Nam Blues” (Dot 16766, 1965), performed by Jack Sanders. On August 28, 1965, Billboard reported that "Capt. Kris Kristofferson, 23, of Texas, a Rhodes scholar, got out of the army recently… Kristofferson's first to be recorded is ‘The Viet Nam Blues,’ a talking single done by Jack Sanders on Dot Records. It is in the patriotic vein, supports the US position in Viet Nam.”17 The narrator, a soldier on leave in Washington DC, encounters a "strange looking bunch" of protesters who are gathering signatures to send a "telegram of sympathy…to Ho Chi Minh.” This caused the soldier to feel "down right sick,” as they seemed more concerned with the suffering of the Vietnamese than the American soldiers and their families. In the final line, the soldier heads to a bar, as the listener discovers that he was "on orders to Vietnam" with only "an hour" before his flight left. Kristofferson concludes, “I don't like dying either, but man, I ain't about to crawl.” With a strong focus on an anti-war demonstration, Kristofferson expressed solidarity and loyalty towards the soldiers while a war was ongoing, and thus a key anti-protest representation, a position that Kristofferson would significantly amend over time.

This anti-protest theme featured in many songs across the US and Texas, and was often combined with anti-hippie rhetoric criticising youth movements, protest rock and folk musicians, drug use (e.g. LSD and marijuana), men with long hair, and clothing associated with the counterculture. Born in 1942 in Lubbock, prominent singer-songwriter Mac Davis, a crossover artist known for country pop, recorded “I Protest” (Capitol 5554, 1965). Davis states, “I protest against you protesters cause you're too blind to see/that you’re only conforming to non-conformity.” Don Bowman, also born in Lubbock (1937), released “The San Francisco Scene” (RCA Victor 47-9576, 1968). Bowman tells his audience that the “hippies are all pouring in” and that they “brought their favourite protest sign” for “a riot every…night.” He notes, too, “they never shave and seldom ever bathe” and “look like they stepped out of the pages of Esquire into a garbage truck.” Jerry Hewitt warned against “Violent Demonstrations” (Music Mill MM-1015, ND), released in Fort Worth, while Dewey Thornton, out of Midland, argued in “Seeing Is Believing” (Dewco DR-1011, ND) that there was a “tidal wave of complacency” as he observed a demonstration, with “bums and unbelievers” who were “burning the red, white, and blue.” Mike Oatman, born in 1939 in Marfa, released “These Are the Times We're Living In” with Terry Burford (Kanwick HFCS 125, ND), which attacked hippies and demonstrators while “several thousand soldier boys who give a damn fight for freedom in Vietnam.”

Meanwhile, Ernest Tubb put out the single “It’s America (Love It or Leave It)” (Decca 732632, 1970)—a popular slogan often seen and heard from the pro-government/pro-soldier side. He sung that he was “tired of seein' hippies runnin' wild” and that “things are gettin' out of hand when you read about a man who'll burn his draft card.” Johnny Mitchel, out of San Antonio, released “Letter to the President” (Tear Drop 3085, 1966), noting “the fools, the beatniks” that “carry around a protest sign” and “burn their draft cards.” These Texas country songs emphasized opposition to demonstrations, draft card burning, and hippie culture, and called for loyalty to the US soldiers and support for government policies.

Anti-war sentiment: “The war is just a waste of time”

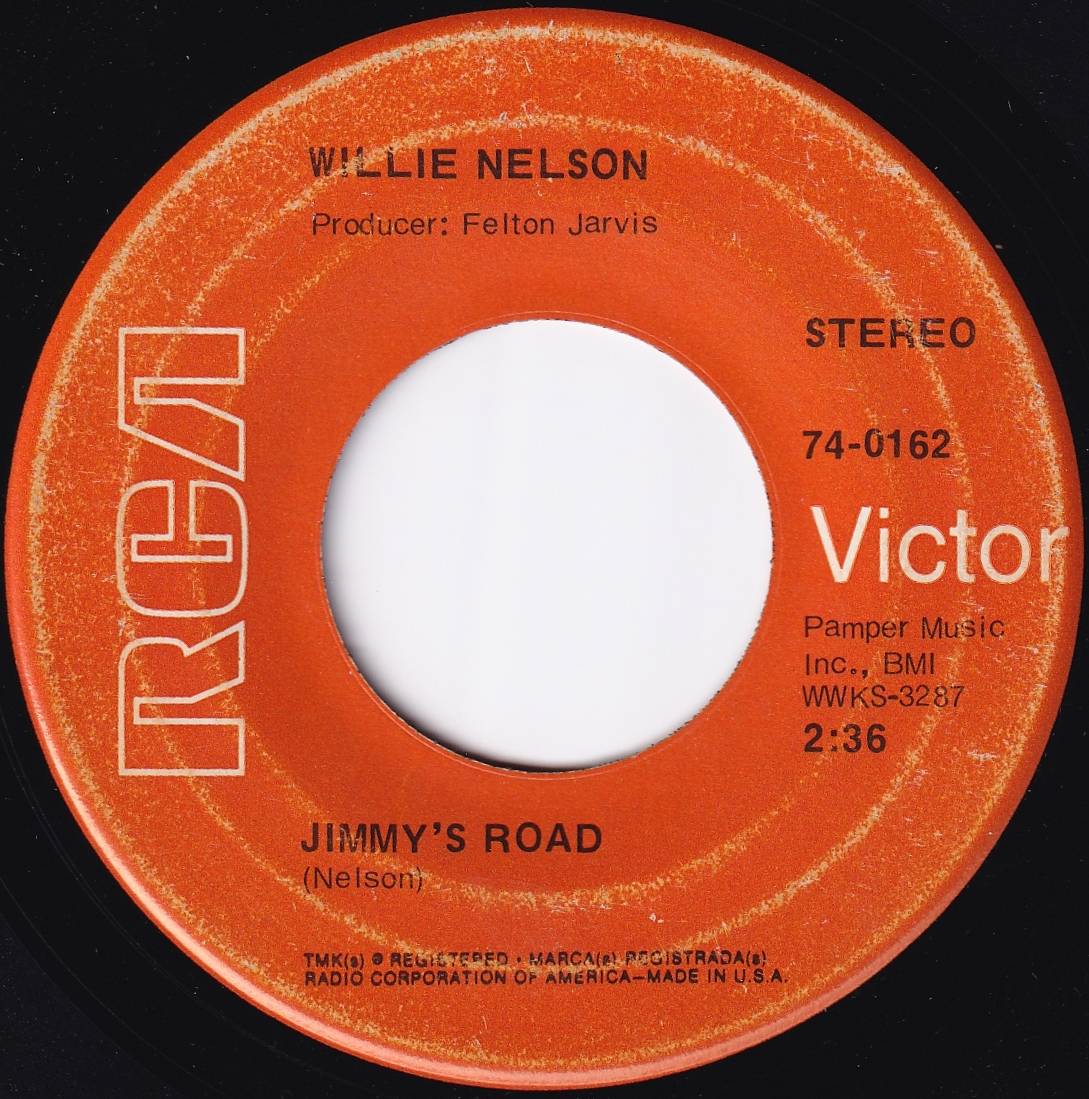

By 1968 the tide was turning in mass sentiment on the war across the United States, and sprinkles of apathy could be spotted in the traditionally conservative country music landscape, with more anti-government and anti-war lyrics appearing. In 1969, Abbott-born Willie Nelson, a then RCA-signed, Nashville-based country songwriter, put out the single “Natural to Be Gone” (RCA 74-0162) which contained on its B-side his obscure song “Jimmy’s Road,” a haunting poem on the devastating impact of war on a community:

This is Jimmy's road, where Jimmy liked to play…

This is the battle ground, where Jimmy learned to kill…

This is Jimmy's grave, where Jimmy's body lies

The beautifully composed and mournfully performed song was a prelude to the singer-songwriter legend to come. Nelson, of course, moved back to Texas in the early 1970s, first played Austin’s Armadillo World Headquarters in August 1972 as America’s ground combat role in Vietnam came to a close, and revolutionized Texas country with his outlaw stance. By 1973, Billboard declared: “In Texas, Willie Nelson is country.”18 Composed in 1968, “Jimmy’s Road” came during one of the most turbulent periods of the war with over half a million Americans stationed in Vietnam and LBJ’s brutal bombing campaign of North Vietnam. The Tet Offensive in January that year had shattered the Johnson Administration’s portrayal of the war, contributing to a credibility gap, with media coverage disproving the government line. It was becoming less unpatriotic to criticise the war and government policy, and war lyrics started to reflect this change. Yet, the country music market overall continued to be deeply conservative, and “Jimmy’s Road” stood out for its negative depiction of the conflict, and its representation of how the significant toll and loss of life was penetrating society and communities.19

Earlier examples of anti-war country songs are scarce. Influential singer-songwriter Roy Orbison, born in Vernon in 1936, released "There Won't Be Many Coming Home" (MGM K13760, 1966), a song originally about the American Civil War, for his film The Fastest Guitar Alive. Orbison said: “it's a reflection on all war,” but “people take it as applying to the Vietnam fighting.”20 It looked at the negative impact and loss of life: “the glory is all gone…before you kill another, listen to what I say/ there won't be many coming home.” This song exemplifies a larger trend of artists updating Civil War, World War II, and Korean War songs to reflect the conflict in Vietnam.

In 1970, Dallas-born George Kent released “Mama Bake a Pie (Daddy Kill a Chicken)” (Mercury 73127), composed by prominent country songwriter Tom T. Hall, who had earlier written a string of patriotic, anti-communist songs for other artists, such as Johnny Wright’s hit “Hello Vietnam” (Decca 31821, 1965). Kent’s song is narrated from the perspective of a disabled veteran who says that “since I won't be walking, I suppose I'll save some money buying shoes,” and recalls that his girlfriend has left him: “she wrote me, said goodbye, she couldn't wait.” While noting that “they say the war is just a waste of time,” he sarcastically sings, “yes sir, it was worth it for the old red-white-and-blue,” thus leaning towards an anti-war perspective.

Similarly, a string of country songs implied that the war had gone on long enough, including many from Texas. Gordon Baxtor, of Port Arthur, released “Why Must the Brave Die Young?” (Spindletop SR-0016). Oneda Harding released “Peace in Viet Nam” (Texas 2094, ND) in Waco, while the narrator of Earl Epps’s “4a.m. in Viet Nam” (Stoneway 1016, 1970), released in Houston, is a soldier who writes a letter to his mother and says, “things don't look too good over here in Vietnam,” and that he heard the politicians are trying to gather “around a big conference table/to talk of peace and to end this war.”

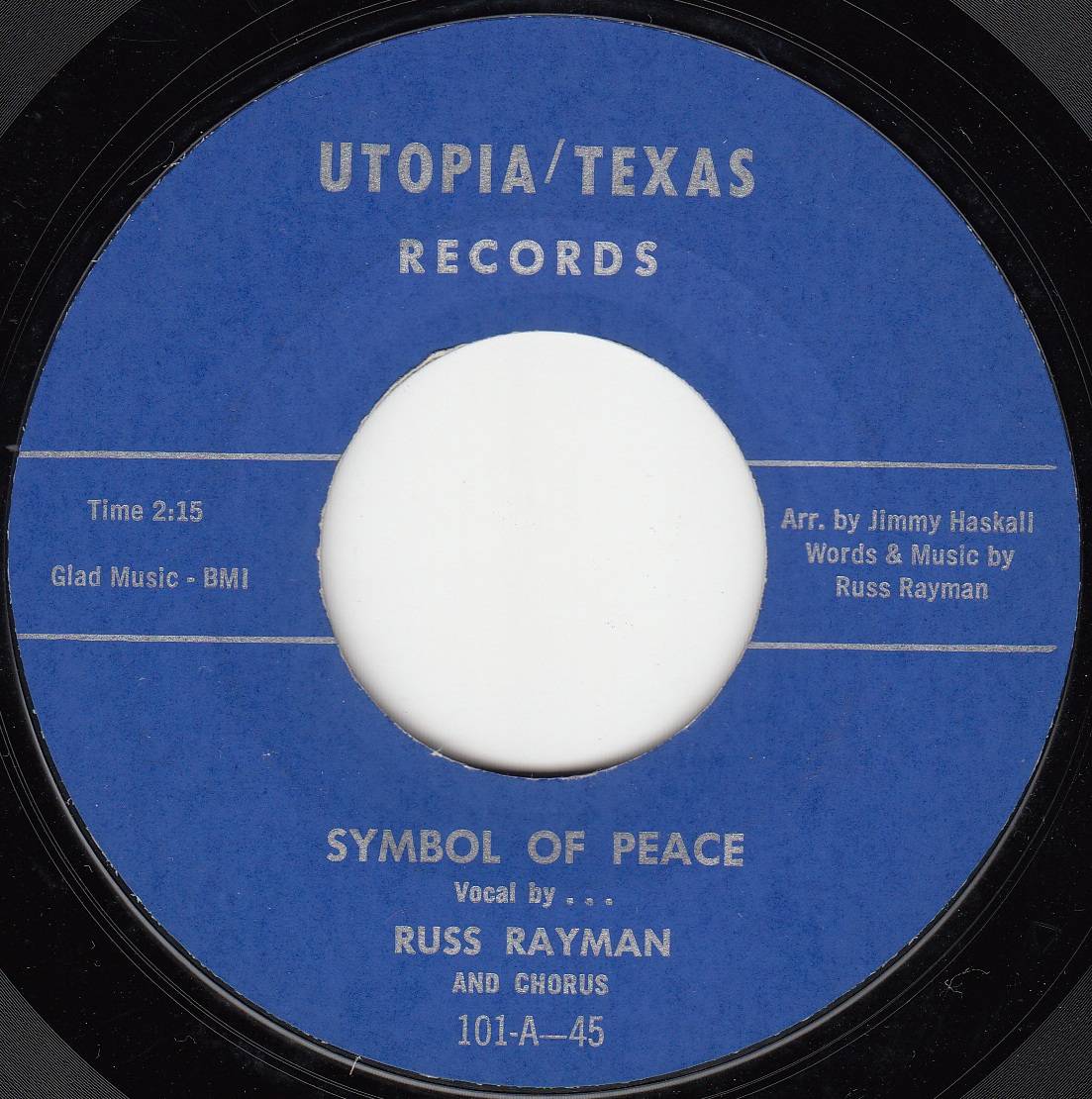

Dallas’s Larry G. took a blunt approach in “He's All Dressed Up in His Red, White and Blue” (Tex-Tone L-500, ND), declaring “let’s end this war/and bring all the boys home to stay.” Russ Raymond released “Symbol of Peace” b/w “Are We Really Civilized” (Utopia/Texas 101, 1968) to raise funds for the Progressive Peace Party in Utopia, Texas, for the 1968 presidential election. The party ran adverts in local Texas newspapers calling for an end to “the senseless slaughter of America’s youth…in some remote jungle.” It claimed that, “the root of evil is right here in America…brought about by our chronic war economy,” and thus people need to demand “an end to the Vietnam War.”21 Meanwhile, Michael Pietzsch presented his protest perspective through showing support for Dallas anti-war activist Stoney Burns, who edited the counterculture magazine Dallas Notes, focusing on his harassment and arrest, which was rumoured to be linked to his public criticism of the war, in the song “Ballad of Stoney Burns” (Red River 0001, 1972).

While fewer in number compared to the patriotic songs released in the country music genre, these tracks indicated a change in perspective. In addition to well-known Texas artists such as Willie Nelson and Roy Orbison, prominent country musicians across the US, including Johnny Cash, Arlene Hardin, the Wilburn Brothers, and Skeeter Davis released records with anti-war sentiment in the late 1960s, a reflection of the changing attitudes towards the Vietnam War.

Pro-soldier & Anti-war: “Nailed Lt. Calley to a tree”

One of the most controversial events of the war was the My Lai Massacre, which inspired over 150 songs in all genres from across the US during the war and post-war years.22 The prominence of the issue and its extension into the music industry even generated a Billboard headline on April 17, 1971: “Calley Disk Stirs Market; Supply Runs Behind Demand.”23

Between 300 and 500 civilians were murdered in the South Vietnamese area known as "Pinkville,” containing several hamlets such as My Lai 4 and My Khe 4, and throughout the area of Song My, by US forces on March 16, 1968, under platoon leader Second Lieutenant William Calley. Calley was subsequently tried in the United States for premeditated murder and took the line that he acted under orders, pleading not guilty.24 Most of the songs released from 1969-1971 were in the country music genre and supported Calley, yet several also contained anti-war sentiment, displaying an interesting mix of pro-soldier and protest songs. Public opinion polls showed significant support for Calley yet coincided with a period when a majority of people supported withdrawal from Vietnam or thought the war was a mistake.25 Thus, the song highlighted that people were protective of soldiers and veterans during war time, especially in the country music genre, and in Texas, which produced some of the key responses to the massacre.

One of the first records released about My Lai in 1969, shortly after the atrocity became public, was from country artist Big Bill Johnson, based in Greenville, 50 miles northeast of Dallas. His song "Set Lt. Calley Free" (REM 45-467) argued that the US was a “sick society,” as it had “crucified” and “nailed Lt. Calley to a tree,” presenting Calley as a sort of Jesus figure, wrongly accused and charged. Yet the song displayed resentment towards the lengthy war: “We Americans are tired of a war that can't be won.” Matt McKinney recorded “Ballad of My Lai” (Danrite DR-115, 1970), which blamed the massacre on the politicians, military, and society: “we sent him into the battle” and “placed the gun in his hand,” absolving Calley of responsibility, a soldier doing his duty in “a war we could never win.” The theme of Vietnam as an “unwinnable war” has become a strong contemporary reading of the conflict, as reflected by modern artists including the Woodlands’ Hayes Carll (addressed later).

Bill Bailey, a former Harris County constable, radio DJ, country artist, and longtime announcer at the Houston Livestock Show and Rodeo, released “Indictment of the Nation” (Westpark 6980, 1971) which strongly supported Calley for doing his duty, with a dig at the protest movement: “Bill Calley didn't wait around, dodge, and protest” and “Uncle Sam looks sadder now and weaker” because of the trial. Yet, Bailey notes, “He didn't like the winless war,” revealing how this view had become so widespread even in pro-government, patriotic circles. Surprisingly, the distribution company decided to invest in running a full-page advert in Billboard on April 17, 1971, to drum up sales of this single, claiming, “It is the record most in touch with the current national mood.”26

Jimmy P. Sims from Henderson, Texas, who released “Ode to Vietnam” (Music by Mark 1-2003) in nearby Longview, praised Calley for his willingness to “fight and never ask why,” claiming that “a VC woman and her children carry guns” and pleaded to “set William Calley free,” yet concluded the song by repeating the line “please stop the whole war in Vietnam.”

Many My Lai songs in country music took the opportunity to reinforce their patriotic opinion on the conflict or just show solidarity with the soldiers. Mutt Cottingham’s “Free Calley” (Keepsake KS1010, 1971) from San Angelo argued that “justice was shattered when this senseless trial begun” and that Calley had “fought to win/this war's deadly game.” Country artist Johnny Nelms, also a former Texas State Representative from Pasadena in Harris County, condemned the conviction of Calley in 1971 during the 62nd regular session of the House of Representatives.27 Nelms then released the song “Lieutenant Calley” (Bagatelle 4271, 1971) in Houston, arguing that “everybody knows the American way . . . Calley was duty bound to do his best.” Lee Ofman and Wayne Chaney both released versions of the song “Young Bill Calley” (K.O. PMI-101 & 102) in Houston, which contended that Calley “came to serve his country by fighting this war/never hesitated, with a 'why or what for,’” and that society was to blame for sending him to Vietnam. While many of these Calley songs contained US patriotic sentiment, the criticism of the government and the military and opposition to the war found in some of the lyrics reflected the difference between support for the troops and antipathy towards the war itself.

Soldiers and the Home Front: “I clean my gun and dream of Galveston”

Not all country songs from and about Texas took a strong political position. Some considered the perspective of the soldier fighting or those back home on the domestic front. While some contained minor patriotic or protest sentiment, the focus was on relationships, combat conditions, and returning home.

B. J. Thomas, a country pop artist born in Oklahoma but based in the Dallas-Fort Worth area, released “Billy and Sue” (Hickory 45-P-1395, 1966) about a high school couple in love when Billy was sent to war. Sue’s letters strengthened his ability to “fight for his country.” However, Billy received a “Dear John” letter and was later killed in action: “[Billy] didn't die from a bullet, but he died from a broken heart.” Rockabilly artist Bobby Skel, born in Houston in 1942, also focused on the soldier’s perspective, with a narrator who heads out to war and wonders, “Will she forget me while I’m gone?” in the song “Three Candles,” released in Fort Worth (Soft S-983, 1965). This theme was found in a string of country records, including Corpus Christi’s Lofton Kline, who released “My Heart's Not Over Here” on Houston label Soundville (SV-2001, 1971).

One of the most successful country war-themed songs of the era came out of the California country scene but chose the iconic Texas seaside town “Galveston” as its setting. Composed by pop and country songwriter Jimmy Webb, and popularised by Glenn Campbell in 1969 (Capitol 2428), it tells the story of a soldier dreaming of home and missing his partner, and conjures images of US seaside towns and young romance broken by war: “I still hear your sea winds blowing… I clean my gun, and dream of Galveston… Is she waiting there for me, on the beach where we used to run?”

Multiple songs focused on returning home. Buck Biggs released “Going Back to Texas” (Western 1002, ND), with the narrator “stuck in old Vietnam, rain and bullets…pouring down,” when he starts thinking about “Abilene” and the “State Fair of Texas, the best I’ve ever seen.” The good news was that he was heading back: “Texas, I’m homeward bound.” Likewise, Buck Griffin, born in Corsicana in 1923, released the song “From Viet Nam to Dolan” (Foundation 10415, 1967), in which the singer is headed home to be reunited with his partner: “So Mr. bus driver, keep jamming those gears/I ain't seen my baby for about two years.” Grady Owen in “Vietnam Blues” (Helton 102, 1966), released in Irving, took a different perspective, presenting a soldier on his way back to the US who was going to miss the camaraderie of military life: “I'm going to miss my first Sarg and his big mouth/Gonna miss my buddy.”

But others were less fortunate. Bill Gold of Grand Prairie released “Both Sides of the Tracks” (United 195, ND), a song written from the perspective of a child whose mother had recently died, and thus effectively left an orphan because “my daddy is a prisoner in North Vietnam.” This subject appears in more than 160 Vietnam War songs identified by the project.28 Ronnie Lee’s “Soldier’s Letter” (Peake 45-002, ND), released in Abilene, is narrated from the perspective of the P.O.W. who dreamt of returning home and getting away from “this awful prison.” Meanwhile, hundreds of these songs also focus on terrible combat conditions, such as “Out of Sight, Out of Heart, Out of Mind” by Rick Wells and His Vietnam Service Buddies from Houston: “In this war I fight, it's hell on earth” (Odle 103, 1968).

Another popular topic was the Christmas song, as seen with “Santa's Gonna Bring Me Home” (Pic 1 #141, ND) by Houston-based country artist Johnny Louis, narrated from a soldier “here in Vietnam” who reassures his children that he will make it home. Hundreds of Vietnam War songs in all genres used Christmas as a backdrop to show the impact of the war on soldiers and families.29 Hailing from Fort Worth, the Texas Girls’ Choir’s “Come Carolling With Us,” noted on its picture sleeve, “This modern sleigh will not bring Santa to the boys in Vietnam but it will bring a gift from home,” while the El Paso High School Varsity Choir released the single “Vietnam Christmas” (LinJo 112, ND) which sent a prayer to “those who fight and have been wounded in Vietnam.” Literature on the songs of the Vietnam War tends to focus on the divide between hawks and doves. However, a substantial body of songs took a nuanced approach, presenting the life of the soldier and the impact of war back home, some with only subtle political views, providing a more rounded view of the Vietnam War era.

Contemporary Folk & Rock: "Hey, LBJ, how many kids did you kill today?"

The category of anti-war songs, or protest music, has traditionally dominated the Vietnam War song literature. Generating over 700 songs across all genres during the war years, it is one of the core categories of cultural representations of the war.30 Most of these were found in the contemporary folk and rock genres, especially centred around the California and New York music scenes, across the North, and internationally. The Vietnam War coincided with an explosion of teen, garage rock, and contemporary folk movements. With a breakdown in cultural/generational barriers and the politicization of youth, young musicians started to play a role in a growing anti-war movement across the US and the world. Although overshadowed in Texas by the vast influence of country music and other scenes, such as soul, gospel, blues, and Mexican American music (discussed below), Texas produced some key representations of protest themes.

Early 1960s protest songs often came from an idealist perspective, expressing a moral objection to war and the use of American military power.31 As the war progressed, other sources of protest came to the forefront, with an increasing number of protest songs emphasising the war’s length, military failures, increasing death rate, and the economic cost of maintaining a significant presence abroad, as well as domestic issues such as civil rights and poverty. Opinion polls reflected these attitudes; between 1968 and 1969, mass public support for withdrawal from Vietnam increased from 19 percent to 55 percent.32 Furthermore, as attendance at anti-war demonstrations reflected a larger and wider demographic than seen in the early years, views presented from elite opinion makers also changed, in the media and from politicians. In 1968, all the major Republican and Democratic candidates competing for the presidential nomination had a plan to end the war.

One of the pioneers of the early contemporary folk protest movement was Phil Ochs, born December 19, 1940, in El Paso. He often played songs at anti-war and civil rights rallies in the early 1960s and throughout the war, recording more than ten songs related to the conflict, some of which are the most significant songs of the era, including “I Ain't Marching Anymore” (Elektra 45002, 1965), “Draft Dodger Rag” (Elektra 7287, 1965), “White Boots Marching in a Yellow Land” (A&M SP 4148, 1968), and “The War Is Over” (A&M 932, 1969).

In 1964 Ochs released “Talking Vietnam” (Elektra EKL-269) which took a critical view of the US government's objectives—to establish an independent, non-communist South Vietnam: “Sailing over to Vietnam… Training a million Vietnamese/To fight for the wrong government and the American way.” The lyrics of the song first appeared in the New York-based publication Broadside #32 on September 20, 1963, before the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution (August 7, 1964), a turning point in US involvement and major escalation. Ochs composed the song in 1963 and drew attention to a largely unknown issue in the US public eye, displaying an impressive knowledge of Vietnam’s internal politics and criticising South Vietnam’s Catholic president Ngo Dinh Diem for oppressing the Buddhist population. Ochs was viewed by some as an American “puppet,” which represented an early, idealist objection to the use of American power and influence in Vietnam and support for Vietnamese independence.

The protest movement was particularly vocal through demonstrations and cultural output, placing major domestic pressure on the White House and Congress, with the Texan president becoming a major focus point of protest. Over fifty war songs across genres reference LBJ (out of the more than 150 songs in total about LBJ, which also included Civil Rights, the Great Society, and elections).33

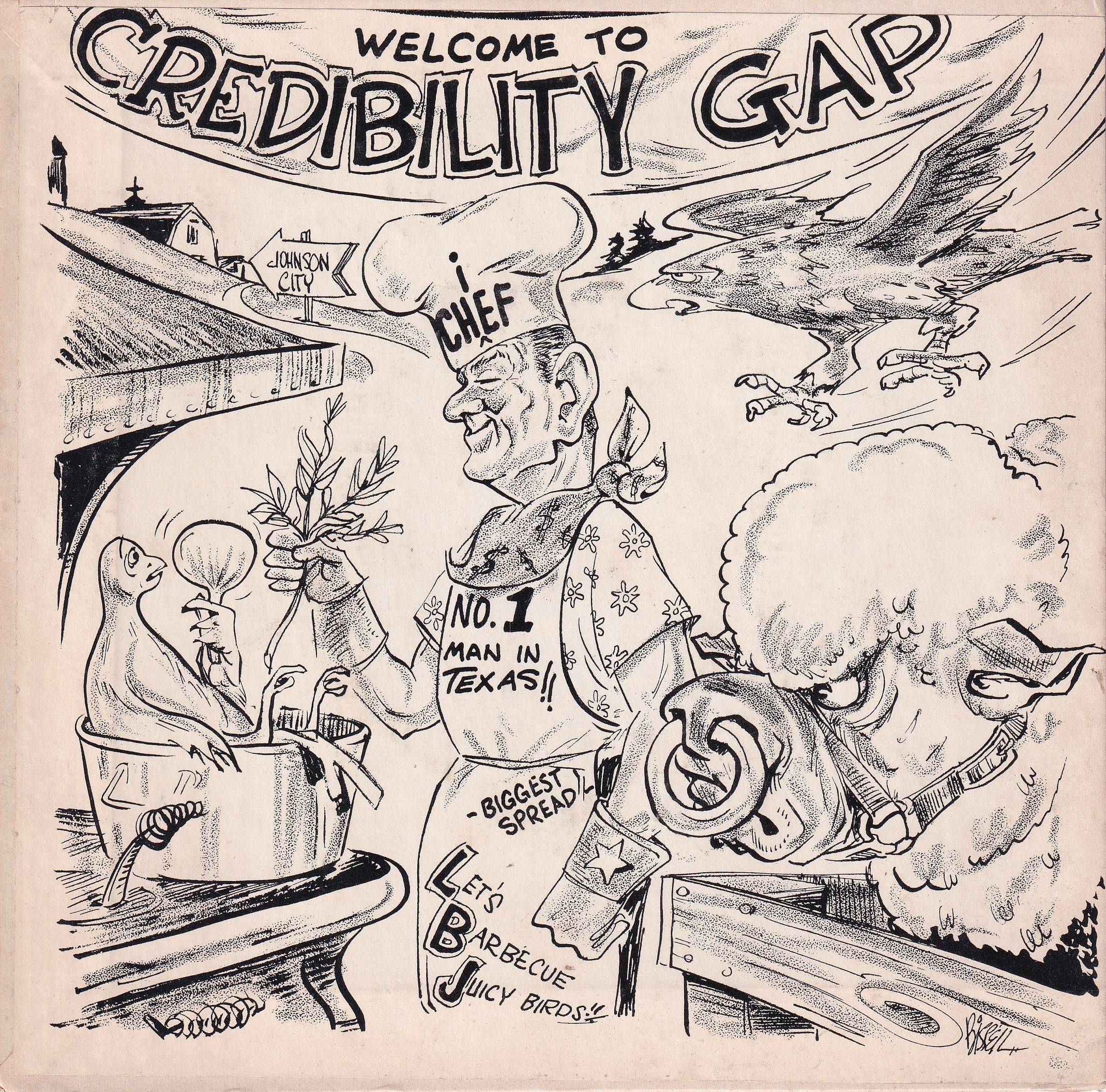

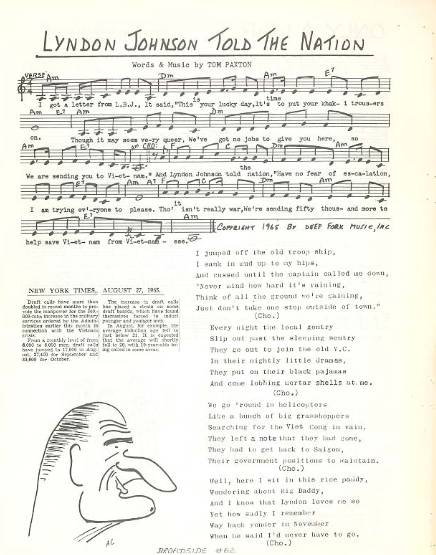

In 1965 Ochs wrote and recorded “We Seek No Wider War,” which addressed the “credibility gap” and scepticism of LBJ’s assertions regarding the progress of the Vietnam War. The title of the song was taken directly from LBJ’s statement on the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, when he assured the American public that despite the major troop escalation, “we still seek no wider war.”34 Although Ochs’s recording was not released at the time, the notation and lyrics were published in Broadside #63 (October 15, 1965), and thus circulated within the contemporary folk scene. The narrator notes “the silent screams of the dead and the dying” while LBJ maintained that it was a limited conflict.35 This was also the theme of the novelty folk song “Welcome to Credibility Gap” (ND, unknown artist), and Tom Paxton’s well-known song “Lyndon Johnson Told the Nation” (Elektra EKL 298, 1965), with its catchy sarcastic chorus: “Though it isn't really war/We're sending fifty thousand more/To help save Vietnam from Vietnamese.”

In 1967 Bill Frederick, prominent on the New York folk scene, released the LP Hey, Hey…LBJ! Songs of the U.S. Antiwar Movement (Crisis LP-001), a collection of 12 anti-war songs. Its title track “Hey, Hey LBJ” repeats the famous chant popular at anti-war demonstrations: “How many kids did you kill today?”, placing the blame firmly on the president. Furthermore, Frederick implicated several American companies that supplied the US government with materials used in Vietnam: “LBJ goes all the way with Dow, GM, and Boeing." Dow referred to Dow Chemical, which produced the chemical weapon napalm, a jellied gasoline mixture. Declared a war crime in 1980, the US government brutally dropped tons of this weapon on Vietnam, inflicting devasting burns on its victims.36 It also produced Agent Orange, the defoliant/herbicide used by US forces, which had long-term negative health effects on the Vietnamese and US soldiers who came into contact with the chemical. Prominent activist and folk artist Pete Seeger presented LBJ as blindly leading the country to disaster: “Waist deep in the Big Muddy and the big fool says to push on” (Columbia 4-44273, 1967). Dozens of songs pleaded with the president to end the conflict, including 11-year-old Dewey Jones in “Please Mr. Johnson,” who asks, “Send my brother home… You said on television it won't be long” (Diamond D-219, 1967).

An interesting anti-war/protest episode featuring Texas, LBJ, and the Vietnam War that generated folk protest songs was the case of the Fort Hood Three, three soldiers who refused to be deployed to Vietnam in 1966, an early example of resistance from within the US military. They were Private First-Class James Johnson, Private David Samas, and Private Dennis Mora, stationed in Fort Hood. Pete Seeger released “Ballad of the Fort Hood Three” which noted that Mora had “cast his vote for Johnson in 1964” but could not follow his orders as “we may have to kill women and children” and “we say this war's illegal, immoral, and unjust.” Additionally, Mora’s sister, Grace Mora Newman, also composed a song published in Broadside #74 (September 1966), “The Fort Hood Three's Answer to the Green Berets,” sung to the tune of Barry Sadler’s patriotic, best-selling song “Ballad of the Green Beret” (RCA Victor 47-8739, 1966).

Meanwhile, the garage rock scene of the youth counterculture unsurprisingly focused heavily on draft and generation gap protest songs, as musicians, partners, and friends faced being sent to Vietnam. Of the approximately 100 songs of this kind, many key examples came out of the Texas scene. Although many opposed the draft and criticised the burden placed on the young, they also contained a degree of anti-communism and patriotism. B.J. Thomas, usually known as a country pop artist, released the garage rock track “Vietnam,” a rare single issued in Big Spring on Joed (TR-119, 1965). The song takes an anti-communist position, but the narrator also resents the draft, noting he is off “to fight for my country in a war that shouldn't be but is necessary,” and to fight against “Russia, Red China, Viet Nam.” The song offers a nuanced perspective, noting that the adults “call us young and reckless kids,” and urging those in power to “stop this war.”

Another rare garage single, “Don’t Burn It” (Brownfield BF-1035, 1966), came from Fort Worth-based garage group the Barons. The song focused on the issue of draft card burning which took place at many demonstrations. LBJ prohibited the destruction of draft cards in an amendment to the Universal Military Training and Service Act in August 1965, and the arrest of David O’Brien in 1966 for burning his draft card led to a Supreme Court Case on the First Amendment (see David Paul O’Brien v. USA, US Court of Appeals), which received much media attention. The song’s narrator receives “a little card that says don't burn,” and he contemplates whether to “fight or go to school.” Again, the narrator highlights generational issues: “Worrying about my generation . . . people take us for nothing but fools.” Likewise, garage artist Jerry Simpson focused on the younger generation in “Young Boy” (A-OK 1053, ND) released in Odessa, which notes, “You’re old enough to learn how to die boy, fighting for your country under foreign skies.”

Michael Blessing (a.k.a. Michael Nesmith), born in 1942 in Houston, later a member of the Monkees, released “The New Recruit” (Colpix CP-787, 1965), a garage folk cover of Tom Paxton’s satirical “The Willing Conscript,” in which a draftee sarcastically thanks the sergeant for teaching him “how to slaughter and to hate the enemy.” In “Military Minor Blues” (Edmark 10020, 1968) by garage artist Michael Merchant from Ingelside, near Aransas Pass, the narrator worries whenever people mention the word “draft” after hearing about the war on the news: “Shut that window dear, I can feel a draft” says his mother, to which he responds, “Don’t say that word, it upsets my mind.”

LBJ became a target of garage bands opposed to the draft. Chuck Blake released “Please Mr. Johnson” (Sing-O-Tek 4177, 1966), in which he urges the president, “Don't make me go, the Vietcong are waiting out there,” as did the Put on Company in “Please Mr. Johnson (I Don't Wanna Go)” (Jest J-101). Henry Flynt & the Insurrections in “Go Down,” recorded in 1966 (Locust 39), called on people to "let Johnson know/You won't fight his dirty wars no more.” Seeds of Euphoria took the comic route in “Let’s Send Batman to Viet Nam” (TMP-Ting 120, 1967). “Are you listening LBJ?… We have found the answer” to solve the Vietnam conflict.

Garage groups surveyed the negative impact of the war and showed support for the protest efforts. The Outcasts, formed in San Antonio, released “Price of Victory” (Askel AK-102, 1966), narrated from the perspective of a soldier killed in action: “I must go again and fight…life seems so very dear…blood is on my green beret,” and the cost “has been high.” Ray Hildebrand from Joshua, Texas, a member of teen pop group Paul & Paula, takes the perspective of a mother whose son returned from the war disabled in “Why Did He Go Away?” (Soft S-98, ND), released in Fort Worth.

In 1968, domestic attention soon turned to the November presidential election. LBJ withdrew from the race on March 31, 1968, but Texans remained in the narrative with demonstrations outside the Democratic National Convention in Chicago in August 1968. This resulted in the arrest of over 600 protesters, amongst them eight prominent activists known as the Chicago Eight, including Black Panther leader Bobby Seale, born in Liberty, Texas, in 1936. Soon after the trial began in 1969, the judge, Julius Hoffman ordered Bobby Seale to be bound and gagged for contempt of court and tried separately, with the other white defendants becoming the Chicago Seven. The event generated dozens of songs dealing with Vietnam and the Civil Rights movement, including “Free Bobby Now” (BPP-4501, 1970) by the Lumpen and “Bobby Seale Bound and Gagged” (Female Fun FF004, 2003) by hip-hop ensemble J. Rawls/The Living Vibe. Additionally, El Paso-born Phil Ochs, who had famously performed the song “I Ain't Marching Anymore” outside the convention, was ordered by the trial judge to perform the song on the stand.37

Richard Nixon won the 1968 election, and the incoming Republican president and his outspoken conservative vice president Spiro Agnew became the new focus of protest, with two key events on the domestic scene particularly raising pressure. The first, the Kent State demonstration on May 4, 1970, protesting the Cambodia incursion, saw four students killed by the Ohio State National Guard, shocking the nation and generating more than 80 songs around the world.38 Singer-songwriter Don Sanders from Houston, known as the “Mayor of Montrose,” was a regular performer at the Anderson Fair Retail Restaurant, a popular folk listening room that attracted the likes of Townes Van Zandt, Nanci Griffith, Robert Earl Keen, and many others.39 Sanders released “Kent State History Play” (Mean'n Low 1, 1972) which cleverly twisted Agnew and Nixon’s attempt to blame the protestors (the “bums” as they referred to them) for starting the violence, suggesting that in fact the administration incited the violence both at home and through the bloody conflict in Vietnam: “Those who turn to violence are the cause of tragedy,” and “Perhaps he'll recognise his own guilt and he'll confess and will kill himself in view of hungry TV cameras.” J.J. Light, an Indigenous American and member of 1960s San Antonio country rock group Sir Douglas Quintet, also sent out a strong warning to the administration on his single “Kent State” (Liberty 15 393 A): “Better stop pushing us around or we'll kick your brains out.” Second, the Pentagon Papers, a top-secret study on the history of the war commissioned in 1967, was leaked to the New York Times by Daniel Ellsberg in 1971, which inspired a string of cultural output. Hard rock group Bloodrock, founded in Fort Worth, whose single “Thank You Daniel Ellsberg” (Capitol 3451, 1972), praised Ellsberg for “all the notes that came from you” and for “scheming out all the schemers.”

As peace negotiations slowly dragged on in the early 1970s, and Nixon continued to expand the war with intensified bombing campaigns, the number of protest songs increased and grew angrier. Singer-songwriter Dennis Linde, born in 1943 in Abilene, composed and performed “Ballad of a Blood Crazed Trained Killer” (Intrepid 75011, 1969) in which the narrator imagines various ways to avoid being sent to Vietnam but is too scared to follow through, and thus he ends up “in the mud way across the sea” where several members of his platoon fired shots at a Vietnamese man who was “dying, and softly speaking a name.” The narrator sadly wonders, “Oh god, was it me” that fired the fatal shot. Far from being “blood crazed,” the narrator was turned into a killer by his government and military. Contemporary folk artist Sid Myers released “Pawns of War” (Hare HA-1520, 1971) in Andrews, Texas, calling on people to think about “the mothers and all the lonely wives, who gave their boys, who gave their lives.” The song concludes: “We’re getting together… Let’s end this war” and send “this word to…the leader of this land.”

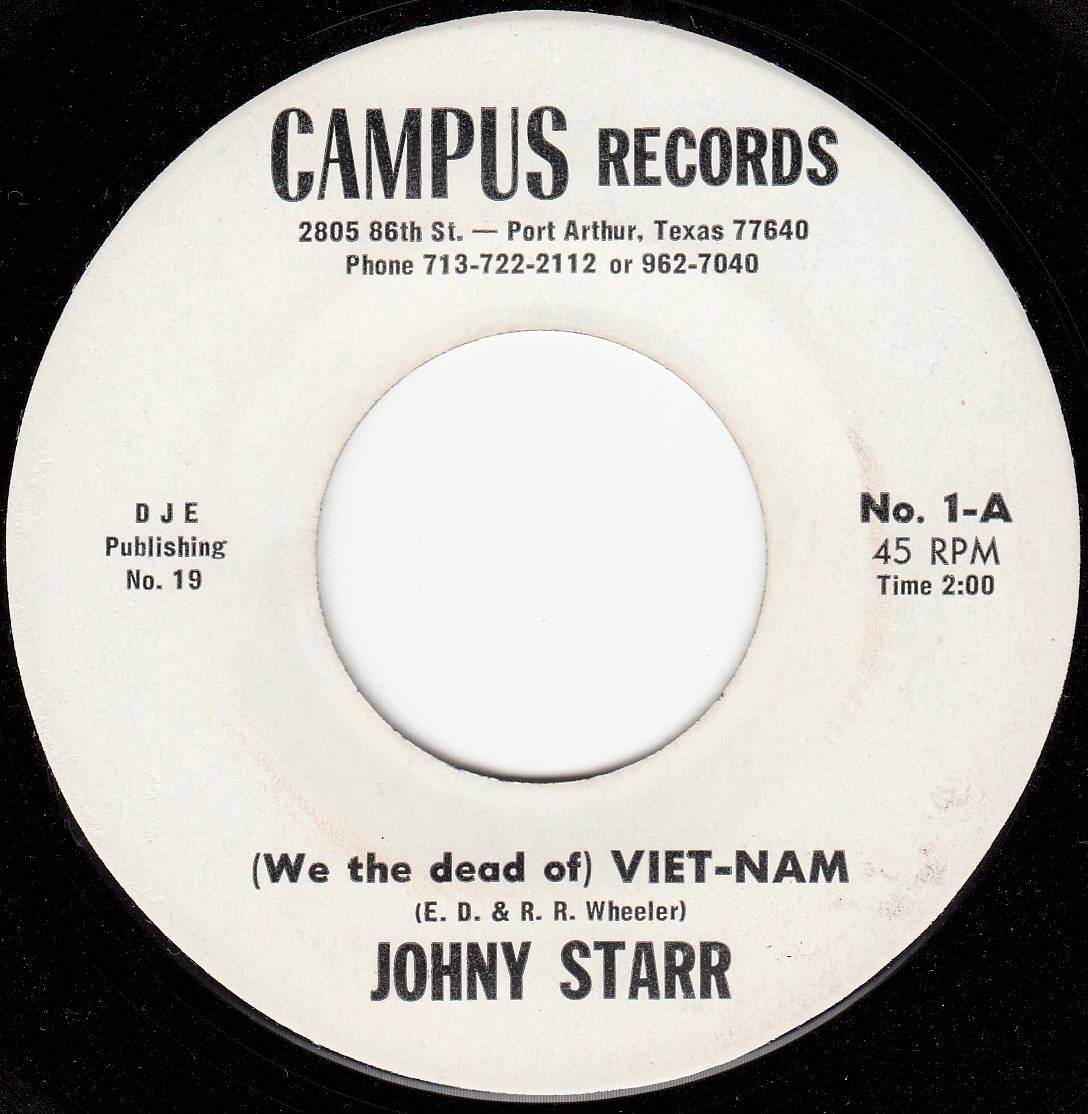

Christian rock artist Larry Norman, from Corpus Christi, released “Great American Novel” (Verve V6-5092, 1972) which asked if the only way to “bring about the peace is to sacrifice your children and kill all your enemies?”. His song “Six O' Clock News” on the same album is narrated from the perspective of a photo journalist who viewed the carnage but could not help: “All those kids without shoes—what can I do?/Napalm tattoos—what can I do?” Additionally, on Norman’s single “Peace, Pollution, Revolution” (MGM 2006 105, 1972), the narrator recalls having “marched for peace in Washington,” and in reference to the 1968 Democratic convention, “gave blood in Chicago.” Folk pop artist Johnny Starr from Port Arthur narrated his song “We the Dead of Viet-Nam” (ND) from the perspective of one killed in action: “All you hear is a number, what an awful shame.” He called on the US: “Please hear our cry, please don’t let others die… Help us stop this awful fight.”

Texas is often overlooked in discussion of contemporary folk/rock songs about the war and the more than 700 protest songs in all genres, both in favor of highlighting the anti-war movement centred on the US East and West coast, as well as the dominance of country music within Texas, which leaned towards the “patriotic” side. But as shown in this analysis, some of the most prominent songs of the era came out of the state or focused on key events and people connected to it, providing a significant representation of the era.

Blues. Gospel, Soul & Funk

Songs from US communities of color provide a complete and nuanced picture of how the war has been portrayed in popular culture, which has been largely overlooked in scholarship.40 AS identified and analysed by the VWSP, African Americans released more than 500 songs in all genres, but especially in blues, gospel, soul, and funk, covering a wide range of opinions and events and from across the US and Texas.41

Blues: "I've got to go kill a brown man for the white man”

In the 1950s, blues had declined in mainstream commercial sales, but the genre found a new audience amongst the early 1960s generation inspired by its anti-war and socially conscious lyrics. Historically, both prominent and obscure blues artists had often composed songs covering topical events, from economic depression to wars and presidential politics. In the sixties, many prominent blues artists turned their attention to the Vietnam War, with more than seventy songs from across the US identified by the VWSP. Texas, as one of the major regional hubs of early blues development alongside the Deep South states, saw a rise in the 1960s of many blues clubs, especially in Austin, Houston, and Dallas.

While a significant number of songs focused on anxiety about the draft and fighting the war, many contained concern for domestic political issues, including Civil Rights, LBJ’s policies, and the role of African Americans in the armed forces. As the war progressed, artists also amplified opposition to the ongoing conflict as a theme.42

Early songs focused on news of war and the draft. Lightnin’ Hopkins, born Sam Hopkins in Centerville in 1912, recorded extensively from the 1940s, typically playing blues in the style that came out of his native Texas, like Blind Lemon Jefferson. He often covered topical events, as discussed in Joe Specht’s recent article “War News Blues: Lightnin’ Hopkins, World War II, Korea, and Vietnam” in the Journal of Texas Music History.43 In the song “War Is Starting Again” (Vee-Jay 1044, 1962), the narrator expresses fear of the coming conflict: “Well, I got news this morning/Right now they need a million men;” and reluctance to go: “I been overseas once/Oh, Lightnin' don't want to go there again.”

Luke Miles, who moved from Louisiana to Houston in the 1950s, also released "War Time Blues" (Smash S-1755, 1962), which addressed the war’s escalation under JFK and reluctance to be drafted: “When I get my examination [draft] card/I want the doctor to tell me I'm too doggone old.” Piano blues artist Teddy Reynolds, born in 1931 in Houston, grew up in the city’s racially segregated Third Ward and joined the house band of the neighborhood’s well-known blues nightclub Shady's Playhouse.44 In his song “I Thought the War Was Over” (Crown CLP 5245) (1962) the narrator refers to the “last war” (which could have been World War II or the Korean War), and that “Mr. K [Kennedy] said that don't mean a thing.” In a resigned fashion, the narrator accepts that “this world is all mixed up,” and that he will be returning to the “old war plant.” Texas blues harmonicist Billy Bizor, also born in the Centerville area, collaborated with Lightnin’ Hopkins on the track “Vietnam War” (Home Cooking LP 111, 1968) which took the perspective of a mother: “What if Uncle Sam were to call you?/ Boy, I would miss you so much I may die.”45

Once again, President Johnson became a focus of attention, with blues artists across the country addressing the Texan president. Myrtis Hardeman, a blind blues gospel artist based in Georgia, argued in “Speak to Vietnam” b/w “Mercy on Saigon” (National 45-007, ND) that “President Johnson…working for peace everywhere he goes” will “bring peace over in Vietnam.” But with the growing tensions in the Civil Rights movement, blues artists provided a less favorable view of LBJ. This became a significant theme, as sung by Mississippi-born J.B. Lenoir on his tour through Europe in 1965: “Mr. President, if you don't want to give us our Civil Rights, why do you send us to fight?” in his song “Everybody Crying About Vietnam” (Scout SC-1, 1968). This issue had been publicised widely in 1967 by Civil Rights leader Martin Luther King Jr., who delivered his speech “Why I Oppose the War in Vietnam” (Black Forum BF-451), which noted the “cruel irony of watching Negro and white boys on TV screens as they kill and die together for a nation that has been unable to seat them together in the same school room.”46

The public and political turn against the war from 1968 onwards was reflected in Texas blues. T-Bone Walker, born Aaron Thibeaux Walker in 1910 in Linden, took an anti-war soldier’s position in “Vietnam” (BluesTime BTS-9004, 1969): “I'm still in Vietnam… I just want this war to stop.” Walker calls the politicians “insane” and pleads with the “president and Congress” to stop the war. Lightnin’ Hopkins declares in “Please Settle in Viet Nam” (Joliet 205, 1969) that he wants to see “an ending to the war.” Both records were released during the Nixon presidency. In 1970, the more obscure blues artist Guitar Slim Green, born in 1907 in Bryan, released “This War Ain't Right” (Kent KST-549), depicting the war as a “lowdown dirty shame” and noting “I've got to go kill a brown man for the white man.”

Blues has often been overlooked in general overviews of Vietnam War-era political songs, which usually cite the familiar contemporary folk and rock tunes. But blues artists were in fact pioneers of the topical song, which through lengthy political discographies, provided a sense of historical context from World War II to Korea, and offering a more nuanced portrait of the US during the Vietnam era.

Soul, Gospel, & Funk: “Jody got your girl and gone”

Nearly 400 songs in the genres of soul, gospel, and funk addressed the Vietnam War across the US, and Texas played a central role with a flourishing Southern soul and gospel scene in Houston and across the state.

A number of these Texas songs involved influential record industry figures. Notorious Louisiana-born record producer and label owner Huey P. Meaux grew up in Winnie near Port Arthur and worked with the famous Houston-based SugarHill Studios in addition to being the founder or owner of no less than 15 record labels, nearly all based in Conroe or Houston.47 Houston DJ Skipper Lee Frazier, born in Magnolia Springs, Texas, in 1927, played a key role, managing and producing a number of prominent artists such as Archie Bell & the Drells. He also owned the record label Ovide and shared soul music through his radio programs.48 Meanwhile Don Robey, born in Houston in 1903, owned famous music venue the Bronze Peacock Dinner Club and multiple prominent labels, including Peacock and Songbird, with renowned artists like Willie Mae “Big Mama” Thornton.49

Early references to war in these genres from 1960 to 1966 often presented the “soldier boy” theme, in which a woman back in the US or a soldier fighting abroad misses their partner. These often contained a degree of patriotic sentiment, showing loyalty to the country, or just doing their legal duty by answering the draft call. Joe Tex, the Southern soul artist born Joseph Arrington Jr. in 1936 in Rogers, Texas, released a number of Vietnam War-related singles, including “I Believe I'm Gonna Make It” (Dial 4033, 1966), in which a soldier received a letter from the home front which gave him inspiration to fight and win: "I got your letter baby… I raised up and got two more enemies.” In the spoken-word verse, the narrator expresses disappointment that he did not marry his girlfriend "before I left for Vietnam.”

Christmas was a popular topic in songs from the soldier’s perspective. Houston-based gospel group the Soul Searchers released “Christmas in Viet Nam” (Songbird 1187, 1967) on a Don Robey label, in which “a lonely soldier lay dying in a foxhole in Vietnam” thinking of home. Dan Henderson, an obscure soul artist from San Antonio, released the rare single “Dear Son” (Dynamic 119, ND) which took the letter format: “I’m not at home for Christmas;” “You must be brave my son… Maybe when you’re all grown up, there’ll never be war.” The Masters of Houston were managed by Skipper Lee Frazier and recorded for his record label Ovide.50 In the song “Please Wait for Me (My Darling)” (Ovide 232, ND), a soldier explains, “The odds on my returning they say are a million to one,” but he urges his lover, “Darling, please hold on.”

A prominent sub-theme of these relationship songs was the “Jody” song. “Jody” was the mythical man “Joe the Grinder” found in blues, jazz, and soul tunes since the 1940s who seduced the wives and girlfriends of soldiers, prisoners, and those away from home. “Grinder” is an old slang word for sex (dated circa 1647). During World War II, African Americans introduced the theme into the army in military cadences with the phrase “Ain’t no use in going home, Jody’s got your girl and gone,” shouted out by a military officer, and repeated by the group of marching soldiers in unison. This type of march got the nickname of “jodies” or “jody calls.”51

One of the earliest of the “Jody” soul songs out of Texas in the Vietnam era came from Joe Medwick, born in 1931 in Houston’s Third Ward. After serving in the US military in the Korean War, he became an established figure at Shady’s Playhouse alongside Texas blues artists such as Teddy Reynolds.52 In his novelty narration “Letter to a Buddie” (Boogaloo 1002, 1967), produced and co-written by Huey Meaux, a man tells his friend, “I sure do envy you over there in Vietnam,” while describing how his wife Sally was spending all her time with a man named Clive, “wearing your old smoking jacket” and “rooming in the house now.”53 Joe Tex’s “(When Johnny Comes Marching Home) I Can't See You No More” (Dial 4095, 1969) is narrated from the perspective of the “Jody,” noting that the woman he is having an affair with “is waiting on a man, right now, he is in the army.” The perspective of the “Jody” is also found in Lightnin’ Hopkins’s “War Is Starting Again.” The narrator says, “You know my girlfriend got a boyfriend in the army, that fool better go overseas.” Likewise, in Hopkins’s “Please Settle in Viet Nam,” he notes, “My girlfriend got a boyfriend fighting… I hope he'll stay forever.”

One of the most commercially successful “Jody” soul songs came from Johnnie Taylor, who was born in Arkansas in 1937 but spent most of his life and career in Texas, which included joining the famous Texas gospel group the Soul Stirrers, replacing Sam Cooke as its lead singer in 1956.54 In “Jody Got Your Girl and Gone” (Stax STA-0085, 1970) the narrator warns the soldiers that “there's a cat named Jody…in every town,” concluding that there “ain't no sense in going home.” The song reached number one in the Billboard R&B charts on February 20, 1971 and peaked at number 28 on the Billboard Hot 100 on February 27.55 Meanwhile, in another interesting take on the relationship song, Johnnie Taylor, in his “I Could Never Be President” (Stax STA-0046, 1969), declared that if elected to the White House, he would “bring home all the fellows from over in Vietnam” in order to redeploy them to protect his sweetheart from the world. While not a song specifically about the war, it reflected the prominence of the issue in popular culture.

An alternative take on relationships, rarely seen in Vietnam War songs, came from Gloria Edwards, from Houston, in “Something You Couldn't Write About,” on Huey Meaux's label Jet Stream (814, 1971). The song describes a US soldier who had an affair with a Vietnamese woman, producing a child. The soldier’s wife “found that picture” of the Vietnamese woman and the soldier “holding that darling boy.” The song ends on an ominous note: “For you the war is over” but “for me it has just begun.”

Prominent Houston-based soul/R&B group Archie Bell & the Drells presented a perspective of reluctance to the draft and a lack of eagerness to go to war, rather than politically for or against, in the song “A Soldier's Prayer 1967” on Skipper Lee Frazier’s label (Ovide 226). The narrator received the draft card “to go to Vietnam” and cried out: “please Uncle Sam I really don't want to go.” According to multiple accounts, the leader singer, Archie Bell, was drafted to fight in the Vietnam War on May 12, 1967, and his band member Billy Butler tried to cheer him up with an impromptu version of a demo they recorded in 1964 called “Tighten Up,” which became the title of their famous 1968 album (Atlantic SC 8181). Bell was wounded in Vietnam, and while recovering in a Veterans Administration hospital, the song “Tighten Up” hit number one on the Billboard charts on April 13, 1968.56

Formed in Dallas in 1958, the Masquerades’ touch on a similar theme in “Let’s Face Facts” (Wand WND 1168, 1967), in which the narrator, a soldier, says that he “don't wanna go.” While wishing for his partner to “be strong,” he hopes that “pretty soon this war is gonna be over.” Tiny Watkins, a soul artist from Alabama, pleaded directly to the Texan president” in “Soldier's Sad Story” (Excello 2287, 1967): “LBJ, I know you mean to do goo… help me if you can” because “I don't want to lose my baby.” Jazz-soul artist Bus Brown was more confident in the president’s abilities in “Mr. L.B.J.” (Burman B0001, 1966): “Mr. LBJ, everything you’re doing is right for the USA… I know you can take care of Vietnam.”

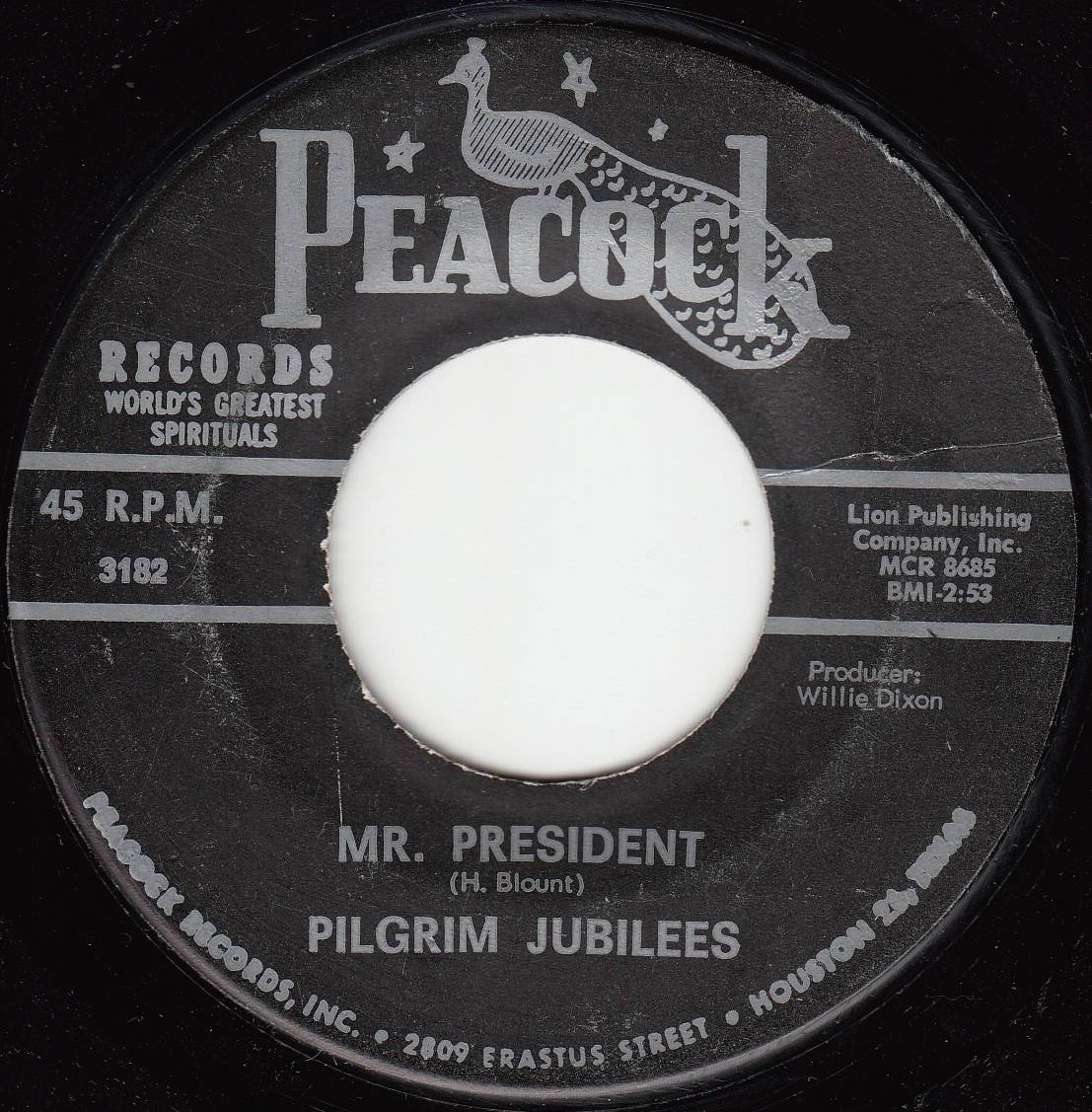

While a significant proportion of soul, gospel, and funk songs in the early part of the conflict focused on the draft and relationships, a rare exception from 1961 was a gospel song by the Pilgrim Jubilees, from Houston on Don Robey’s Peacok label. The song takes an early anti-war perspective, noting in “Mr. President” (Peacock 3182) the First and Second World Wars, Korea, and the current “rumours of war.” The song questions the point of the new conflict developing in Vietnam: “Why should our boys lose their lives away from home?”

Houston-based Ramona Jones saw the war effort as a general failure in society and world affairs in the soul song “(We Break) The Rules Made for Man,” released on a Meaux label (Jet Stream 801, 1970). Jones notes, “No wonder we've been fighting over there in Vietnam” as there was “no brotherly love.” Likewise, funk group the Rock called for peace in “(Charlie, Brother) We Got to Love One Another” (Scorpio S-101, 1971), a single on Don Robey’s Duke Records. Jones compares the violence at home and abroad: “Stop your wholesale killing… Stop the ghetto robbing.”

The more than 500 songs by African American artists about the Vietnam War in the genres of blues, soul, gospel, and funk have rarely been analysed in cultural literature on the war, overlooked in favor of patriotic country songs or contemporary folk & rock protest, predominantly by white artists. According to the Library of Congress, approximately 300,000 African Americans served in the Vietnam War, of which 7,241 died. Looking at a single year, in 1965, African Americans comprised 31% of combat troops, while only covering 12% of the general US population—that year, African Americans suffered 24% of US army casualties. This trend continued throughout the war, and the casualty rate of African Americans remained significantly disproportionate.57 African Americans fought for their country and had more rights and equality in the army than in the US where segregation persisted, which encouraged a large cultural output of political and war-related material. Studying these songs provides a more accurate and complete look at the Vietnam War era and its impact on America.58

Tejano music: "It is my pride to be Texan and Texan Mexican"

Probably the most overlooked topic in Vietnam War song literature is Mexican American songs, with over 150 identified by the VWSP. Most came from Texas (broadly classed as “Tejano”), but also from the border states New Mexico, Arizona, and California with a hybrid of Mexican and US influences, including traditional genres such as conjunto, norteño, ranchera, and corrido, usually recorded in Spanish. These songs contribute to a better understanding of how the war was perceived in different cultural and music scenes across the US, with Texas playing a central role.59

On September 8, 1973, Billboard ran the piece “Tex-Mex Sounds Undergo Changes: Rio Grande Valley a Hot Spot” as part of a spotlight on Texas, which reported, “Texas’ Rio Grande Valley has probably done more to help the growth of Chicano music than almost any other single area,” especially in the “the small Texas city of McAllen.” It went on to note that “although some young Chicano citizens no longer speak Spanish…the pride of the Mexican culture is embedded deeply in the citizens of Texas and…their music will never die.”60

In addition, vast numbers of Latino US citizens served in the military. Over 80,000 Latinos served in the Vietnam War, making up 5.5% of deaths while only consisting of 4.5% of the US population.61 Billboard also noted the large number of Texan Latinos fighting in the war in a profile of Tex-Mex music: “[M]ore military personnel with Mexican American surnames have been killed and wounded in Viet Nam than any other group in the state of Texas.”62 With a substantial military culture and its vibrant music scenes, it is not surprising that many Mexican American records came out of Texas with war-related themes.

One of the leaders of this growing Mexican American music movement out of McAllen was Arnoldo Ramirez, born in Mission on April 9, 1918. Ramirez founded and owned multiple prominent Mexican American labels based in McAllen, including Falcon, ARV International, Bego, Bronco, and Impacto. Together, they released thousands of records, many of which dealt with political topics from Vietnam to the assassinations of JFK, MLK, and RFK. This included an entire war-themed artist compilation: Porque estamos en Vietnam (Why We Are in Vietnam) (Bronco BRLP-043, ND), that showcased prominent Texas-based Mexican American artists. The title track was taken from Arnoldo Ramirez’s spoken-word single (Falcon 1724) defending the war’s objectives. Like Texas country music, most Mexican American songs during the war years leaned towards the patriotic category. But as in all genres, songs displayed a wide variety of themes and political views that altered throughout various stages of the war.

The most recognisable pattern in the overall patriotic category of Mexican American songs was a focus on the soldier through the corrido—songs that traditionally spread news in Mexican territories through folk music since the 19th century. Musicians continued this tradition in the US, singing about wars and political events. Agapito Zúñiga, born in Mexico in 1924, immigrated to the US and lived in Corpus Christi where he released “Corrido de Jimmy Aguirre” (Escorpión 114, 1969) about a Mexican American soldier who was killed in action and won the Distinguished Service Cross for saving five members of his platoon. Moreover, the song notes his Mexican heritage: “Jimmy threw himself into combat, and his name asserted/He was Mexican, to die or to win.”63 This topic also appears in “Corrido de Pancho Alvarez” (Canasta 1038, ND) by the group Los Fabulosos Robles de Reynosa, released in Kingsville, about a Rio Grande City-born draftee killed in Vietnam on November 25, 1968.64

Of the Vietnam War corrido, the most well-known was about Daniel Fernandez, the subject of at least four songs identified to date.65 Fernandez was the first Mexican American soldier awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor for service in Vietnam, with the citation noting his “patrol was ambushed by…Viet Cong” and Fernandez “threw himself on the grenade as it exploded, saving the lives of his 4 comrades at the sacrifice of his life.”66 In the song “Corrido de Daniel Fernandez” (Del Valle 830, ND) by Los Reyes de la Frontera, released in McAllen and composed by New Mexico-based Roberto Martinez, the narrator explains that Fernandez was a “valiant soldier” who died "because of the love of his homeland.”67

In addition to the pro-soldier songs, anti-communism and pro-US government policy sentiment crept into the lyrics. Bobby Flores, a child performer out of San Antonio, recorded “M.I.A. Missing in Action” (Joey 5003, ND), narrated from the perspective of a son whose father was missing in Vietnam and who argued he was there “to preserve the right of freedom for people.” In the song “Ya volvi de Vietnam” (“I Just Got Back From Vietnam”) (Corona 2392, ND) by Jimmy Jimenez, released in San Antonio, the narrator had been “fighting against those red traitors.”68 The song was covered by at least three other artists.

Trio Totonacas recorded “Mexicanos en Vietnam” (Del Centro DC 5041, ND), a Spanish-language ranchera track that focused on cultural identity and nationality, including being both Mexican American and from Texas, and continuing a link to their Mexican cultural heritage: “I am Mexican… I was born abroad… It is my pride to be Texan and Texan Mexican.” The song contains patriotic sentiment, referencing US involvement in World War II and Korea: “In the war in Germany we offered our lives” and “in Korea we tested it,” which sought to connect the ongoing struggle of the US to fight justified wars. The narrator concludes, “We continue together with the war in Vietnam.”69 Highlighting Mexican heritage in songs centred around patriotism for the US sought to showcase loyalty from the community.

In the pivotal year of 1968, one of the most prominent Texas groups, Little Joe and the Latinaires, led by José María De León Hernández (“Little Joe”), born in 1940 in Temple, released "A la guerra ya me llevan" on his own record label out of Temple (Buena Suerte 929, 1968). The song is primarily narrated from the perspective of a soldier who misses his family and expresses a reluctance to go to war: “They're taking me against my will.” Likewise, George Jay released the Mexican American soul track “Greetings (This Is Uncle Sam)” (ARV A-5012, 1968) out of McAllen, a cover of the Valadiers (Miracle MI-6, 1961) and the Monitors (VIP 25032, 1966) (both recorded for Motown subsidiaries), in which a soldier reluctantly answers the draft call: “Oh no, you're in the army now…to fight in Vietnam.” Eddie Aleman, in “Soldadito” (Omega 1004, ND), tread a careful line, with a special note on the picture sleeve, praising “those fighting men” but also noting “that war is hell.” Other groups took a more direct approach. The Royal Jesters, also known as the Jesters, from San Antonio called out, “People get ready, a change is gonna come” in the track “Sing a Song of Peace” (Optimum B-595, 1972).

Another form of protest involved the issue of Mexican American civil rights, as displayed in multiple songs about Mexican American soldier Richard Campos, including "El soldado huerfanito (Homenaje al Sgt. Richard Campos)" ("The Orphan Soldier") (Norteño 266, ND), by Los Conquistadores, released in San Antonio. Campos was killed in action in Vietnam at the age of 26 in 1966, and his body was shipped to the US but lay unclaimed at an army airbase in California for more than ten days. Campos was an orphan with no known family and had been a ward of the court when he joined the army in 1958. After the story came to light, offers came from across the US to bury the soldier.70 However, the most prominent version of the song, composed by Daniel Valdez (Cucaracha 1447, ND), argued that the body was left abandoned because of his color: “In a terminal in Oakland lies the brown body of a man, dead at 27/Dead and gone to heaven, killed far away in Vietnam.” The song was later covered by well-known contemporary folk artist Barbara Dane as “The Ballad of Richard Campos” on her protest album FTA!: Songs of the GI Resistance (Paredon 1003, 1970), featuring active duty GIs, with several of the songs recorded at Fort Hood.

Dozens of other Mexican American songs from across Texas, including McAllen, El Paso, San Antonio, Austin, Houston, and Dallas, focused on the soldiers’ experiences of going off to war, in combat, and returning to the US. In “En el frente del Viet Nam” (“On the front in Vietnam”) (Del Sur DS-105, ND) by Pepe Maldonado on his Del Sur record label from Edinburg, the narrator highlights the fear of combat: “Enemy searches for me, they want to kill me/And I defend my life because I want to return.”71 Several corridos also paid tribute to Mexican American journalist Martin Rosales, born in 1929 in Gonzales, who reported from Vietnam in 1968, as the South Vietnam Spanish language correspondent on behalf of KGBT-TV in Harlingen, which offered a look at a different type of role in the conflict.72 Meanwhile, multiple singles focused on the families left behind in the US, such as “El padre de un soldado” (“The Father of a Soldier”) (Gapoca 252, ND) released by Shorty Martinez in Houston, in which a father prays to god to “protect all the soldiers that find themselves in Vietnam.”73 Similarly, in Poncho Villagómez’s “Imploracion de un padre” the narrator prays to god because a “son of mine, he is fighting in Vietnam . . . My home is not complete” (Del Rio DDR-023, ND). As with the African American community, a significant and disproportionate number of Mexican American citizens fought and died in the conflict, while back home they faced their own battle for equality and recognition of the military service they provided. Largely ignored in studies of the Vietnam War, the more than 150 Latino songs referencing the conflict from across the US, most of which came out of Texas, provide a more accurate picture of the era.

Post-War: "You were an American...whose innocence was lost"

Almost half of the more than 6,000 Vietnam War songs I have identified with the Vietnam War Songs Project were released in the post-war period. They focus on veteran-related issues such as disabilities, mistreatment, economic struggles, reflections on the long-term impact of the war, and using Vietnam as a comparison point to other world events and wars.

The first wave of songs appeared between the 1973 peace agreement and the 1975 fall of Saigon, with many focused on the returning American GIs and the POWs, and, being so close to the war, continuing the dove versus hawk divide. Fort Worth country artist David L. Cash stated such a sentiment in the title of his single “We Are Glad That Our Boys Are Coming Home.” (Stargo SG-13, 1973). Cash welcomes a lasting peace following the release of POWs, praises the returning soldiers, and notes how some had suffered disabilities.

Artists and songwriters narrated dozens of songs from the perspective of the veteran. Country legend George Jones, born in 1931 in Saratoga, Texas, although largely based in Nashville, released “The Door” (Epic 8-50038, 1971) about a break-up in which a veteran also recalls the sounds of war: “The sound of the train that took me off to war/The awful sound of a thousand bombs exploding.” It placed number one in the US Billboard country chart and spent 10 weeks in the charts. Meanwhile, Houston-based soul artist Leo Price recorded “I’ve Been a Prisoner” (Faces 3-1, 1973) about a POW recently returned home who had “been looking for my sweetheart ever since I arrived.” He even somewhat over-optimistically provided his location in the song, hoping she would hear it: “Holiday Inn, number 700, block off the East Texas freeway.”

Phil Ochs kept up his criticism of the government, focusing on Nixon, Watergate, and the war in “Here’s to the State of Richard Nixon” (A&M 1509, 1974) where “The wars are fought in secret… And criminals are posing as advisors,” a re-working of his famous civil rights song “Here’s to the State of Mississippi” (Elektra EKS 7287, 1965). Avant-garde free jazz artist Marvin "Hannibal" Peterson, born in 1948 in Smithville, and currently based in Bastrop, released Children of the Fire (Sunrise 1944, 1974), which came with an insert that stated, “Dedicated to the Children of Vietnam.” Outlaw country artist Ray Wylie Hubbard wrote the classic “Up Against the Wall, Redneck Mother” (1973), a country music parody answering Merle Haggard’s patriotic wartime hit “Okie from Muskogee,” which at times has become divorced from its Vietnam context in public memory (Capitol 2626, 1969). Mexican American psychedelic rock group El Gusano released the album Fantasia del Barrio (Joey 2016, 1975), recorded in San Antonio. Lead singer Eugenio Jaimez, a Vietnam veteran based in Laredo, described it as a “remembrance of a hellish war that many of our brothers met with by chance.”74